- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

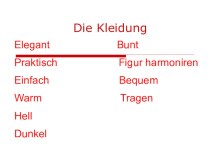

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4)

Содержание

- 2. I. Historical background to the New StandardII.

- 3. III. NE Consonant System:Vocalisation of ‘r’;IV. NE Morphology and Syntax.

- 4. 1476 Caxton introduced the printing press to

- 5. The late Middle Ages (14th c.) had

- 6. Nonetheless Latin still had great prestige as

- 7. The reasons for the defeat of LatinThe

- 8. The increase in national feeling (XV-XVI c.)

- 9. But, while English was thus

- 10. Principal Quantitative Changeslengthening before –ss, -st,

- 11. b) Shortening before [ɵ, d, t,k]When ME

- 12. The Great Vowel Shift (15-late 17th c.)the

- 13. The changes were “independent” and effected regularly

- 15. Rounding of vowels after /w / (18th

- 16. NE Consonant System Vocalisation of [r] =

- 17. the cluster [er] changed to [ar]: e.g.

- 18. The vocalisation of [r] took place in

- 19. 2) lengthening Sometimes the only trace left

- 20. If [ə] produced by vocalisation of [r]

- 22. Early Modern English GrammarIn morphology the trend

- 23. Nounsthe –es of plurals and Gen Sg.

- 24. Personal pronouns:new forms arose: it and its;the

- 25. The inflectional system of the verb underwent

- 26. Adjectives lost all endings except for in the comparative and superlative forms.

- 27. Скачать презентацию

- 28. Похожие презентации

I. Historical background to the New StandardII. NE Vowel System:Quantitative changes;The Great Vowel Shift;Development of ME short vowels;

![Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4) b) Shortening before [ɵ, d, t,k]When ME ē was shortened before [ɵ,d,t,k],](/img/tmb/15/1458591/ab25552424590e2bfa563ede2473df21-720x.jpg)

![Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4) NE Consonant System Vocalisation of [r] = the weakening of [r]The sonorant](/img/tmb/15/1458591/10ed0f26c27104145abc942958aede9a-720x.jpg)

![Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4) the cluster [er] changed to [ar]: e.g. OE deorc – Early ME](/img/tmb/15/1458591/5179e8616f1d335db844322c2e972a5b-720x.jpg)

![Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4) The vocalisation of [r] took place in the 16th or 17th c.](/img/tmb/15/1458591/159b3ff2f202c5d4fb6da89642a465ff-720x.jpg)

![Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4) 2) lengthening Sometimes the only trace left by the loss of [r]](/img/tmb/15/1458591/890bb33d2c619f8e2aa6e0ae45329f46-720x.jpg)

![Early modern english phonological and morphological system. (Lecture 4) If [ə] produced by vocalisation of [r] was preceded by a diphthong,](/img/tmb/15/1458591/b379f27a974063f68df115fd7c0e2326-720x.jpg)

Слайд 4

1476 Caxton introduced the printing press to England;

1492

Columbus reached the ‘new World’;

By 1500, the English language

was such that native speakers of Modern English generally need no translations to understand it. Слайд 5 The late Middle Ages (14th c.) had seen

the triumph of the English language over French, and

the establishment of a standard form of written English.A standard laguage is a taught language which each individual has to learn whatever his or her own pronunciation.

Слайд 6 Nonetheless Latin still had great prestige as the

language of international learning;

the three greatest scientific works published

by Englishmen between 1600 and 1700 were all in Latin: Gilbert’s book on magnetism (1600), Harvey’s on the circulation of the blood (1628), and Newton’s Principia (1689).

Слайд 7

The reasons for the defeat of Latin

The Reformation

period (the establishment of Protestantism, VI-VII c.). The translation

of the Bible into English, and the changeover from Latin to English in church services, raised the prestige of English. The more extreme Protestants regarded Latin as a “Popish” language, designed to keep ordinary people in ignorance and to maintain the power of priests.Слайд 8 The increase in national feeling (XV-XVI c.) that

led to a great interest and pride in the

national language.The rise of social and occupational groups (skilled craftsmen, explorers, soldiers) which were eager to read and to learn in English. The spread of literacy among them.

Слайд 9 But, while English was thus establishing

its supremacy over Latin, it was at the same

time more under its influence:the introduction of Latin loan-words into English, e.g. vacuum, area, radius;

many words borrowed from French were given a Latin dress, e.g. NE debt and doubt (cf. Lat. debitum and dubitare).

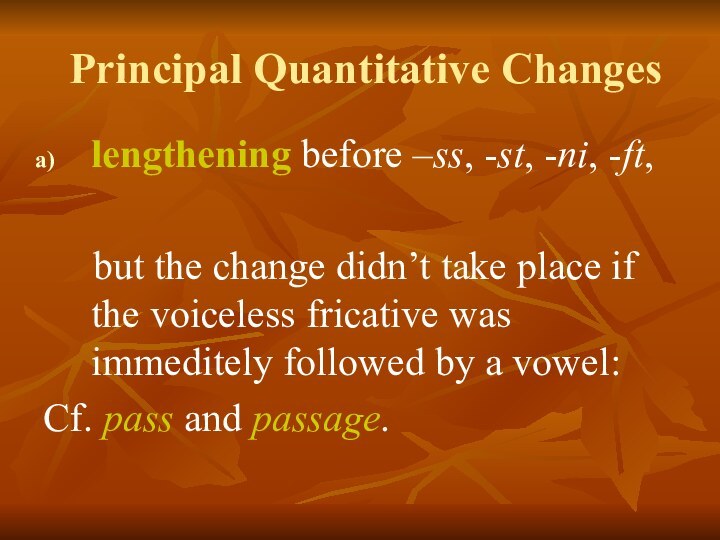

Слайд 10

Principal Quantitative Changes

lengthening before –ss, -st, -ni,

-ft,

but the

change didn’t take place if the voiceless fricative was immeditely followed by a vowel: Cf. pass and passage.

Слайд 11

b) Shortening before [ɵ, d, t,k]

When ME ē

was shortened before [ɵ,d,t,k], it became [ɛ], as in

breath, bread, sweat.When ME ō was shortened before [k,t], it became [ʊ], as in look and foot.

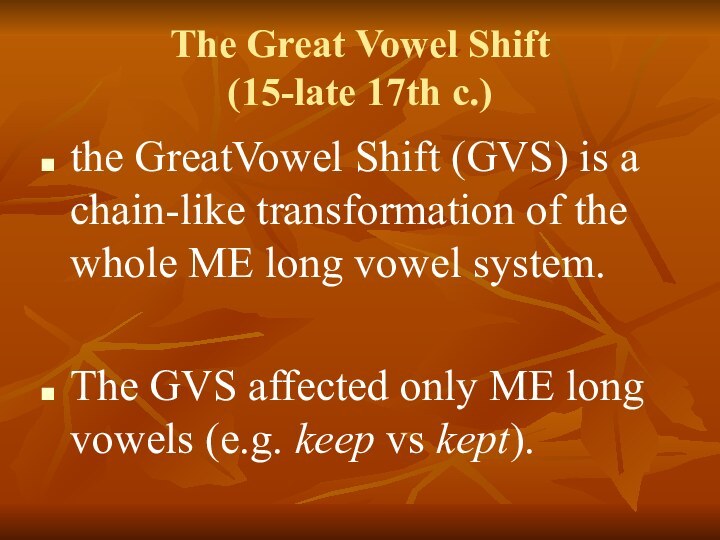

Слайд 12

The Great Vowel Shift

(15-late 17th c.)

the GreatVowel Shift

(GVS) is a chain-like transformation of the whole ME

long vowel system.The GVS affected only ME long vowels (e.g. keep vs kept).

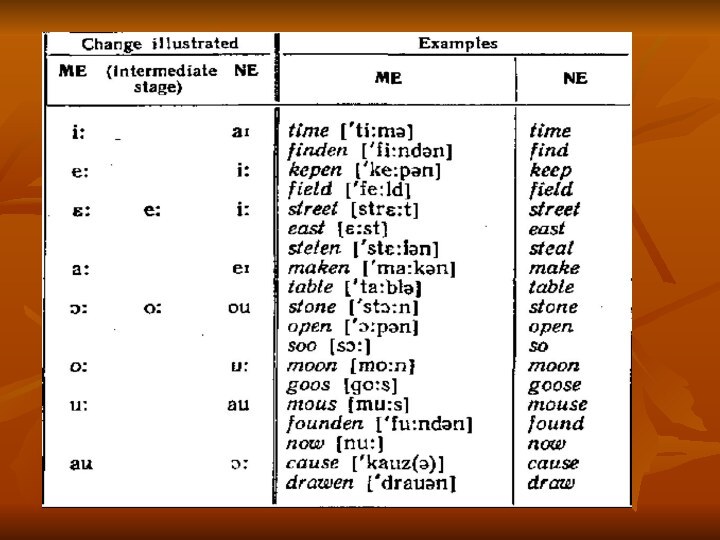

Слайд 13 The changes were “independent” and effected regularly any

stressed vowel in any position.

The GVS didn’t add any

new sounds to the vowel system. Thus, the modification of the words under the GVS was not reflect in their written forms.

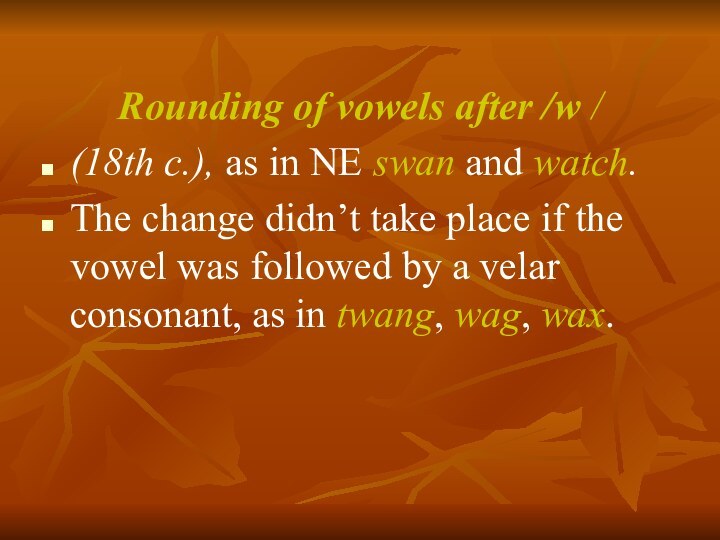

Слайд 15

Rounding of vowels after /w /

(18th c.),

as in NE swan and watch.

The change didn’t

take place if the vowel was followed by a velar consonant, as in twang, wag, wax.Слайд 16 NE Consonant System Vocalisation of [r] = the weakening

of [r]

The sonorant [r] began to produce a certain

influence upon the preceding vowels in Late ME. [r] made the preceding vowel more open and retracted:

Слайд 17

the cluster [er] changed to [ar]: e.g. OE

deorc – Early ME derk – Late ME dark;

although

the change of [er] to [ar] was fairly common, it didn’t affect all the words with the given sounds: cf. ME servent, person.Слайд 18 The vocalisation of [r] took place in the

16th or 17th c.

1) diphthongization.

In Early NE [r] was vocalised when stood after vowels, either finally or followed by another consonant. Losing its consonant character [r] changed into [ə], which was added to the preceding vowel as a glide to form a diphthong: e.g. ME there [ɵɛ:re] NE there.

Слайд 19

2) lengthening

Sometimes the only trace left by

the loss of [r] was the compensatory lengthening of

the preceding vowel: e.g. ME arm [arm] – NE arm.3) change of quality

under the influence of [r], vowels [e, i,u] became [ə]

In the final unstressed position: ME ridere – NE rider.

Слайд 20 If [ə] produced by vocalisation of [r] was

preceded by a diphthong, it was added to the

diphthong to form a triphthong: e.g. ME shour [ʃu:r] – NE shower.[r] was not vocalised when doubled after consonants and initially: e.g. NE errand, dry, read.

This process didn’t take place in all varieties of English. Those varietes in which it was retained are called rhotic, (cf. non-rhotic)

Слайд 22

Early Modern English Grammar

In morphology the trend towards

simplification continues.

EME is characterized by an increase in

the number of prepositions and auxiliaries (grammaticalization), as expected of a languagebecoming more analytic.

Слайд 23

Nouns

the –es of plurals and Gen Sg. was

established;

Plurals in –en and zero plurals are reduced to

their modern extent by the end of the 17th c.;The –es Genitive was interpreted as his and this led to forms like for Christ his sake.

Слайд 24

Personal pronouns:

new forms arose: it and its;

the use

of you with a singular meaning was prompted by

politeness and the influence of French.Demonstrative pronouns:

- this ‘close to the speaker’, that ‘close to the hearer’, yon ‘distant from both speaker and hearer’

Слайд 25 The inflectional system of the verb underwent further

simplification:

in the 3d person the –eth ending is found

in writing until the 17th c., but it is increasingly restricted to poetry. The –s form was already the usual form in speech by the 16th c.;There was a more limited use of the progressive and auxiliary verbs than there is now, however.