- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Шекспир

Содержание

- 3. Early life William Shakespeare was

- 4. Classification of the plays

- 6. In the late nineteenth century, Edward Dowden

- 7. Works

- 8. Comedies Main article: Shakespearean comedyAll's Well That

- 9. Histories Main article: Shakespearean historyKing John Richard

- 10. Tragedies Main article: Shakespearean tragedyRomeo and Juliet

- 11. Poems Shakespeare's Sonnets Venus and Adonis The

- 12. Lost plays Love's Labour's Won Cardenio

- 13. Apocrypha Main article: Shakespeare ApocryphaArden of Faversham

- 14. Published in 1609, the Sonnets were the

- 15. Sonnet 02 When forty winters shall besiege

- 16. Sonnet 22 My glass shall not persuade

- 17. Sonnet 130 My mistress' eyes are nothing

- 18. Sonnet 121 'Tis better to be vile

- 19. Скачать презентацию

- 20. Похожие презентации

William Shakespeare (baptised 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an an English poet

![Шекспир Tragedies Main article: Shakespearean tragedyRomeo and Juliet Coriolanus Titus Andronicus†[h] Timon of](/img/tmb/13/1271410/f6178366601de5c8a462264acbba757d-720x.jpg)

Слайд 3 Early life William Shakespeare was the son of John

Shakespeare, a successful glover and alderman originally from Snitterfield

and Mary Arden, the daughter of an affluent landowning farmer. He was born in Stratford-upon-Avon and baptised on 26 April 1564. His unknown birthday is traditionally observed on 23 April, StGeorge's Day.This date, which can be traced back to an eighteenth-century scholar's mistake, has proved appealing because Shakespeare died on 23 April 1616. He was the third child of eight and the eldest surviving son. Although no attendance records for the period survive, most biographers agree that Shakespeare was educated at the King's New School in Stratford, a free school chartered in 1553, about a quarter of a mile from his home. Grammar schools varied in quality during the Elizabethan era, but the curriculum was dictated by law throughout England, and the school would have provided an intensive education in Latin grammar and the classics.Слайд 5 Shakespeare's works include the 36 plays printed in

the First Folio of 1623, listed below according to

their folio classification as comedies, histories and tragedies. Shakespeare did not write every word of the plays attributed to him; and several show signs of collaboration, a common practice at the time. Two plays not included in the First Folio, The Two Noble Kinsmen and Pericles, Prince of Tyre, are now accepted as part of the canon, with scholars agreed that Shakespeare made a major contribution to their composition. No poems were included in the First Folio.

Слайд 6

In the late nineteenth century, Edward Dowden classified

four of the late comedies as romances, and though

many scholars prefer to call them tragicomedies, his term is often used. These plays and the associated Two Noble Kinsmen are marked with an asterisk (*) below. In 1896, Frederick S. Boas coined the term "problem plays" to describe four plays: All's Well That Ends Well, Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida and Hamlet. "Dramas as singular in theme and temper cannot be strictly called comedies or tragedies", he wrote. "We may therefore borrow a convenient phrase from the theatre of today and class them together as Shakespeare's problem plays."The term, much debated and sometimes applied to other plays, remains in use, though Hamlet is definitively classed as a tragedy. The other problem plays are marked below with a double dagger (‡).Plays thought to be only partly written by Shakespeare are marked with a dagger (†) below. Other works occasionally attributed to him are listed as lost plays or apocrypha

Слайд 8

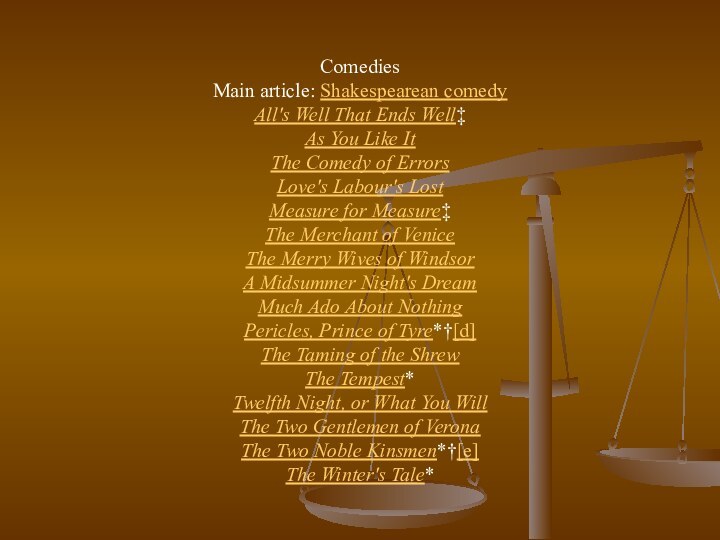

Comedies

Main article: Shakespearean comedy

All's Well That Ends

Well‡

As You Like It

The Comedy of Errors

Love's Labour's Lost

Measure for Measure‡

The Merchant of Venice

The Merry Wives of Windsor

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Much Ado About Nothing

Pericles, Prince of Tyre*†[d]

The Taming of the Shrew

The Tempest*

Twelfth Night, or What You Will

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

The Two Noble Kinsmen*†[e]

The Winter's Tale*

Слайд 9

Histories

Main article: Shakespearean history

King John

Richard II

Henry IV, part 1

Henry IV, part 2

Henry

V Henry VI, part 1† [f]

Henry VI, part 2

Henry VI, part 3

Richard III

Henry VIII†[g]

Слайд 10

Tragedies

Main article: Shakespearean tragedy

Romeo and Juliet

Coriolanus

Titus Andronicus†[h]

Timon of Athens†[i]

Julius Caesar

Macbeth† [j]

Hamlet

Troilus and Cressida‡

King Lear

Othello

Antony and Cleopatra

Cymbeline*

Слайд 11

Poems

Shakespeare's Sonnets

Venus and Adonis

The Rape

of Lucrece

The Passionate Pilgrim[k]

The Phoenix and the

Turtle A Lover's Complaint

Слайд 13

Apocrypha

Main article: Shakespeare Apocrypha

Arden of Faversham

The

Birth of Merlin

Locrine

The London Prodigal

The Puritan

The Second Maiden's Tragedy

Sir John Oldcastle

Thomas Lord Cromwell

A Yorkshire Tragedy

Edward III

Sir Thomas More

Слайд 14 Published in 1609, the Sonnets were the last

of Shakespeare's non-dramatic works to be printed. Scholars are

not certain when each of the 154 sonnets was composed, but evidence suggests that Shakespeare wrote sonnets throughout his career for a private readership. Even before the two unauthorised sonnets appeared in The Passionate Pilgrim in 1599, Francis Meres had referred in 1598 to Shakespeare's "sugred Sonnets among his private friends". Few analysts believe that the published collection follows Shakespeare's intended sequence. He seems to have planned two contrasting series: one about uncontrollable lust for a married woman of dark complexion (the "dark lady"), and one about conflicted love for a fair young man (the "fair youth"). It remains unclear if these figures represent real individuals, or if the authorial "I" who addresses them represents Shakespeare himself, though Wordsworth believed that with the sonnets "Shakespeare unlocked his heart". The 1609 edition was dedicated to a "Mr. W.H.", credited as "the only begetter" of the poems. It is not known whether this was written by Shakespeare himself or by the publisher, Thomas Thorpe, whose initials appear at the foot of the dedication page; nor is it known who Mr. W.H. was, despite numerous theories, or whether Shakespeare even authorised the publication. Critics praise the Sonnets as a profound meditation on the nature of love, sexual passion, procreation, death, and time.Sonnets