Слайд 2

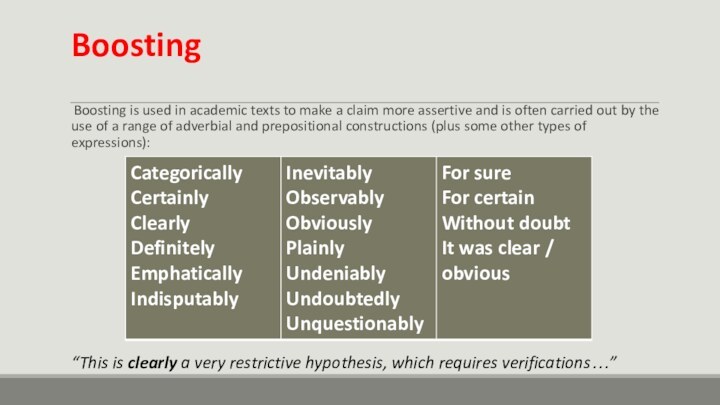

Boosting

Boosting is used in academic texts to make

a claim more assertive and is often carried out

by the use of a range of adverbial and prepositional constructions (plus some other types of expressions):

“This is clearly a very restrictive hypothesis, which requires verifications…”

Слайд 3

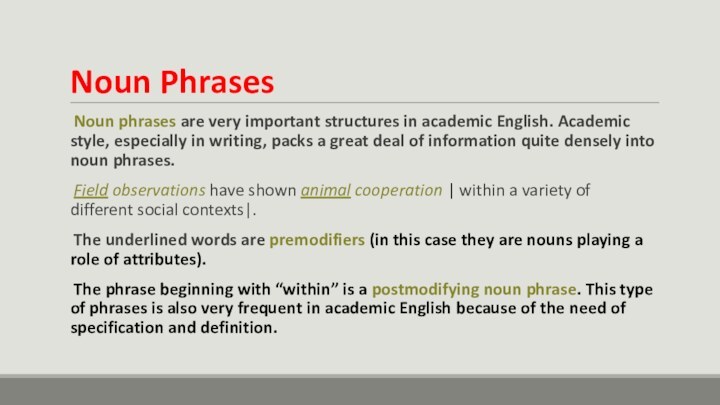

Noun Phrases

Noun phrases are very important structures in

academic English. Academic style, especially in writing, packs a

great deal of information quite densely into noun phrases.

Field observations have shown animal cooperation | within a variety of different social contexts|.

The underlined words are premodifiers (in this case they are nouns playing a role of attributes).

The phrase beginning with “within” is a postmodifying noun phrase. This type of phrases is also very frequent in academic English because of the need of specification and definition.

Слайд 4

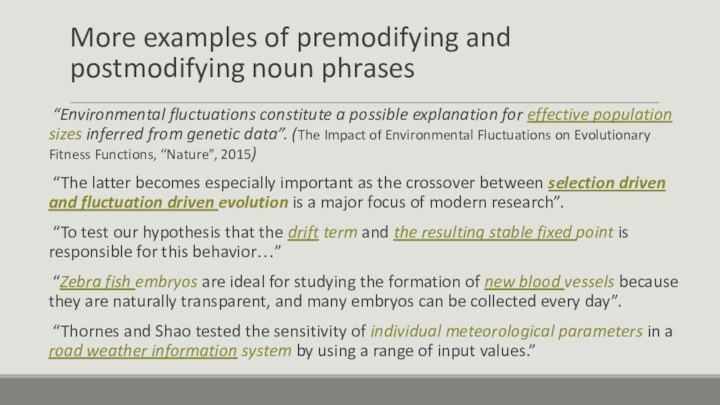

More examples of premodifying and postmodifying noun phrases

“Environmental

fluctuations constitute a possible explanation for effective population sizes

inferred from genetic data”. (The Impact of Environmental Fluctuations on Evolutionary Fitness Functions, “Nature”, 2015)

“The latter becomes especially important as the crossover between selection driven and fluctuation driven evolution is a major focus of modern research”.

“To test our hypothesis that the drift term and the resulting stable fixed point is responsible for this behavior…”

“Zebra fish embryos are ideal for studying the formation of new blood vessels because they are naturally transparent, and many embryos can be collected every day”.

“Thornes and Shao tested the sensitivity of individual meteorological parameters in a road weather information system by using a range of input values.”

Слайд 5

Nominalisation

Nominalizations include nouns which express verb-type and adjective-type

meanings. They are more frequent in written academic style.

“All individuals (n = 7) had simultaneous access to the apparatus”. (Normal style would be: “All individuals accessed the apparatus simultaneously”)

“The time lag between marking and first recapture was higher than the lag between second and third recapture” (NOT “The time lag between when we marked the animals and when we first recaptured them…”)

Compare everyday style: “I decided to start a new experiment” and academic style: “The decision was (taken) to start a new experiment”.

Слайд 6

Using it, this and that

Reference to textual segments

is an important aspect of academic style. The impersonal

pronoun it and the demonstrative pronouns this and that are used in different ways to organize references to text segments and are frequently not interchangeable.

“They differentiated between a cooperative and solitary setting depending on the availability of a partner, and waited for the partner to come if it was delayed.”

“Low-luminance flickering patterns are perceived to modulate at relatively high rates. This occurs even though peak sensitivity is shifted…”

Слайд 7

Impersonal constructions

It-constructions:

It is possible that the apparent lack

of understanding in the current study is specific for

the paradigm used. It seems that the ravens had problems with inhibiting to pull when the partner was absent…

Existential there

“However, there is mixed evidence for social anointing in Sapajus.”

Third person self-reference

Academic writers often refer to themselves as “the author”, “the researcher”, and often refer to their work impersonally, especially in abstracts and summaries:

“The author focuses on the conflicts, stresses, and transformations…”

Слайд 8

Sentence patterns

Composite (both complex and compound) sentences are

very common in academic writing. In complex sentences different

types of subordinate clauses are used: subjects, object, predicate, attributive.

“Nevertheless, all these animals did spontaneously and successfully cooperate in the experimental task, suggesting that they can achieve cooperation through acting apart together [object subordinate clause], most probably motivated by a mutual attraction to the apparatus and the food.”

“Moreover, the distinction between species that do or do not understand the need and role of a partner [attributive subordinate clause] is not that clear-cut, because…”

Слайд 9

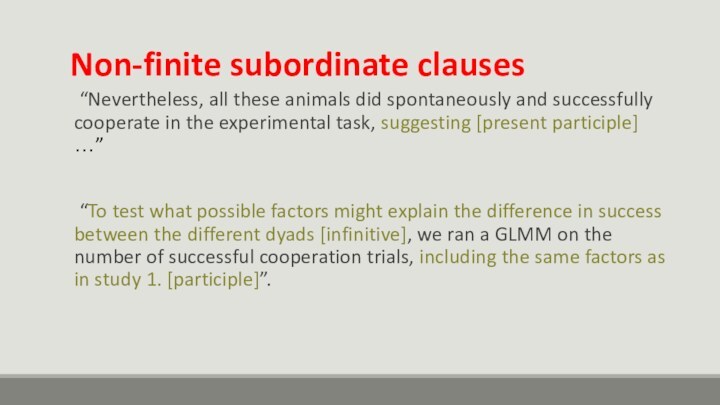

Non-finite subordinate clauses

“Nevertheless, all these animals did spontaneously

and successfully cooperate in the experimental task, suggesting [present

participle] …”

“To test what possible factors might explain the difference in success between the different dyads [infinitive], we ran a GLMM on the number of successful cooperation trials, including the same factors as in study 1. [participle]”.

Слайд 10

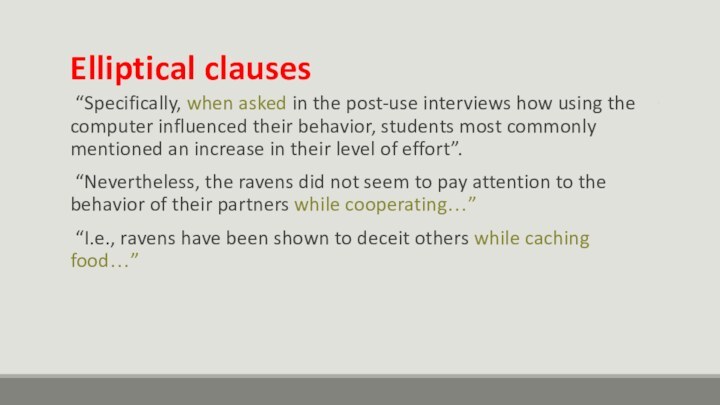

Elliptical clauses

“Specifically, when asked in the post-use interviews

how using the computer influenced their behavior, students most

commonly mentioned an increase in their level of effort”.

“Nevertheless, the ravens did not seem to pay attention to the behavior of their partners while cooperating…”

“I.e., ravens have been shown to deceit others while caching food…”

Слайд 11

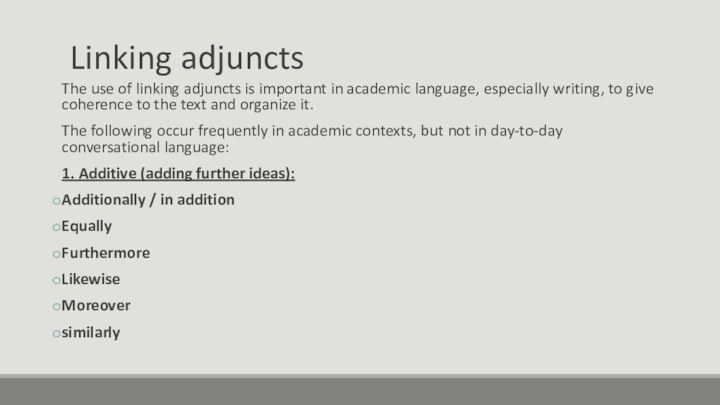

Linking adjuncts

The use of linking adjuncts is important

in academic language, especially writing, to give coherence to

the text and organize it.

The following occur frequently in academic contexts, but not in day-to-day conversational language:

1. Additive (adding further ideas):

Additionally / in addition

Equally

Furthermore

Likewise

Moreover

similarly

Слайд 12

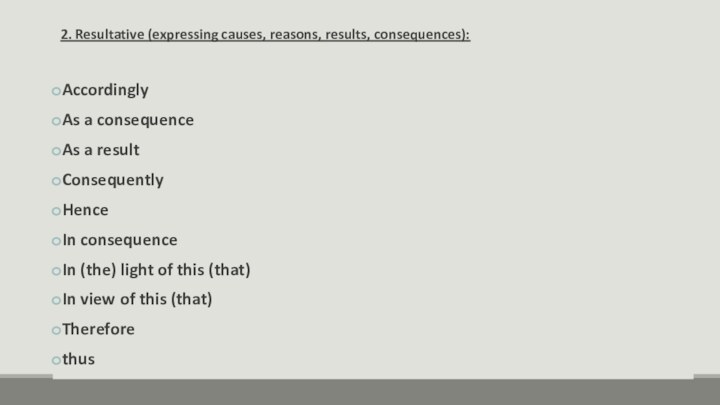

2. Resultative (expressing causes, reasons, results, consequences):

Accordingly

As a

consequence

As a result

Consequently

Hence

In consequence

In (the) light of this (that)

In

view of this (that)

Therefore

thus

Слайд 13

3. contrastive: (contrasting, opposing)

by/in contrast

Conversely

However

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

On the contrary

On the

one hand …. On the other hand

Слайд 14

4. organizational (organizing and structuring the text, listing):

Firstly,

secondly, thirdly

Finally

In brief

In conclusion (to conclude)

In its (their) turn

In short

In sum (to sum up, summing up, to summarize)

In summary

Lastly

Respectively

subsequently

Слайд 15

Linking adjuncts. Examples

However, the ravens did seem to

pay attention to and act upon the outcome of

a cooperative interaction

In particular, we think that the larger the difference in dominance rank, the fewer direct competition is at play

Although the experimenter in our study placed the two rewards within the dyadic setting with ‘the intention’ of an equal reward division, sometimes one of the two birds got two rewards, whereas the other got none.

Alternatively, this pattern may be obtained by associative learning, where a negative experience leads animals not to act anymore.

In contrast, ‘cheaters’ remained motivated to pull (Fig. 3b).

Therefore, more controlled experiments in which defection rates can be manipulated are needed to precisely study the proximate mechanisms

Finally, the results of this study suggest that ravens do not understand the need of a partner while cooperating