- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Culture of great Вritain

Содержание

- 2. GENERAL FACTS English culture tends to

- 3. Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland share

- 4. British art has had a

- 5. British studios, playwrights, directors, and

- 6. British composers have found devoted listeners

- 7. From medieval time to the

- 8. The independent Arts Council, formed in

- 9. The British Museum in London houses

- 10. Among the many libraries and

- 11. Theatres of Great Britain

- 12. THE ENGLISH DRAMA Drama of the Middle Ages

- 13. Through practically a thousand years

- 14. It is probable, had not

- 15. At first only the priests took

- 16. Both the Mystery and the

- 17. Most of these farces came

- 18. From these “interludes”(literally “between the

- 19. 16th Century English Theatre

- 20. ELIZABETHAN THEATRES The theatre as a

- 21. The great popularity of plays

- 22. Companies of actors were kept

- 23. Regulation and Licensing of Plays The

- 24. The sovereign attempted to regulate

- 25. During the reign of Mary,

- 26. Objections to Playhouses Respectable people and

- 27. that taverns and disreputable houses

- 28. Elizabeth’s comedy was to compromise.

- 29. Players were forbidden to establish

- 30. Companies of Actors In 1578 six

- 31. Soon the professional actor gained

- 32. Playhouses The number of playhouses steadily

- 33. At the end of the

- 34. England was the last of

- 35. Composition and Ownership of Plays The

- 36. If the piece became popular,

- 37. Performances Public performances generally took place

- 38. The house itself was not

- 39. Court Comedies There were two groups

- 40. One of this was the

- 41. Court Masques The success of the masque

- 42. The king and queen, each, provided

- 43. The Old English Pantomime The old English

- 44. The story was usually founded

- 45. Early in 1723 the managers

- 46. Chamberlain’s Men Chamberlain’s Men, a theatrical

- 47. In 1594 their London home

- 48. Later, they presumably used the

- 49. Shakespeare was the company’s principal

- 50. FAMOUS ENGLISH PLAYWRIGHTS AND ACTORS OF THE 16TH CENTURY

- 51. Francis Beaumont (1584 – 1616)John Fletcher (1579-1625)Robert

- 52. 17th CENTURY ENGLISH THEATRE

- 53. The Restoration Charles II (1660

- 54. The managers deserted the repertory

- 55. When the producers turned away

- 56. Famous English Actors and Playwrights of the 17th Century

- 57. Thomas Betterton (1635? – 1710)John Dryden (1631 -1700)Nathaniel Lee (1653-1692)William Congreve (1670-1729)

- 58. Famous English Actors and Playwrights of the 18th Century

- 59. David Garrick (1717-1779)Oliver Goldsmith (1730? -1774)Edmund Kean

- 60. Famous English Actors and Playwrights of the 19th Century

- 61. Lewis Casson (1875 – 1969)Henry Irving (1838-1905)Tom Taylor (1817-1880)Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

- 62. 20th CENTURY ENGLISH THEATRE The English stage

- 63. His plays are conspicuous for

- 64. The 1930-s saw a new

- 65. Center 42 is the most

- 66. Famous English Actors, Playwrights, and Directors of the 20th Century

- 67. Peter Brook (1925- )Vivien Leigh (1918 –

- 68. Скачать презентацию

- 69. Похожие презентации

GENERAL FACTS English culture tends to dominate the formal cultural life of the United Kingdom, but Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have also made important contributions, as have the cultures that British colonialism brought into

Слайд 3 Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland share fully

in the common culture but also preserve lively traditions

that predate political union with England.Слайд 4 British art has had a tremendous

impact on world culture. Writers from every part of

the United Kingdom, joined by immigrants from parts of the former British Empire and the Commonwealth, have enriched the English language and world literature alike with their work.Слайд 5 British studios, playwrights, directors, and actors

have been remarkable pioneers of stage and screen. British

comedians have brought laughter to diverse audiences and been widely imitated.Слайд 6 British composers have found devoted listeners around

the world, as have various contemporary pop groups and

singer-songwriters. British philosophers have had a tremendous influence in shaping the course of scientific and moral inquiry.Слайд 7 From medieval time to the present,

this extraordinary flowering of the arts has been encouraged

at every level of society. Early royal patronage played an important role in the development of the arts in Britain, and since the mid 20th century the British government has done much to foster their growth.Слайд 8 The independent Arts Council, formed in 1946,

supports many kinds of contemporary creative and performing arts.

The United Kingdom contains many cultural treasures. It is home to a wide range of learned societies, including the British Academy, the Royal Geographical Society, and the Royal Society of Edinburgh.Слайд 9 The British Museum in London houses historical

artifacts from all parts of the globe. London is

also home to many museums and theatres. Cultural institutions also abound throughout the country.Слайд 10 Among the many libraries and museums

of interest in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland are

the Royal Museum, the Museum of Scotland, and the Writers’ Museum in Edinburgh, the Museum of Scottish Country Life in Glasgow, the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, and the Ulster Museum in Belfast.Слайд 13 Through practically a thousand years while

the European theatre was “dark” the Christian Church was

unable to stamp out completely the festive element among the common people that manifested itself particularly at the spring planting time and the harvest season.Слайд 14 It is probable, had not the

church itself responded to the primitive desire of people

to “act out” the stories of their lives that secular drama would have sprung up in the place of the Mystery (Miracle) and Morality plays of the Middle Ages.Слайд 15 At first only the priests took part

acting out the events from the lives of Christ

and the saints and the portrayal took place in the Church proper. Later as the performances grew more elaborate and space became an important item the Mysteries and Miracles were pushed out into the courtyards of the churches and laymen began to take part in the acting.Слайд 16 Both the Mystery and the Morality

plays were often long winded and frequently dull. To

relieve the tedium “interludes” were presented which were nothing more nor less than slapstick farces as a rule more distinguished for their vulgarity than their humour.Слайд 17 Most of these farces came originally

from France or Italy and dealt either with the

subject of sex or digestion. At their best, however, they carry on the true tradition of the Greek comedy writers and the Roman Plautus and Terence.Слайд 18 From these “interludes”(literally “between the games”,

which was their actual use in Italy) developed a

swift moving farce that was acted independently of any other performance. The best and most famous of these farces of the Middle Ages is the French Farce of Pierre Pathelin.

Слайд 20

ELIZABETHAN THEATRES

The theatre as a public

amusement was an innovation in the social life of

the Elizabethans, and it immediately took the general fancy. London’s first theatre was built when Shakespeare (1564-1616) was about twelve years old; and the whole system of the Elizabethan theatrical world came into being during his lifetime.Слайд 21 The great popularity of plays of

all sorts led to the building of playhouses both

public and private, to the organization of innumerable companies of players both amateur and professional, and to countless difficulties connected with the authorship and licensing of plays.Слайд 22 Companies of actors were kept at

the big baronial estates of Lord Oxford, Lord Buckingham

and others. Many strolling troupes went about the country playing wherever they could find welcome. They commonly consisted of three, or at most four men and a boy, the latter to take the women’s parts. They gave their plays in pageants, in the open squares of the town, in the halls of noblemen and other gentry, or in the courtyards of inns.

Слайд 23

Regulation and Licensing of Plays

The control

of these various companies soon became a problem to

the community. Some of the troupes, which had the impudence to call themselves “Servants” of this or that lord, were composed of low characters, little better than vagabonds, causing much trouble to worthy citizens.Слайд 24 The sovereign attempted to regulate matters

by granting licenses to the aristocracy for the maintenance

of troupes of players, who might at any time be required to show their credentials. For a time it was also a rule that these performers should appear only in the halls of their patrons; but this requirement, together with many other regulations, was constantly ignored.Слайд 25 During the reign of Mary, the

rules were strict. Elizabeth granted the first royal patent

to the Servants of the Earl of Leicester in 1574. These “Servants” were James Burbage and four partners. Under Elizabeth political and religious subjects were forbidden on the stage.

Слайд 26

Objections to Playhouses

Respectable people and officers

of the Church frequently made complaint of the growing

number of play-actors and shows at the Elizabethan epoch. They said that the plays were often lewd and profane, that play-actors were mostly vagrant, irresponsible, and immoral people;Слайд 27 that taverns and disreputable houses were

always found in the neighborhoods of the theatres, and

that the theatre itself was a public danger in the way of spreading disease. The streets were overcrowded after performances; beggars and loafers infested the theatre section, crimes occurred in the crowd, and prentices played truant in order to go to the play.Слайд 28 Elizabeth’s comedy was to compromise. She

regulated the abuses, but allowed the players to thrive.

One order for the year 1576 prohibited all theatrical performances within the city boundaries; but it was not strictly enforced.Слайд 29 Players were forbidden to establish themselves

in the city, but could not be prevented from

building their playhouses just across the river, outside the jurisdiction of the Corporation and yet within easy reach of the play-going public.

Слайд 30

Companies of Actors

In 1578 six companies

were granted permission by special order of the queen

to perform plays. They were the Children of the Chapel Royal, Children of Saint Paul’s, the Servants of the Lord Chamberlain, Servants of Lords Warwick, Leicester and Essex.Слайд 31 Soon the professional actor gained something

in the public esteem, and occasionally became a recognized

and solid member of society. Theatrical companies were gradually transformed from irregular associations of men dependent on a favor of a lord, to stable business organizations; and in time the professional actor and the organized company triumphed completely over the stroller and the amateur.

Слайд 32

Playhouses

The number of playhouses steadily increased.

Besides the three already mentioned, there were in Southwark

the Hope, The Rose, the Swan, and the Newington Butts. Most famous of all were the Globe, built in 1598 by Richard Burbage (1567-1619), and the Fortune, built in 1599.Слайд 33 At the end of the rein

of Elizabeth there were eleven theatres in London, including

public and private houses. Various members of the royal family were the ostensible patrons of the new companies. The boys of the choirs and Church schools were trained in acting.Слайд 34 England was the last of European

countries to accept women on the stage. In the

year 1629 a visiting company of French players gave performances at Blackfriars, with actresses.

Слайд 35

Composition and Ownership of Plays

The plays

were the property, not of the author, but of

the acting companies. Aside from the costly costumes, they formed the most valuable part of the company’s capital. The parts were learned by the actors, and the manuscript locked up.Слайд 36 If the piece became popular, rival

managers often stole it by sending to the performance

a clerk who took down the lines in shorthand. Neither authors nor managers had any protection from pirate publishers, who frequently issued copies of successful plays without the consent of either.

Слайд 37

Performances

Public performances generally took place in

the afternoon, beginning about 3 o’clock and lasting perhaps

two hours. Candles were used when daylight began to fade. The beginning of the play was announced by the hoisting of a flag and the blowing of a trumpet. There were playbills, those for tragedy being printed in red.Слайд 38 The house itself was not unlike

a circus, with a good deal of noise and

dirt. Servants, grooms, prentices and mechanics jostled each other in the pit, while more or less gay companies filled the boxes. Women of respectability were few, yet sometimes they did attend; and if they were very careful of their reputations they wore masks.

Слайд 39

Court Comedies

There were two groups of

plays in the 16th century, which belonged neither to

the democratic, popular class, nor to the Pseudo-classical species fostered by the academic circles.Слайд 40 One of this was the court

comedy, designed especially as a compliment to the queen;

the other was the masque, in which the aristocracy and royalty itself took part as actors. The court comedy was in a sense, a variation, or the specialization of the pastoral, brought into England from Italy chiefly by John Lyly (1553-1606).

Слайд 41

Court Masques

The success of the masque depended

upon the architect, the scene painter, decorator and ballet

master. In the course of time considerable importance was given also to singing and instrumental music. Among the poets engaged to write masque librettos were Jonson, Beaumont, Fletcher, and most of the other talented writers of the day.Слайд 42 The king and queen, each, provided the

masque at Christmas. There remain more than thirty examples

of this sort of play written during the reign of Charles I and James I.

Слайд 43

The Old English Pantomime

The old English pantomime

was modeled with certain modifications upon the masque of

the Elizabethan and the Stuart days.Слайд 44 The story was usually founded upon

a classical subject, was illustrated with music and grand

scenic effects, and to this was later added a comic transformation after the Italian style. Harlequin was turned into a magician, who, by a touch of his bat, could transform a palace into a hut, men and women into wheelbarrows and chairs.Слайд 45 Early in 1723 the managers of

Drury Lane, in rivalry with Rich, produced a pantomime

which may be considered as the first English pantomime. Not to be outdone, in December of the same year, Rich brought out his famous Necromancer or Harlequin Executed, which far surpassed in splendor all that had yet been seen.

Слайд 46

Chamberlain’s Men

Chamberlain’s Men, a theatrical company

with which Shakespeare (1564-1616) was intimately connected for most

of his professional career as a dramatist and the most important company of players in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.Слайд 47 In 1594 their London home was

for a time a theatre in Newington Butts (a

village not far south of London Bridge) and after that most probably at the Cross Keys Inn in the city itself.Слайд 48 Later, they presumably used the theatre,

situated in Shoreditch, since this was owned by the

father of Richard Burbage, their leading actor. In the autumn of 1599, the company was rehoused in the Globe Theatre; this was their most famous home.Слайд 49 Shakespeare was the company’s principal dramatist

(he also acted with them), but in addition to

his plays, works by Ben Jonson, Thomas Dekker, and the partnership of Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher were also presented. The company ceased to exist when, at the outbreak of Civil War in 1642, the theatres were closed and remained so until the Restoration 18 years later.

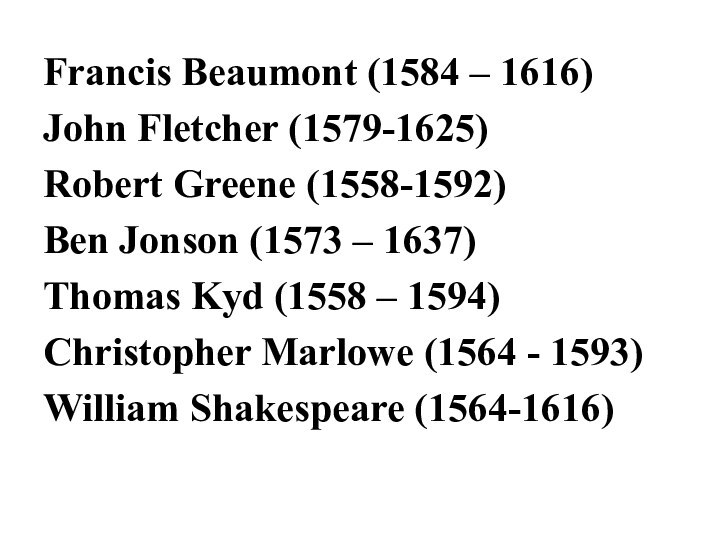

Слайд 51

Francis Beaumont (1584 – 1616)

John Fletcher (1579-1625)

Robert Greene

(1558-1592)

Ben Jonson (1573 – 1637)

Thomas Kyd (1558 – 1594)

Christopher

Marlowe (1564 - 1593)William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

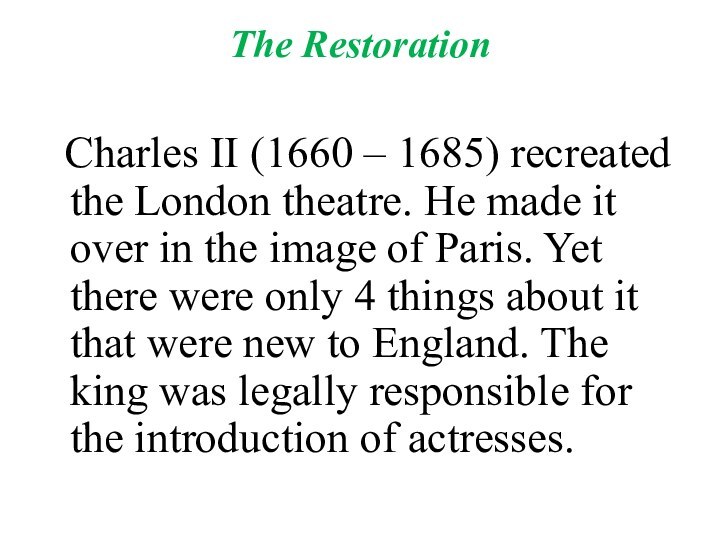

Слайд 53

The Restoration

Charles II (1660 – 1685)

recreated the London theatre. He made it over in

the image of Paris. Yet there were only 4 things about it that were new to England. The king was legally responsible for the introduction of actresses.Слайд 54 The managers deserted the repertory system

that had given the English such a variety of

drama, and they put on plays for long runs. Their playwrights gave the audience “classic” tragedies after the pattern of the French.Слайд 55 When the producers turned away from

the Elizabethan type of public playhouse and installed proscenium

arches and scenic devices in roofed-over theatres, they were following the pattern of the English court masque, whose technique was Italian.

Слайд 57

Thomas Betterton (1635? – 1710)

John Dryden (1631 -1700)

Nathaniel

Lee (1653-1692)

William Congreve (1670-1729)

Слайд 59

David Garrick (1717-1779)

Oliver Goldsmith (1730? -1774)

Edmund Kean (1787-1833)

William

Macready (1793-1873)

Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816)

Sarah Kemble Siddons (1765 –

1831)

Слайд 61

Lewis Casson (1875 – 1969)

Henry Irving (1838-1905)

Tom Taylor

(1817-1880)

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

Слайд 62

20th CENTURY ENGLISH THEATRE

The English stage of

the 20th century has produced on the whole theatrical

rather than literary drama. It was Bernard Shaw who lifted the realistic drama to its highest potentiality by making it primarily intellectual drama, the intellectual brilliancy of which is ultimately enjoyable.Слайд 63 His plays are conspicuous for abundantly

witty dialogue. John Galsworthy, who enjoyed the widest vogue

at the time, was another flare-up. His utterly serious and emotional plays, such as The Silver Box, Strife, Justice, Loyalties and Escape, were the best of their kind and gave the most complete picture of English bourgeois society in the 20th century.Слайд 64 The 1930-s saw a new upheaval

of democratic culture in Great Britain, its main feature

being the mass character and vigorous protest against war, fascism and reaction in ideology. The working class theatre was at its height. They had their own theatre and drama groups, the Unity Theatre in London and Theatre Workshop in the East End being the most famous.Слайд 65 Center 42 is the most recent

development in the working class theatre. It was founded

by Arnold Wesker, a well-known dramatist, and was supported by the trade unions. It awakened the interest of the audiences in genuine culture.

Слайд 67

Peter Brook (1925- )

Vivien Leigh (1918 – 1967)

Laurence Kerr Olivier (1907 – 1989)

John Osborne (1929-1994)

Harold Pinter (1930-2008)

John Boynton Priestley (1894-1984)

Tom Stoppard (1937- )

Arnold Wesker (1932- )