Слайд 2

Economic Growth

Economic growth is a long-term expansion of

the productive potential of the economy.

Growth is not the

same as development! Growth can support development but the two are distinct.

M. Todaro defines economic development as an increase in living standards, improvement in self-esteem needs and freedom from oppression as well as a greater choice.

Economic development is Concerned with structural changes in the economy, but economic growth is concerned only with increase in the economy’s output.

Economic growth is a necessary but not sufficient condition of economic development.

Economic growth brings quantitative changes in the economy; where as economic development deals with quantitative and qualitative changes in the economy.

Слайд 3

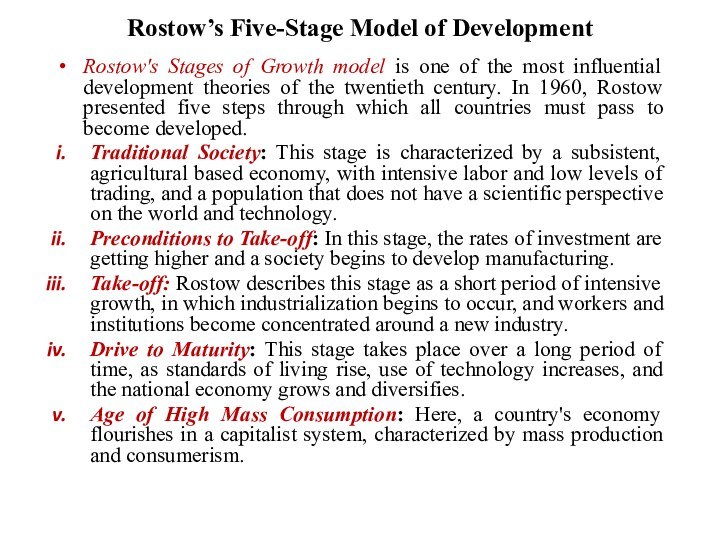

Rostow’s Five-Stage Model of Development

Rostow's Stages of Growth

model is one of the most influential development theories

of the twentieth century. In 1960, Rostow presented five steps through which all countries must pass to become developed.

Traditional Society: This stage is characterized by a subsistent, agricultural based economy, with intensive labor and low levels of trading, and a population that does not have a scientific perspective on the world and technology.

Preconditions to Take-off: In this stage, the rates of investment are getting higher and a society begins to develop manufacturing.

Take-off: Rostow describes this stage as a short period of intensive growth, in which industrialization begins to occur, and workers and institutions become concentrated around a new industry.

Drive to Maturity: This stage takes place over a long period of time, as standards of living rise, use of technology increases, and the national economy grows and diversifies.

Age of High Mass Consumption: Here, a country's economy flourishes in a capitalist system, characterized by mass production and consumerism.

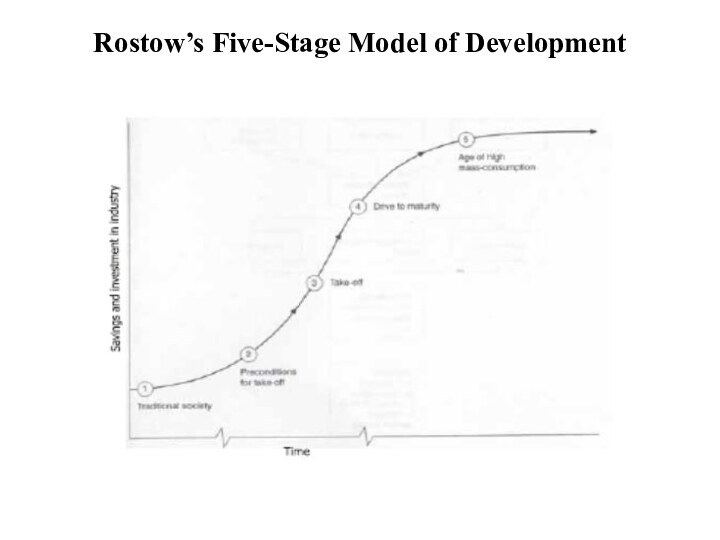

Слайд 4

Rostow’s Five-Stage Model of Development

Слайд 5

Modernization Theory

Linear stages of development

Слайд 6

Economic Growth

Growth rate

How rapidly real GDP per person

grew in the typical year.

Growth in GDP per capita

(or per worker) Y/L

Real GDP per person

Living standard

Vary widely from country to country

Because of differences in growth rates

Ranking of countries by income changes substantially over time

Слайд 7

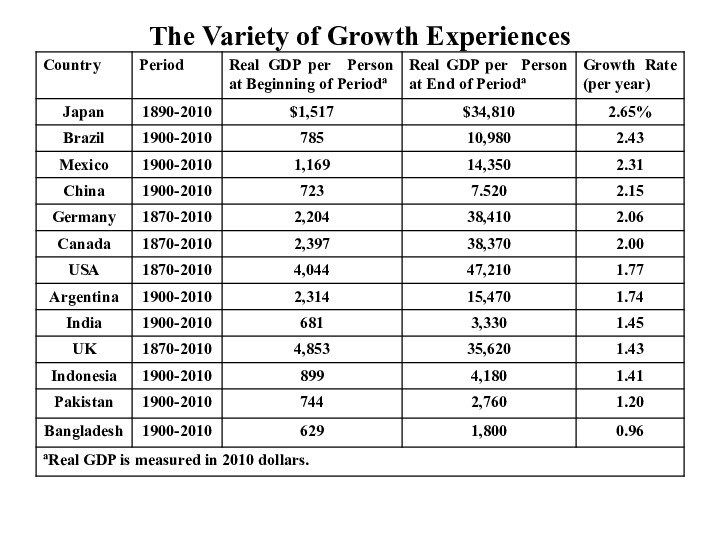

The Variety of Growth Experiences

Слайд 8

Productivity

Productivity

Quantity of goods and services

Produced from each unit

of labor input

Why productivity is so important

Key determinant of

living standards

Growth in productivity is the key determinant of growth in living standards

An economy’s income is the economy’s output

Слайд 9

Productivity

Determinants of productivity

Physical capital

Stock of equipment and

structures

Used to produce goods and services

Human capital

Knowledge and skills

that workers acquire through education, training, and experience

Слайд 10

Productivity

Determinants of productivity

Natural resources

Inputs into the production

of goods and services

Provided by nature, such as land,

rivers, and mineral deposits

Technological knowledge

Society’s understanding of the best ways to produce goods and services

Слайд 11

Additionally, other explanations have highlighted the significant role

of non-economic factors.

These include institutional economics which underlines the

substantial role of institutions, policy, legal and political systems (Matthews, 1986; North, 1990; Jutting, 2003)

Economic sociology stressed the importance of socio-cultural factors such as Confucianism in East Asia (Granovetter, 1985; Knack and Keefer, 1997).

Слайд 12

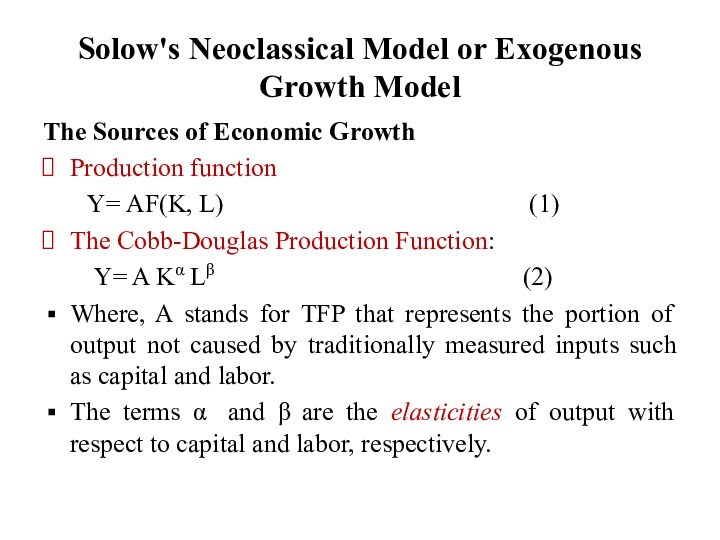

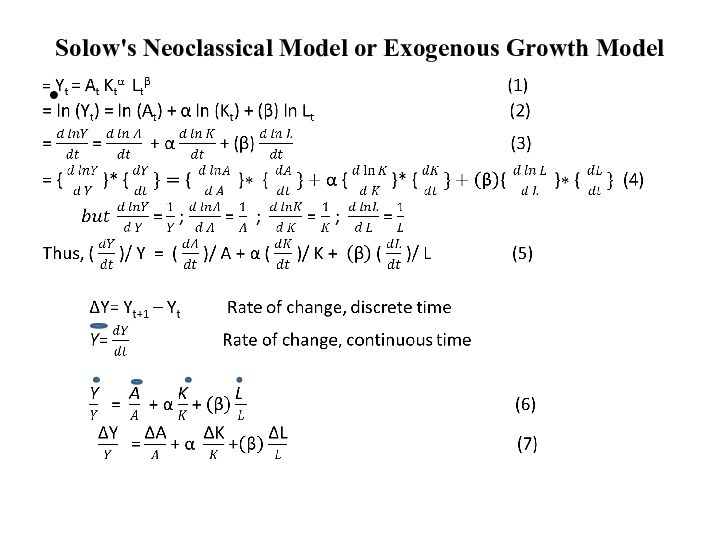

Solow's Neoclassical Model or Exogenous Growth Model

The Sources

of Economic Growth

Production function

Y=

AF(K, L) (1)

The Cobb-Douglas Production Function:

Y= A Kα Lβ (2)

Where, A stands for TFP that represents the portion of output not caused by traditionally measured inputs such as capital and labor.

The terms α and β are the elasticities of output with respect to capital and labor, respectively.

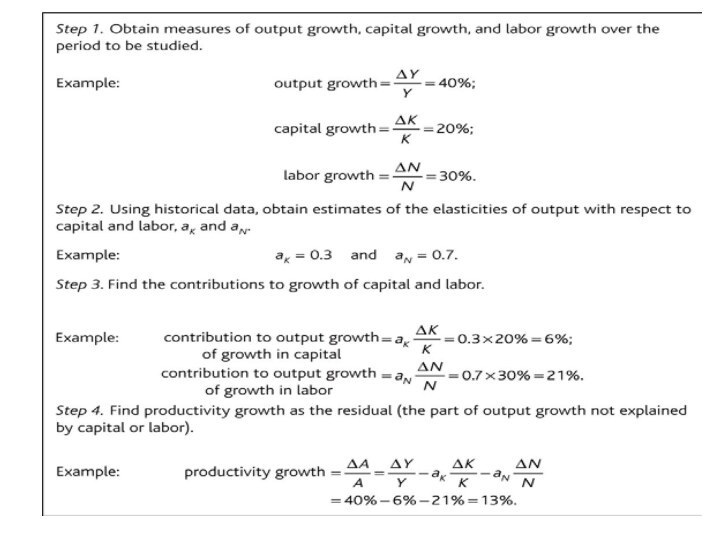

Слайд 13

This can be transformed into a linear model

by taking natural logs of both sides:

ln Y= ln A + α ln K + β ln L (3)

Decompose into growth rate form: the growth accounting equation:

ΔY/Y=ΔA/A + α ΔK/K+ βΔL/L (4)

ΔY/Y= Growth in Output

α (ΔK/K) = Contribution of Capital

(1- α) ΔL/L = Contribution of Labor

ΔA/A = Growth in Total Factor Productivity (TFP)

Growth in TFP represents output growth not accounted for by the growth in inputs.

Слайд 14

The slope coefficients can be interpreted as elasticities.

If

(α + β) = 1, we have constant returns

to scale.

If (α + β) > 1, we have increasing returns to scale.

If (α + β) < 1, we have decreasing returns to scale.

Both α and β are less than 1 due to diminishing marginal productivity

Interpretation

A rise of 10 % in A raises output by 10%.

A rise of 10% in K raises output by α times 10%.

A rise of 10% in L raises output by β times 10%.

For instance; in Unites States, real GDP has grown an average of 3.6 percent per year since 1950.

Of this 3.6 percent, 1.2 percent is attributable to increases in the capital stock, 1.3 percent to increases in the labor input, and 1.1 percent to increases in TFP.

Слайд 16

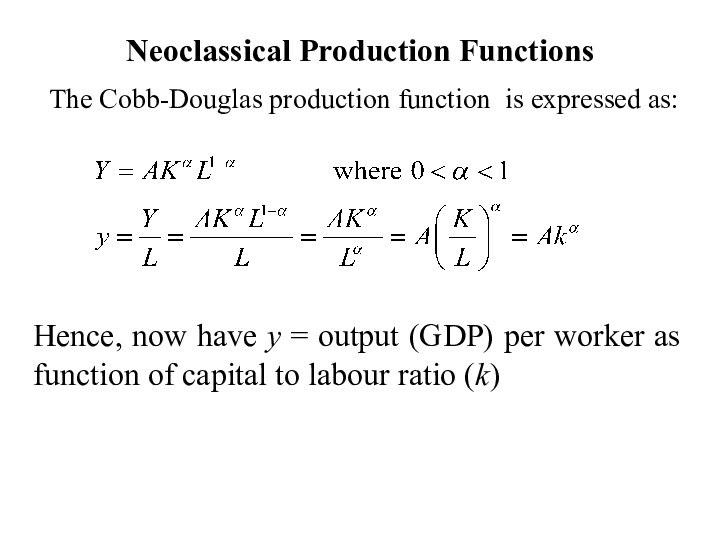

Neoclassical Production Functions

The Cobb-Douglas production function is expressed

as:

Hence, now have y = output (GDP) per worker

as function of capital to labour ratio (k)

Слайд 17

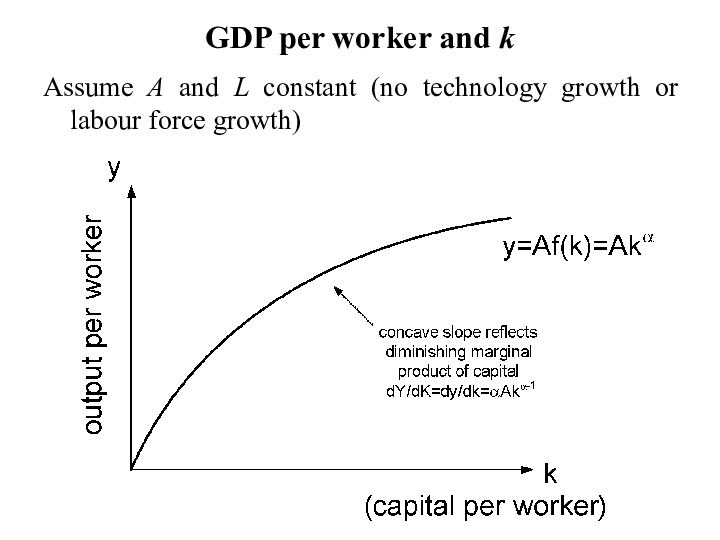

GDP per worker and k

Assume A and L

constant (no technology growth or labour force growth)

Слайд 18

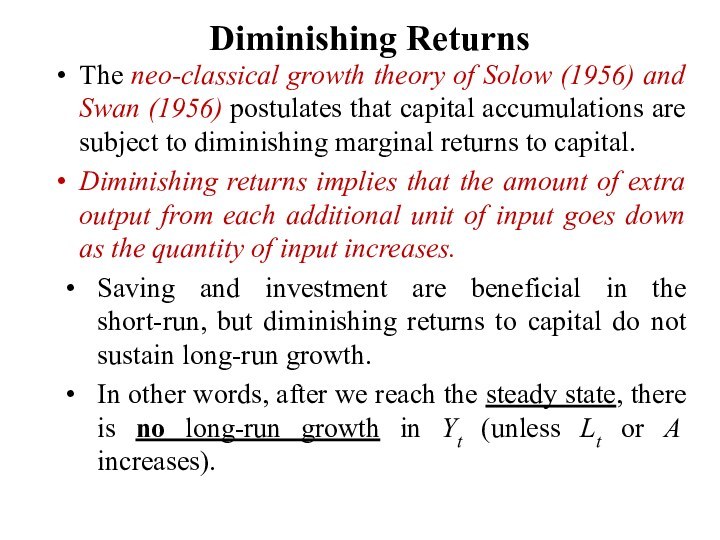

Diminishing Returns

The neo-classical growth theory of Solow (1956)

and Swan (1956) postulates that capital accumulations are subject

to diminishing marginal returns to capital.

Diminishing returns implies that the amount of extra output from each additional unit of input goes down as the quantity of input increases.

Saving and investment are beneficial in the short-run, but diminishing returns to capital do not sustain long-run growth.

In other words, after we reach the steady state, there is no long-run growth in Yt (unless Lt or A increases).

Слайд 19

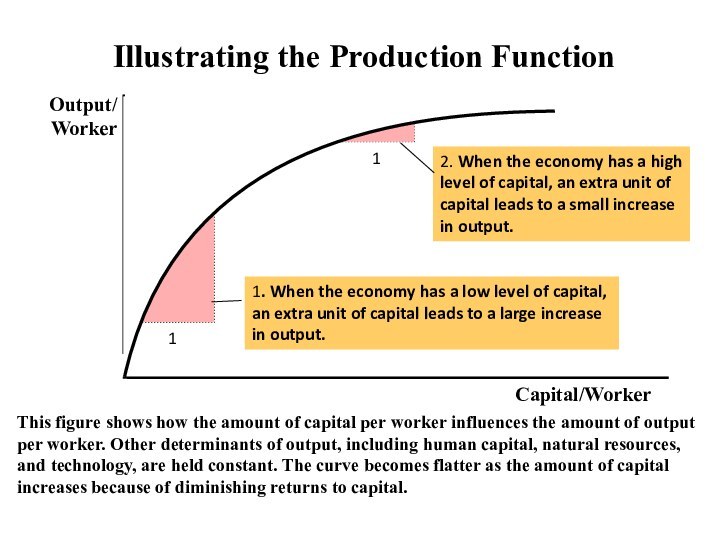

Illustrating the Production Function

This figure shows how

the amount of capital per worker influences the amount

of output per worker. Other determinants of output, including human capital, natural resources, and technology, are held constant. The curve becomes flatter as the amount of capital increases because of diminishing returns to capital.

Слайд 20

Diminishing Returns

If the variable factor of production increases,

the output will increase up to a certain point.

After

a certain point, that factor becomes less productive; therefore, there will eventually be a decreasing marginal return and average product decreases.

Rich countries

High productivity

Additional capital investment leads to a small effect on productivity

Poor countries tend to grow faster than rich countries.

Even small amounts of capital investment may increase workers’ productivity substantially.

Слайд 21

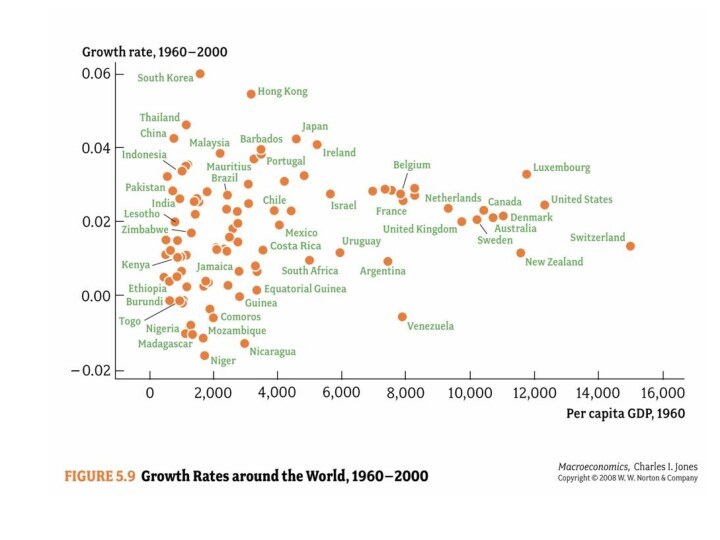

Catch-up effect (Convergence)

Countries that start off poor tend

to grow more rapidly than countries that start off

rich.

Poor countries have the potential to grow at a faster rate than rich countries because diminishing returns are not as strong as in capital-rich countries.

Furthermore, poorer countries can replicate the production methods, technologies, and institutions of developed countries.

The neoclassical approach pioneered by Solow (1956) and subsequently developed by Barrow and Sala-i-Martin (1991, 1995) and Mankiw et al (1992). explains convergence is a result of decreasing returns in physical capital accumulation.

Слайд 22

A second approach explains convergence as resulting primarily

from cross- country knowledge spillovers.

The process of diffusion, or

technology spillover from another country is an important factor behind cross-country convergence.

However, the fact that a country is poor does not guarantee that catch-up growth will be achieved.

The ability of a country to catch-up depends on its ability to absorb new technology, attract capital and participate in global markets, and that is why there is still divergence in the world today.

Слайд 23

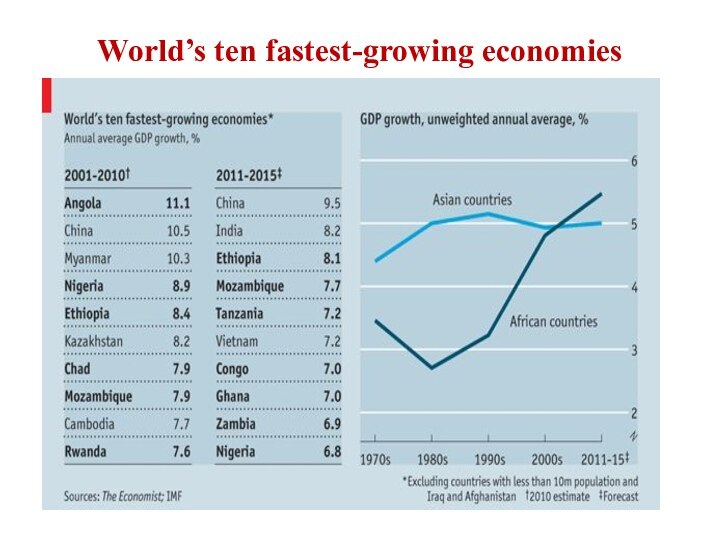

World’s ten fastest-growing economies

Слайд 24

What causes the differences in income over time

and across countries?

The Solow growth model shows how saving,

population growth, and technological progress affect the level of an economy’s output and its growth over time.

Labor grows exogenously through population growth.

Capital is accumulated as a result of savings behavior.

The capital stock is a key determinant of the economy’s output.

But, the capital stock can change over time, and those changes can lead to economic growth.

In particular, two forces influence the capital stock: investment and depreciation.

Слайд 25

Investment refers to the expenditure on new plant

and equipment, and it causes the capital stock to

rise.

Depreciation refers to the wearing out of old capital, and it causes the capital stock to fall.

The saving rate ‘s’ determines the allocation of output between consumption and investment. For any level of k, output is f(k), investment is s f(k), and consumption is

f(k) – sf(k).

On the other hand, investment per worker (i) can be expressed as a function of the capital stock per worker: i= sf(k)

This equation relates the existing stock of capital ‘k’ to the accumulation of new capital ‘i’.

The capital stock next year equals the sum of the capital started with this year plus the amount of investment undertaken this year minus depreciation.

Слайд 26

Depreciation is the amount of capital that wears

out each period ~ 10 percent/year.

kt+1 =kt +It – δ kt

Change in capital stock= investment-Depreciation

Δk = I- δk

Where Δk is the change in the capital stock between one year and the next.

Because investment I equals sf (k), we can write this as:

Δk = sf(k)- δk

The higher the capital stock, the greater the amounts of output and investment.

Yet the higher the capital stock, the greater also the amount of depreciation.

Слайд 27

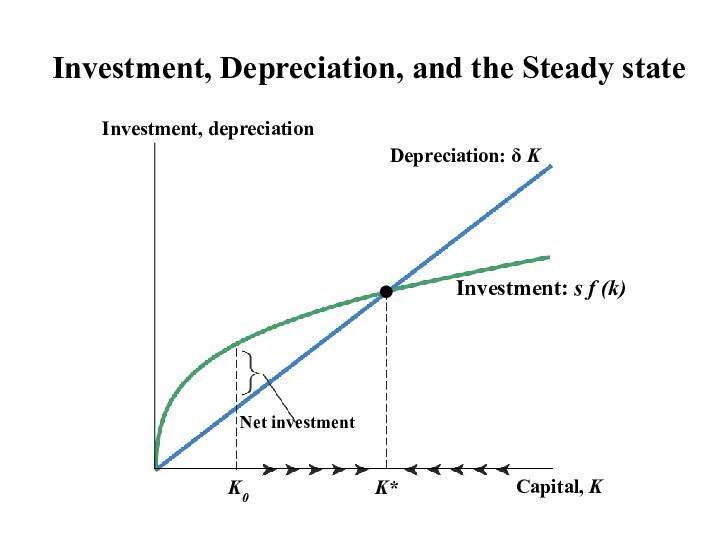

Depreciation: δ K

Investment: s f (k)

Investment, Depreciation, and

the Steady state

Слайд 28

The steady-state level of capital K* is the

level at which investment equals depreciation, indicating that the

amount of capital will not change over time.

Below K* is the level at which investment exceeds depreciation, so the capital stock grows.

Above K*, investment is less than depreciation, so the capital stock shrinks.

In this sense, the steady state represents the long-run equilibrium of the economy.

Слайд 29

The major accomplishment of the Solow model is

the principle of transition dynamics, which states that the

farther below its steady state an economy is, the faster it will grow.

Increases in the investment rate or TFP can increase a country’s steady-state position and therefore increase growth, at least for a number of years.

However, it does not explain why different countries have different investment and productivity rates.

In general, most poor countries have low TFP levels and low investment rates, the two key determinants of steady-state incomes.

Слайд 30

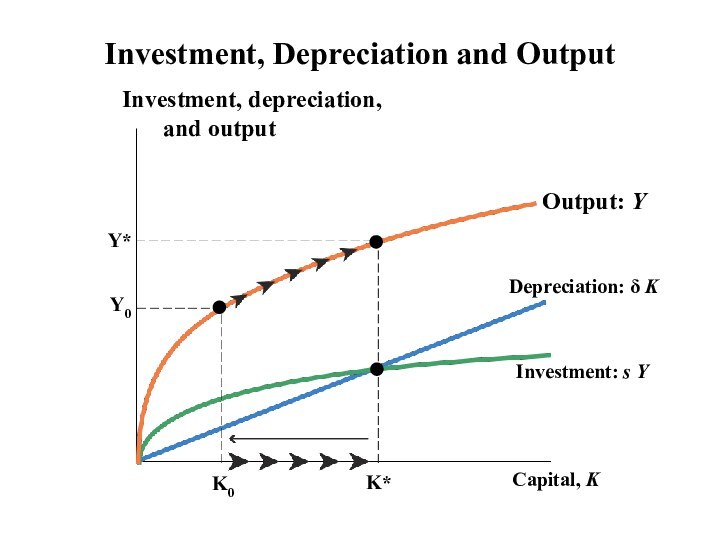

Investment, Depreciation and Output

Output: Y

Depreciation: δ K

Investment: s

Слайд 31

Solving Mathematically for the Steady State

In the steady

state, investment equals depreciation and we can solve mathematically

for it.

In the steady state: Δk = sf(k)- δk=0

= sf(k) = δk

= sAKαL1-α = δk

= sAL1-α = δK/Kα = δ K1-α

= K1-α = (s AL(1- α))/ δ

= K*= L (s A/ δ) (1/1- α)

In the Solow model, diminishing returns to capital eventually force the economy to approach a steady state in which growth depends only on exogenous technological progress.

Слайд 32

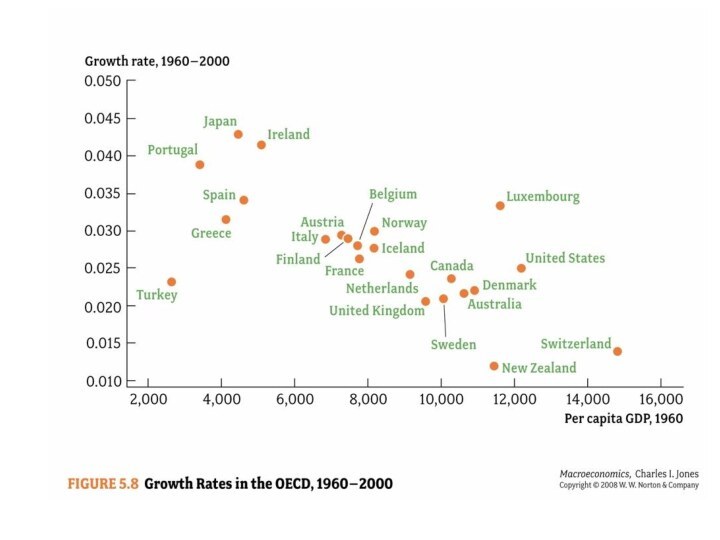

Understanding Differences in Growth Rates

OECD countries that were

relatively poor in 1960 grew quickly while countries that

were relatively rich grew slower.

Solow’s principle of transition dynamics states that the farther below its steady state an economy is, the faster it will grow.

Most poor countries have low TFP levels, low investment rates, and high population growth which are the three key determinants of steady-state incomes.

Countries have more capital because they save a greater part of their income.

Слайд 33

Some Things to Notice

The farther the economy starts

below the steady state level of capital, the faster

the economy initially grows.

Mankiw refers to this as the “catch-up” effect.

This is due to the effect of “diminishing returns”

The amount of extra output from each additional unit of capital goes down as the capital stock gets larger.

If a country is able to increase its productivity, capital will “catch up” quite quickly

Growth slows over time until the capital stock reaches the steady state level.

The Solow model shows that the saving rate is a key determinant of the steady-state capital stock.

However, the rate of saving raises growth only until the economy reaches the new steady state.

Слайд 36

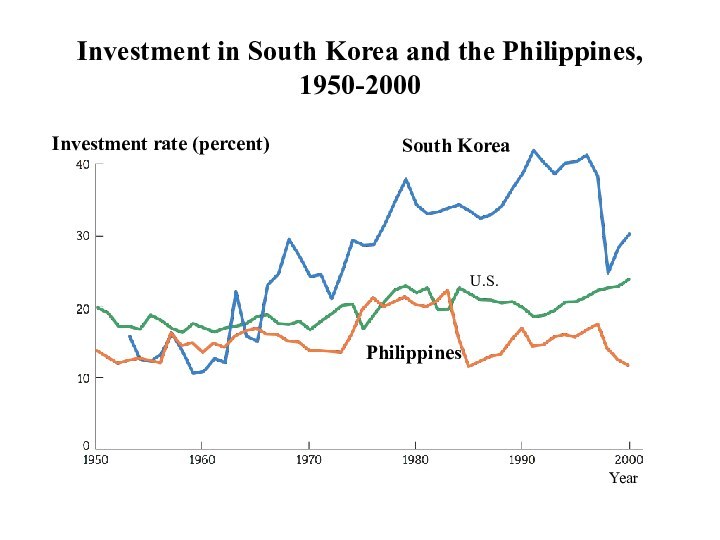

Investment in South Korea and the Philippines,

1950-2000

Слайд 37

Brazil, S. Korea, Philippines

Source: Penn World Table 6.1

(http://pwt.econ.upenn.edu/aboutpwt.html)

Слайд 38

Application: Do Economies Converge?

Unconditional (Absolute) convergence (α-Convergence)

occurs when poor countries will eventually catch up with

the rich countries resulting in similar living standards.

Conditional convergence (β-Convergence):-It will occur, conditional on a number of factors. In other words, it occurs when countries with similar characteristics will converge (savings rate, investment rate, population growth).

No convergence occurs when poor countries do not catch up over time and living standards may diverge.

Слайд 39

Imagine that at the end of their first

year, some students have A averages, whereas others have

C averages. Would you expect the A and C students to converge over the remaining three years of college?

The answer depends on why their first-year grades differed. If the differences arose because some students came from better high schools than others, then you might expect those who were initially disadvantaged to start catching up to their better-prepared peers.

But if the differences arose because some students study more than others, you might expect the differences in grades to persist.

Similarly, if two economies have different steady states, perhaps because the economies have different rates of saving, then we should not expect convergence.

Слайд 40

According to the traditional neoclassical growth theory:

Output

growth results either from increases in labor, increases in

capital, and technological changes.

Closed economies with low savings rates grow slowly in the SR and converge to lower per capita income levels.

Open economies converge at higher levels of per capita income levels.

Traditional neoclassical theory argues that capital flows from rich to poor countries as K-L ratios are lower and investment returns are higher in the latter.

However, in practice, capital flows from rich to rich/poor to rich countries and this is known as the “Lucas paradox.” Why?

Слайд 41

Endogenous Growth Theory

The neo-classical growth theory of Solow

(1956) and Swan (1956) postulates that capital accumulations are

subject to diminishing marginal returns to capital.

Endogenous growth theory (Romer, Lucas) emphasizes different growth opportunities in physical capital and knowledge.

Endogenous growth theory predicts diminishing marginal returns to physical capital, but perhaps not knowledge

The long run growth in GDP per capita in Solow model will depend on TFP growth, which reflects technological progress (which is exogenous in the Solow model).

Technology is exogenous implies that it is not determined within the model (it is exogenous)

Слайд 42

Endogenous growth states that long-run economic growth is

determined by forces that are internal to the economic

system, particularly those forces governing the opportunities and incentives to create technological knowledge.

Endogenous growth theory states technological change arises in large part because of intentional actions taken by people

Endogenous growth theory endogenizes technical change, including human capital, and other forms of knowledge-rich capital in capital stocks.

One drawback of the Solow model is that long-run growth in per capita income is entirely exogenous.

In the absence of exogenous technological growth, income per capita would be static in the long run. This is an implication of diminishing marginal returns to capital.

Слайд 43

To introduce endogenous growth, it is necessary to

have increasing (or at least non-decreasing) returns to capital.

As

in the Solow model, technological change fuels growth.

Technological change arises from research and development (R&D).

Endogenous growth theory rejects the Solow model’s assumption of exogenous technological change.

Advocates of endogenous growth theory argue that the assumption of constant (rather than diminishing) returns to capital is more palatable if ‘K’ is interpreted more broadly; i.e., to view knowledge as a type of capital.

Human capital is the accumulated stock of skills and education

Слайд 44

The largest difference between these two economic growth

models is that the endogenous growth theory argues that

economies do not reach stability, as economies achieve constant returns to capital.

Endogenous growth theory asserts that the rate of economic growth is dependent on whether the country invests in technological or human capital.

In the early 1970s, the rate of growth fell in most industrialized countries. The cause of this slowdown is not well understood.

In the mid-1990s, the rate of growth increased, most likely because of advances in information technology.

A key feature of the endogenous growth model is the absence of diminishing marginal returns to human capital.

This absence of diminishing marginal returns leads to unbounded growth in output per worker.

Endogenous growth theory predicts diminishing marginal returns to physical capital, but perhaps not knowledge.

Слайд 45

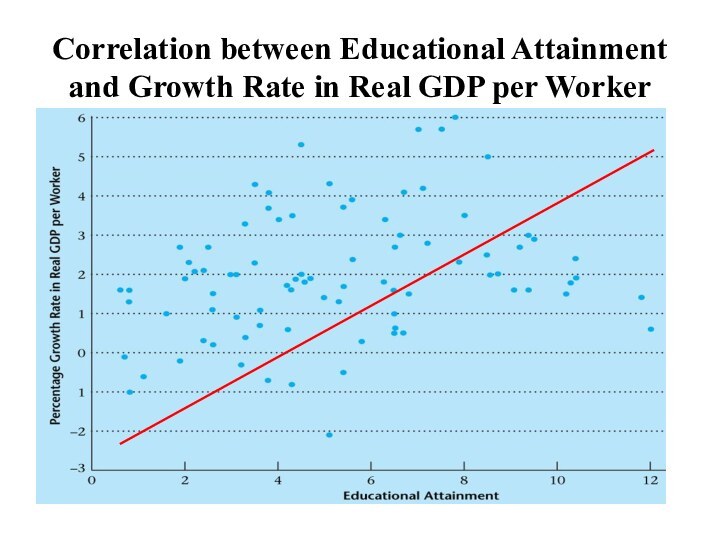

Correlation between Educational Attainment and Growth Rate in

Real GDP per Worker

Слайд 46

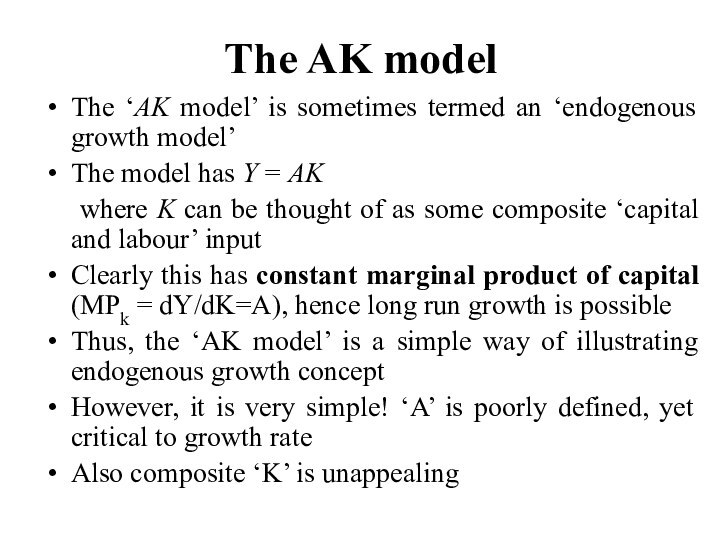

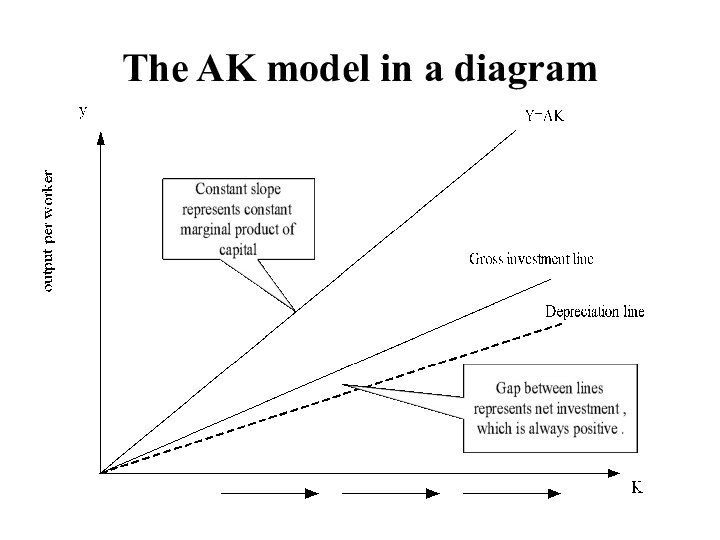

The AK model

The ‘AK model’ is sometimes termed

an ‘endogenous growth model’

The model has Y = AK

where

K can be thought of as some composite ‘capital and labour’ input

Clearly this has constant marginal product of capital (MPk = dY/dK=A), hence long run growth is possible

Thus, the ‘AK model’ is a simple way of illustrating endogenous growth concept

However, it is very simple! ‘A’ is poorly defined, yet critical to growth rate

Also composite ‘K’ is unappealing

Слайд 47

The AK model in a diagram

Where, investment

(i)=s f(k) and depreciation= δ k

Слайд 48

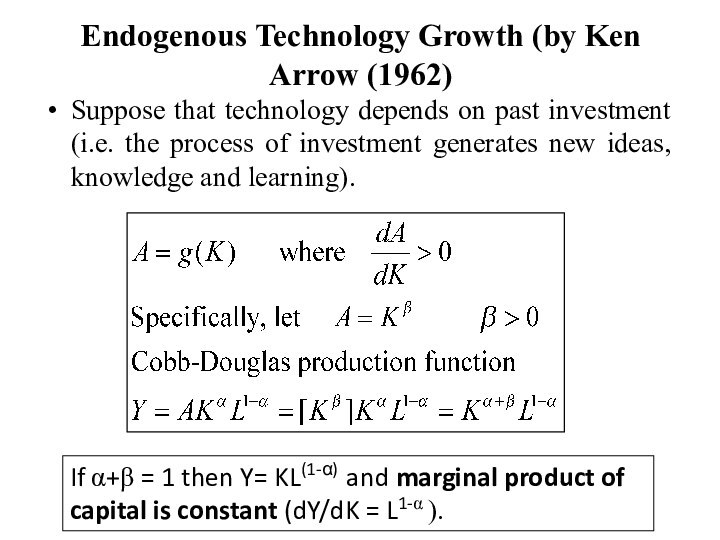

Endogenous Technology Growth (by Ken Arrow (1962)

Suppose

that technology depends on past investment (i.e. the process

of investment generates new ideas, knowledge and learning).

If α+β = 1 then Y= KL(1-α) and marginal product of capital is constant (dY/dK = L1-α ).

Слайд 49

Assuming A=g(K) is Ken Arrow’s (1962) learning-by-doing paper

The

intuition is that learning about technology prevents marginal product

declining.

Слайд 50

No Convergence

Neoclassical growth theory predicts:

Conditional convergence for

economies with equal rates of saving and population growth

and with access to the same technology.

Un-conditional (absolute) convergence for economies with different rates of savings and/or population growth → steady state level of income differ, but growth rates eventually converge

In the endogenous growth model, two identical countries that differ only in their initial incomes will never converge.

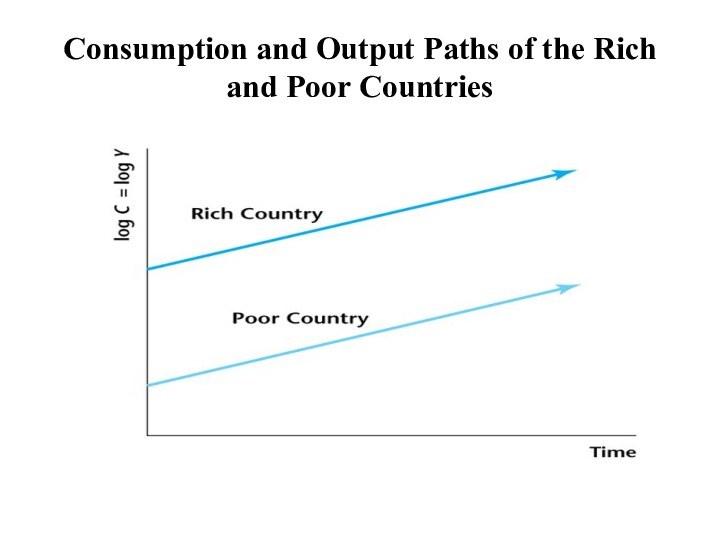

Слайд 51

Consumption and Output Paths of the Rich and

Poor Countries

Слайд 52

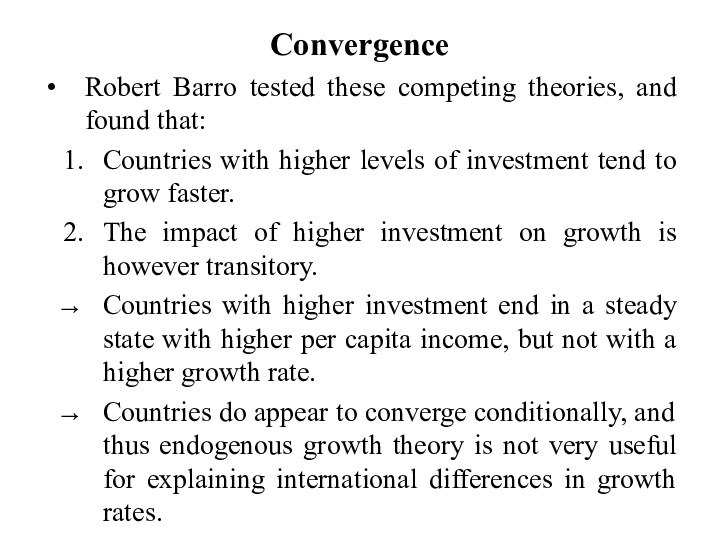

Convergence

Robert Barro tested these competing theories, and found

that:

Countries with higher levels of investment tend to grow

faster.

The impact of higher investment on growth is however transitory.

Countries with higher investment end in a steady state with higher per capita income, but not with a higher growth rate.

Countries do appear to converge conditionally, and thus endogenous growth theory is not very useful for explaining international differences in growth rates.

Слайд 53

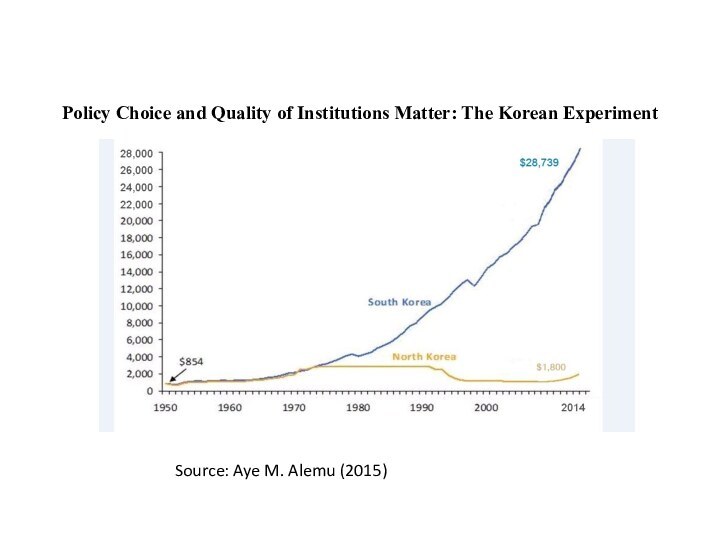

Transformation of the Korean Economy (1945-2005)

Слайд 54

Policy Choice and Quality of Institutions Matter: The

Korean Experiment

Source: Aye M. Alemu (2015)

Слайд 55

Flying geese’ pattern of economic development in East

Asia

The phrase “flying geese pattern of development” was coined

originally by Kaname Akamatsu in the 1930s and it resembles like a wild-geese flying pattern.

The FG pattern of industrial development is transmitted from a lead goose (Japan) to follower geese (NIEs, ASEAN 4, China, etc.).

Wild-geese flying pattern

Слайд 56

Japan succeeded first in modernizing its economy during

the latter half of the 19th century. Despite the

interruption of World War II, it became virtually the sole developed country in Asia in the 1960s.

The second wave of industrialization in East Asia took place in the Asian NIEs known as the four ‘dragons’ or ‘tigers’ (Taiwan, Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore) from the 1950s to the 1970s.

The third wave of industrialization occurred in the leading ASEAN countries (Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia) in the 1980s.

The fourth wave of industrialization in the 1990s was led by China, which had industrialized itself by the 1980s, when its opening up to the world economy by Deng Xiaoping.

Vietnam, one of the newcomer ASEAN countries, followed suit and successfully reformed its economy through ‘Doi Moi’ (renovation)

Currently, the wave of industrialization in East Asia has reached Lao PDR and Cambodia.

Слайд 57

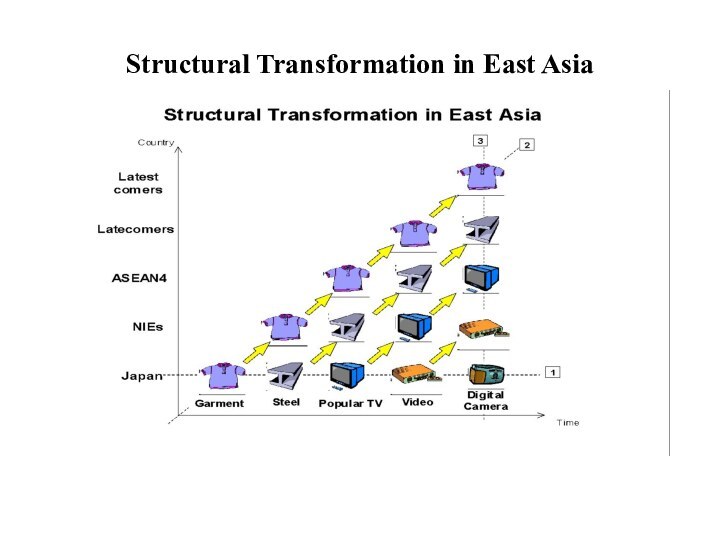

Structural Transformation in East Asia

Слайд 58

Are natural resources a limit to growth?

Argument

Natural resources

- will eventually limit how much the world’s economies

can grow

Fixed supply of nonrenewable natural resources – will run out.

Stop economic growth

Force living standards to fall

Слайд 59

Are natural resources a limit to growth?

Technological progress

Often

yields ways to avoid these limits

Improved use of natural

resources over time

Recycling

New materials

Are these efforts enough to permit continued economic growth?

Слайд 60

Are natural resources a limit to growth?

Prices of

natural resources

Scarcity - reflected in market prices

Natural resource prices

Substantial

short-run fluctuations

Stable or falling - over long spans of time

It depends on our ability to conserve these resources.

Слайд 61

Saving and Investment

Raise future productivity

Invest more current resources

in the production of capital.

Trade-off

Devote fewer resources to produce

goods and services for current consumption.

Слайд 62

Higher savings rate

Fewer resources – used to make

consumption goods

More resources – to make capital goods

Capital stock

increases

Rising productivity

More rapid growth in GDP

Слайд 63

Investment from Abroad

Investment from abroad

Another way for a

country to invest in new capital

Foreign direct investment

Capital investment

that is owned and operated by a foreign entity.

Foreign portfolio investment

Investment financed with foreign money but operated by domestic residents.

Слайд 64

Investment from Abroad

Benefits from investment

Some flow back to

the foreign capital owners.

Increase the economy’s stock of capital

Higher

productivity

Higher wages

State-of-the-art technologies

Слайд 65

Investment from Abroad

World Bank

Encourages flow of capital to

poor countries

Funds from world’s advanced countries

Makes loans to less

developed countries

Roads, sewer systems, schools, other types of capital

Advice about how the funds might best be used

Слайд 66

Investment from Abroad

World Bank and the International Monetary

Fund

Set up after World War II

Economic distress leads to:

Political

turmoil, international tensions, and military conflict

Every country has an interest in promoting economic prosperity around the world.

Слайд 67

Education

Education

Investment in human capital

Gap between wages

of educated and uneducated workers

Opportunity cost: wages forgone

Conveys positive

externalities

Public education - large subsidies to human-capital investment

Problem for poor countries: Brain drain

Слайд 68

Health and Nutrition

Human capital

Education

Expenditures that lead to a

healthier population

Healthier workers

More productive

Wages

Reflect a worker’s productivity

Слайд 69

Health and Nutrition

Right investments in the health of

the population

Increase productivity

Raise living standards

Historical trends: long-run economic growth

Improved

health – from better nutrition

Taller workers – higher wages – better productivity

Слайд 70

Health and Nutrition

Vicious circle in poor countries

Poor countries

are poor

Because their populations are not healthy

Populations are not

healthy

Because they are poor and cannot afford better healthcare and nutrition

Слайд 71

Health and Nutrition

Virtuous circle

Policies that lead to more

rapid economic growth

Would naturally improve health outcomes

Which in

turn would further promote economic growth

Слайд 72

Property Rights & Political Stability

To foster economic growth

Protect

property rights

Ability of people to exercise authority over the

resources they own.

Courts – enforce property rights

Promote political stability

Property rights

Prerequisite for the price system to work

Слайд 73

Property Rights & Political Stability

Lack of property rights

Major

problem

Contracts are hard to enforce

Fraud goes unpunished

Corruption

Impedes the coordinating

power of markets

Discourages domestic saving

Discourages investment from abroad

Слайд 74

Property Rights & Political Stability

Political instability

A threat to

property rights

Revolutions and coups

Revolutionary government might confiscate the capital

of some businesses.

Domestic residents - less incentive to save, invest, and start new businesses.

Foreigners - less incentive to invest

Слайд 75

Free Trade

Inward-oriented policies

Avoid interaction with the rest of

the world

Infant-industry argument

Tariffs

Other trade restrictions

Adverse effect on economic growth

Слайд 76

Free Trade

Outward-oriented policies

Integrate into the world economy

International trade

in goods and services

Economic growth

Amount of trade – determined

by

Government policy

Geography

Easier to trade for countries with natural seaports

Слайд 77

Research and Development

Knowledge – public good

Government–encourages research and

development

Farming methods

Aerospace research (Air Force; NASA)

Research grants

National Science

Foundation

National Institutes of Health

Tax breaks

Patent system

Слайд 78

Population Growth

Large population

More workers to produce goods and

services

Larger total output of goods and services

More consumers

Stretching natural

resources

Malthus: an ever-increasing population

Strain society’s ability to provide for itself

Mankind - doomed to forever live in poverty

Слайд 79

Population Growth

Diluting the capital stock

High population growth

Spread the

capital stock more thinly

Lower productivity per worker

Lower GDP

per worker

Reducing the rate of population growth

Government regulation

Increased awareness of birth control

Equal opportunities for women

Слайд 80

Population Growth

Promoting technological progress

World population growth

Engine for technological

progress and economic prosperity

More people = More scientists, more

inventors, more engineers

Слайд 81

Summary

International differences in income per person can be

attributed to either:

differences in the factors of production,

such as the quantities of physical and human capital, or

Differences in the efficiency with which economies use their factors of production.

A final hypothesis is that both factor accumulation and production efficiency are driven by a common third variable: quality of the nation’s institutions , including the government’s policymaking process.

Bad policies such as high inflation, excessive budget deficits, widespread market interference, and rampant corruption, often go hand in hand.

Слайд 82

Summary

The Solow growth model has emphasized the importance

of savings or investment ratio as the main determinant

of short-run economic growth.

The neo-classical growth theory of Solow (1956) and Swann (1956) postulates that capital accumulations are subject to diminishing returns.

The long run growth in GDP per capita, will depend on TFP growth, which reflects technological progress.

In the absence of exogenous technological growth, income per capita would be static in the long run.

Слайд 83

Technological progress, though important in the long-run, is

regarded as exogenous to the economic system.

The Solow Model

predicts catch-up growth (convergence in growth rate) on the basis that poor economies will grow faster compared to rich ones.

One drawback of the Solow model is that long-run growth in per capita income is entirely exogenous.

Слайд 84

Investment, Depreciation and Output

Output: Y

Depreciation: δ K

Investment: s

Слайд 85

The Endogenous growth theory believe that human capital

and innovation capacity are the main sources of long-term

economic growth.

Human capital is the accumulated stock of skills and education

Unlike Solow model, Endogenous growth theory endogenizes technical change.

Technological change arises from research and development (R&D).

A key feature of the endogenous growth model is the absence of diminishing marginal returns to human capital.

The endogenous growth models suggest that convergence would not occur at all (mainly due to the fact that there are increasing returns to scale).

Слайд 87

Generally, the following are growth drivers:

Growth in physical

capital stock (capital deepening)

Growth in the size of active

labor force available for production

Growth in the quality of labor (human capital)

Technological progress and innovation

Institutions-including maintaining the rule of law, stable macroeconomic and political stability

Rising demand for goods and services-either led by domestic demand or from external trade.