Слайд 2

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald was born in St.

Paul, Minnesota on September 24, 1896. His family lived

in a building called the San Mateo Flats in a neighborhood that did not have electricity until 1911.

Two sisters, ages one and three, had died from influenza shortly before his birth. Probably because of this, his mother became overly protective.

Five years later, Fitzgerald’s sister, Annabelle, was born.

Слайд 3

His parents, although poor, had some social status.

Fitzgerald was named after his second cousin, Francis Scott

Key, the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Слайд 4

Fitzgerald grew up in a family of declining

and precarious fortune.

His father, Edward, failed as a

manufacturer of wicker furniture in St. Paul. He became a salesman for Proctor & Gamble, but was dismissed in 1908 when Fitzgerald was twelve years old.

Fitzgerald’s mother, Mollie, helped support the family with her inheritance. They moved to an apartment in this brownstone “row house” in St. Paul, Minnesota, in an area called Summit Terrace, a section of the city inhabited by the city’s wealthiest residents.

Слайд 5

While his family was not prosperous, Fitzgerald’s mother

nurtured social ambitions in her only son. An elderly

aunt helped finance his tuition at a private Catholic boarding school in New Jersey called The Newman School and then, in 1913, at Princeton University.

At the time, Princeton University was viewed as a training ground for the American upper class.

Слайд 6

While his grades were low, he excelled in

his writings for the Princeton Triangle Club Dramatic Society

and the Princeton Tiger. Fitzgerald’s writing from that time shows that he was self-conscious about the differences between himself and his wealthy classmates.

Coming from a background of “financial anxiety,” while at Princeton, Fitzgerald developed a fascination with the very rich.

Слайд 7

In 1917, during his third year at Princeton,

Fitzgerald left school in order to enlist in the

United States Army. After passing a special examination, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the infantry.

Afraid that he might die in the war, Fitzgerald quickly finished a novel he had been working on called The Romantic Egoist. While he received a rejection letter from Charles Scribner’s Sons Publishing Co., the novel’s originality was praised. He was encouraged to resubmit the novel after revision.

Слайд 8

In June 1918, while stationed at Camp Sheridan,

near Montgomery, Alabama, twenty-one year old Fitzgerald met and

fell madly in love with eighteen-year-old Zelda Sayre. She was a local debutante, the youngest daughter of an Alabama Supreme Court Judge.

Their romance intensified Fitzgerald’s desire to achieve success with his novel, but after revision, it was rejected a 2nd time.

Fitzgerald had just completed his officer training and was about to embark for France when the Armistice was signed.

Слайд 9

After being discharged from the Army in 1919,

Fitzgerald went to New York to seek his fortune

so that he could marry Zelda. By day, he worked in an advertising agency, and by night, he wrote stories, submitting them to magazines. For his efforts, he collected nothing but rejection slips.

While Fitzgerald was failing financially as a writer, Zelda broke their engagement. She was unwilling to live on his small salary in the advertisement business. Fitzgerald returned to his parents’ house in St. Paul to rewrite his novel, changing the title to This Side of Paradise.

Слайд 10

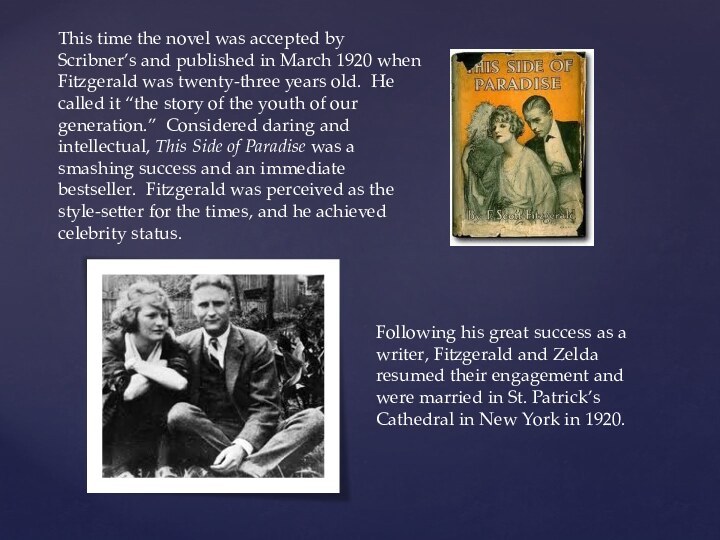

This time the novel was accepted by Scribner’s

and published in March 1920 when Fitzgerald was twenty-three

years old. He called it “the story of the youth of our generation.” Considered daring and intellectual, This Side of Paradise was a smashing success and an immediate bestseller. Fitzgerald was perceived as the style-setter for the times, and he achieved celebrity status.

Following his great success as a writer, Fitzgerald and Zelda resumed their engagement and were married in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in 1920.

Слайд 11

Their only child, a daughter named Frances Scott

(Scottie) Fitzgerald, was born in October 1921.

Слайд 12

Fitzgerald’s life in the 1920s was a mirror

to events occurring nationally during that decade. The Roaring

Twenties, also commonly referred to as The Jazz Age, was a time of challenge to the established order, of personal indulgence, and even self-destructive excess. Fitzgerald was its self-proclaimed spokesman and symbol.

Слайд 13

Much has been written about Zelda and her

effect on Fitzgerald’s career. She was an aspiring dancer,

she craved attention, and she had expensive taste. She also suffered from mental illness.

While this was an era of Prohibition, Fitzgerald and Zelda drank alcohol publicly and partied like there was no tomorrow. Their tastes were for life in New York’s luxurious Plaza Hotel, expensive and gigantic cars, country homes on Long Island or in Connecticut, and villas in France.

Слайд 14

They spent money as fast as Fitzgerald could

make it. In fact, they spent more than he

could make, and they found themselves in debt. Fitzgerald was to spend the rest of his life in a futile struggle to make ends meet.

In 1922 Fitzgerald published The Beautiful and the Damned. This novel delineated the self-indulgence and destruction of Anthony and Gloria Patch and was based on the lives of Fitzgerald and Zelda, who were known for their glamorous and “unsettled” lives.

Слайд 15

Two collections of short stories – Flappers and

Philosophers (1920) and Tales of the Jazz Age (1922)

were his next publications. They were judged harshly by critics, motivating Fitzgerald to redirect his efforts.

Fitzgerald made a conscious effort to concentrate on creating serious, even tragic works that addressed broad historical and social issues.

Fitzgerald’s new sense of vocation, his greater personal maturity, his increasingly complex sense of his era’s place in world history, and his growing awareness of the technical and stylistic capabilities of the modern novel resulted in The Great Gatsby.

Слайд 16

Published in 1925, The Great Gatsby is frequently

nominated as “the great American novel.”

A quintessential story

of not only the 1920s , but also of the American experience, the novel chronicles the exuberance, as well as the malaise of the decade, showing how America’s fascination with material success was eroding values.

The novel received critical praise, but sales were mediocre. Many attribute this to the difficulty Scribner’s had marketing the novel. Is it a romance? Is it a satire?

The fact that the novel did not sell well was a disappointment from which Fitzgerald never recovered.

Слайд 17

Life in the second half of the 1920s

became desperate for the Fitzgeralds. As the Jazz Age

drew to its traumatic close with the stock market crash of 1929, so did much of Fitzgerald’s life and career.

An alcoholic since age 22, Fitzgerald’s drinking got out of control, earning him the dubious title, “America’s Drunkest Writer.”

Слайд 18

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/07/18/f-scott-fitzgerald_n_901641.html

Слайд 19

In 1930 Zelda suffered the first of several

complete nervous breakdowns. She spent the last eighteen years

of her life in sanatoriums in Europe and the U.S.

Fitzgerald’s fourth novel, Tender Is the Night, was published in 1934. It tells the story of an American psychiatrist whose promising career is compromised by his wife’s madness. Transparently basing the wife on Zelda, Fitzgerald had once again located a theme on a grand American scale while using the process of writing as catharsis for personal woes.

Released in the midst of the Great Depression, the novel did not sell well, though it had excellent reviews.

Слайд 20

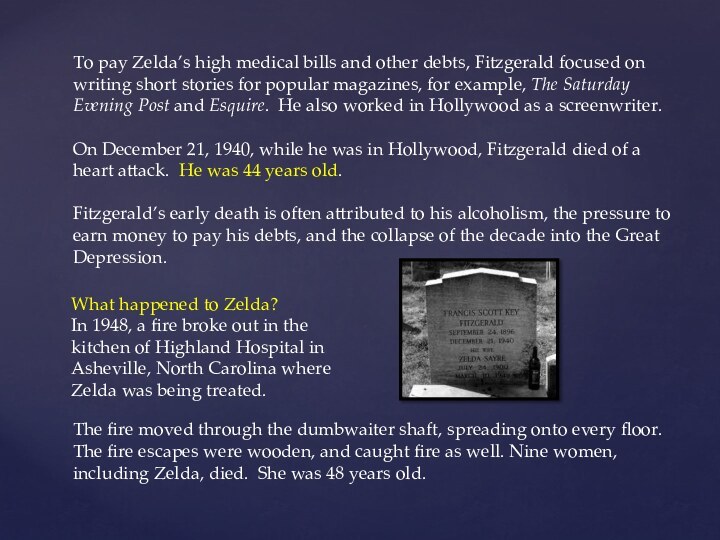

To pay Zelda’s high medical bills and other

debts, Fitzgerald focused on writing short stories for popular

magazines, for example, The Saturday Evening Post and Esquire. He also worked in Hollywood as a screenwriter.

On December 21, 1940, while he was in Hollywood, Fitzgerald died of a heart attack. He was 44 years old.

Fitzgerald’s early death is often attributed to his alcoholism, the pressure to earn money to pay his debts, and the collapse of the decade into the Great Depression.

The fire moved through the dumbwaiter shaft, spreading onto every floor. The fire escapes were wooden, and caught fire as well. Nine women, including Zelda, died. She was 48 years old.

What happened to Zelda?

In 1948, a fire broke out in the kitchen of Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina where Zelda was being treated.

Слайд 21

Fitzgerald and Zelda are buried together in St.

Mary’s Cemetery in Rockville, Maryland.

The last sentence of The

Great Gatsby is inscribed on their grave marker.

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Слайд 22

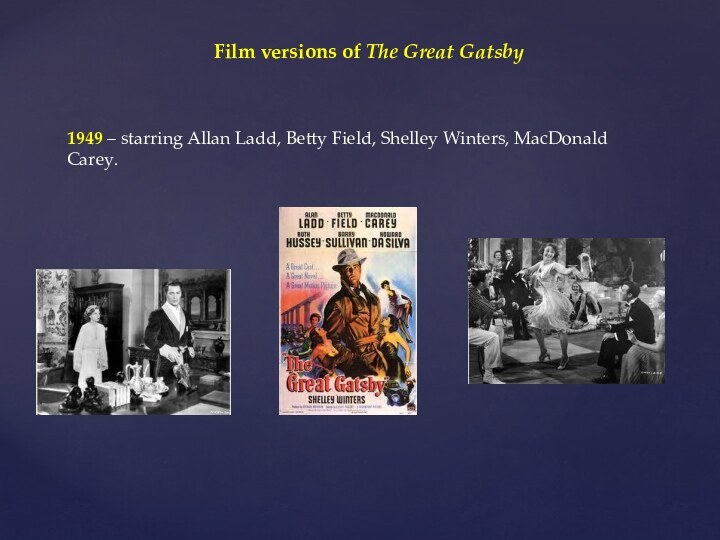

Film versions of The Great Gatsby

1949 – starring

Allan Ladd, Betty Field, Shelley Winters, MacDonald Carey.

Слайд 23

1974 – starring Robert Redford, Mia Farrow, Bruce

Dern, Karen Black, Sam Waterson. Screenplay by Francis Ford

Coppola.

The estimated budget was more than $6 million, and the film won 2 Oscars (Best Costume Design, Best Original Song Score)

Слайд 24

1995 – A&E made-for-TV movie starring Mira Sorvino,

Toby Stevens, Paul Rudd.

Слайд 25

2012 – (set for release Dec. 21) starring

Leonardo DiCaprio, Carey Mulligan, Tobey McGuire, Isla Fisher. There

are rumors that the movie will be 3D.

Слайд 26

The Great Gatsby Trivia

A commercial flop!

The Great Gatsby

did not result in a great pay day for

Fitzgerald. Eleven years after its publication, Fitzgerald estimated the novel had sold less than 25,000 copies in the U.S. Fitzgerald’s last royalty statement reported sales of 7 copies of Gatsby in the first half of 1940.

Free copies for soldiers!

During WWII , Scribner’s published 150,000 complimentary copies to send to men fighting in the war.

Twenty years later . . . a success!

By 1945, The Great Gatsby was #8 on Bantam Publishing Co.’s top ten titles. Today Gatsby is one of the best-selling novels ever; more than ten million copies have been printed. Gatsby regularly produces more than $500,000 a year in a trust for Fitzgerald’s grandchildren.

Слайд 27

Francis Cugat’s jacket design for The Great Gatsby

is the most celebrated and widely disseminated jacket art

in American Literature. After appearing on the first printing in 1925, it was revived more than a half-century later for the “Scribner Library” paperback editions (1979 – present).

Cugat’s painting is iconic: the sad, hypnotic, heavily outlined eyes of a woman beam like headlights through a cobalt night sky. Their irises are transfigured into reclining female nudes. From one of the eyes streams a green luminescent tear; brightly rouged lips complete the sensual triangle. Below, on earth, brightly colored carnival lights blaze before a metropolitan skyline.