- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

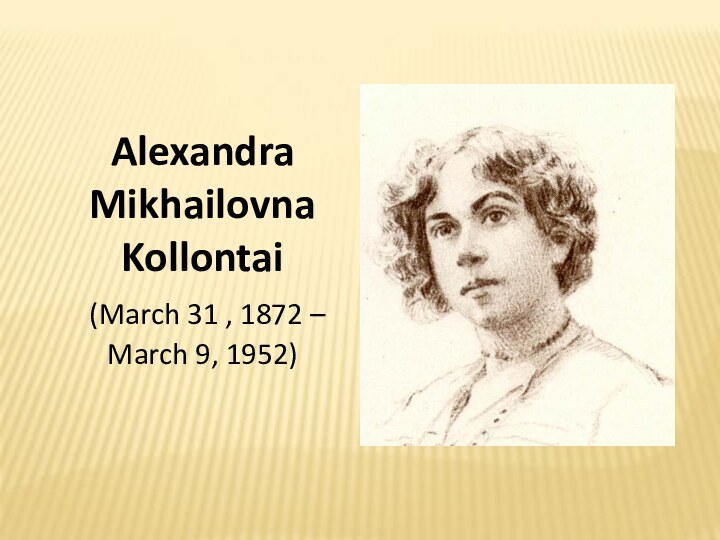

Презентация на тему Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai

Содержание

- 2. Aleksandra Mikhaylovna Kollontai was a Russian revolutionary, feminist and the first Soviet female diplomat

- 3. Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich was born on March

- 5. Alexandra

- 6. In 1890 or 1891,

- 7. She became a

- 8. In 1904,

- 9. Between 1900 and

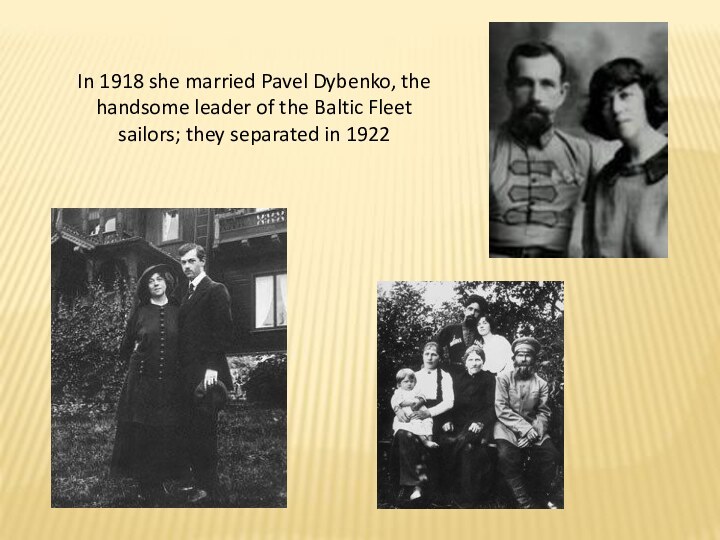

- 10. In 1918 she married Pavel Dybenko, the

- 11. She visited

- 12. Kollontai joined the

- 13. This included periods in Norway (1923-25), (1927-30)

- 14. Mexico (1925-27)1926: Witt Mexico President Elias Calles

- 15. After several ministerial

- 16. Kollantai retired in

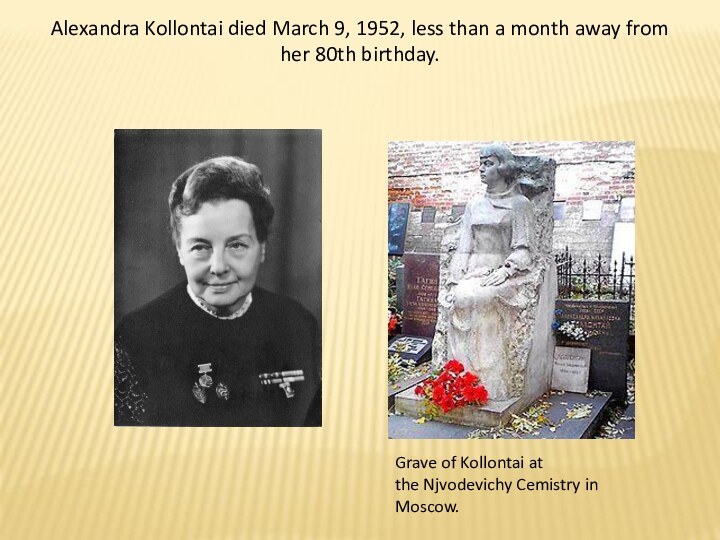

- 17. Alexandra Kollontai died March 9, 1952, less

- 18. Скачать презентацию

- 19. Похожие презентации

Aleksandra Mikhaylovna Kollontai was a Russian revolutionary, feminist and the first Soviet female diplomat

Слайд 2 Aleksandra Mikhaylovna Kollontai was a Russian revolutionary, feminist

and the first Soviet female diplomat

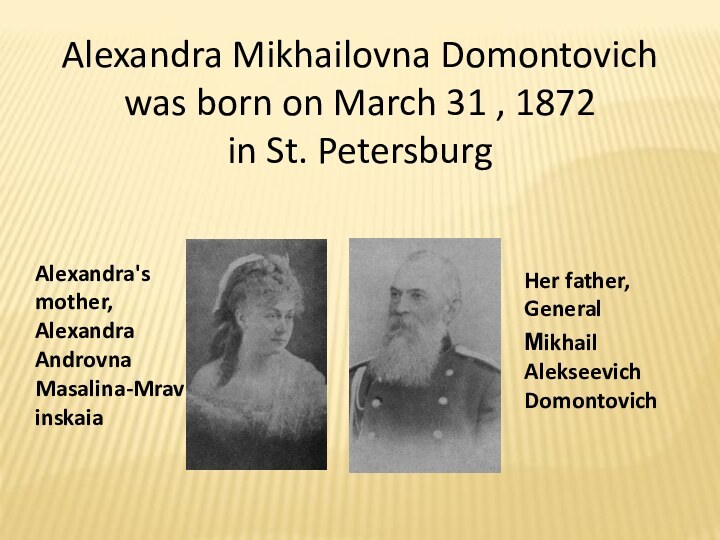

Слайд 3 Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich was born on March 31 , 1872

in St. Petersburg

Alexandra's mother, Alexandra Androvna Masalina-Mravinskaia

Her father, General

Мikhail Alekseevich

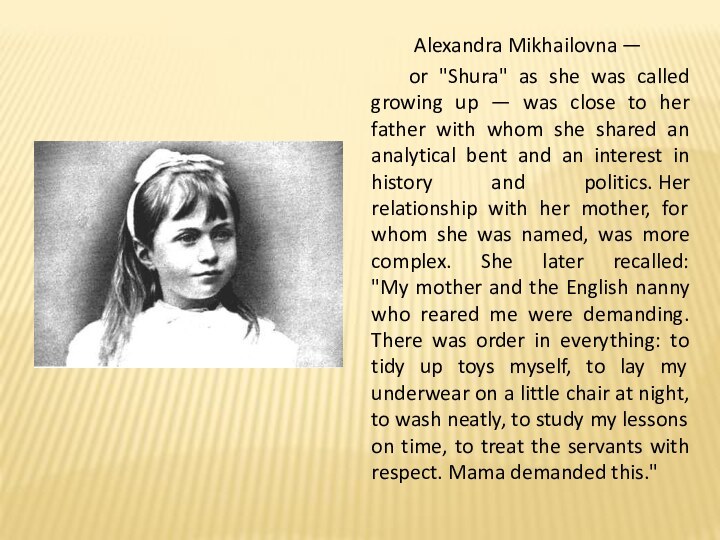

DomontovichСлайд 4 Alexandra

Mikhailovna —

or "Shura" as she

was called growing up — was close to her father with whom she shared an analytical bent and an interest in history and politics. Her relationship with her mother, for whom she was named, was more complex. She later recalled:

"My mother and the English nanny who reared me were demanding. There was order in everything: to tidy up toys myself, to lay my underwear on a little chair at night, to wash neatly, to study my lessons on time, to treat the servants with respect. Mama demanded this."Слайд 5 Alexandra was

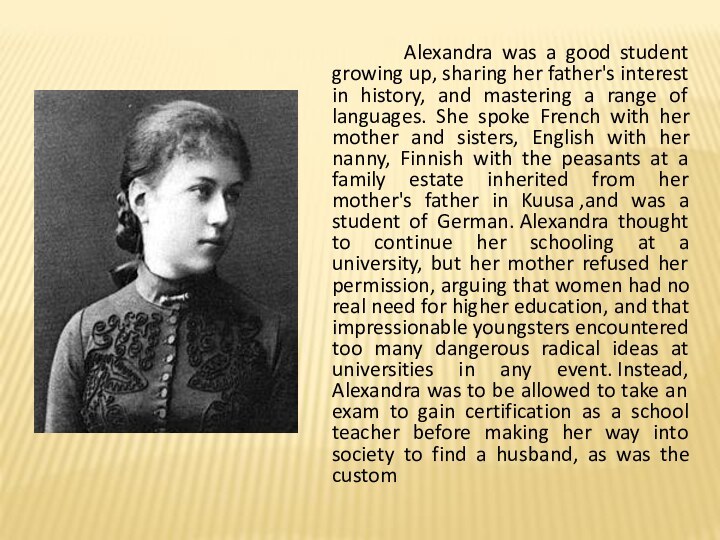

a good student growing up, sharing her father's interest

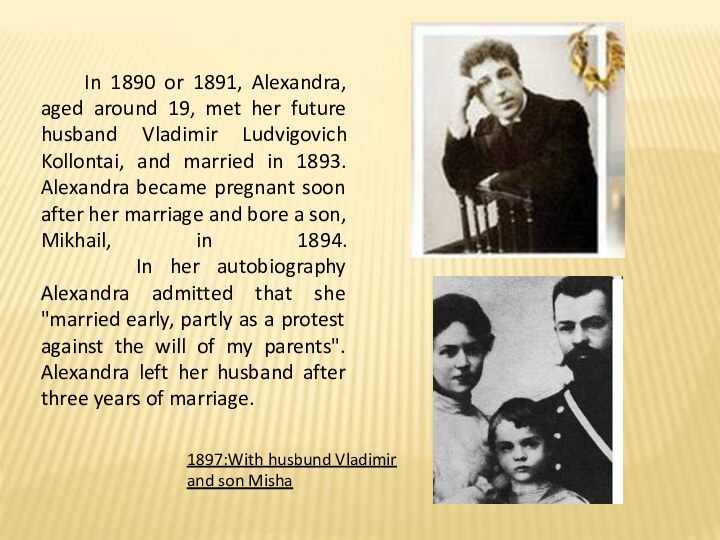

in history, and mastering a range of languages. She spoke French with her mother and sisters, English with her nanny, Finnish with the peasants at a family estate inherited from her mother's father in Kuusa ,and was a student of German. Alexandra thought to continue her schooling at a university, but her mother refused her permission, arguing that women had no real need for higher education, and that impressionable youngsters encountered too many dangerous radical ideas at universities in any event. Instead, Alexandra was to be allowed to take an exam to gain certification as a school teacher before making her way into society to find a husband, as was the customСлайд 6 In 1890 or 1891, Alexandra,

aged around 19, met her future husband Vladimir Ludvigovich

Kollontai, and married in 1893. Alexandra became pregnant soon after her marriage and bore a son, Mikhail, in 1894. In her autobiography Alexandra admitted that she "married early, partly as a protest against the will of my parents". Alexandra left her husband after three years of marriage.1897:With husbund Vladimir

and son Misha

Слайд 7 She became a member

of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, aged 27,

in 1899. She was a witness of the popular rising in 1905 known as Bloody Sunday, at Saint Petersburg in front of the Winter Palace.1905: Potrait of Kollontai

Слайд 8

In 1904, she

joined the Bolshevik faction and conducted classes on Marxism

for it. In 1905, she joined with Leon Trotsky in pressing for a more positive attitude toward the newly-emerged Soviets and in pressing for unity of the party factions. She became treasurer of the St. Petersburg Social Democratic Committee.Слайд 9 Between 1900 and 1917

Kollontai participated in the revolutionary underground in Russia, but

mostly she lived abroad, where she made her reputation as a theoretician of Marxist feminism.In the prerevolutionary period Kollontai also became known as a skilled journalist and orator. She was aMenshevik, but in 1913, when Bolsheviks Konkordia Samoilova, Inessa Armand, and Nadezhda Krupskaya launched a newspaper aimed at working-class women, they invited Kollontai to be a contributor. She responded enthusiastically.