- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Icons and icon painting in Ukraine

Содержание

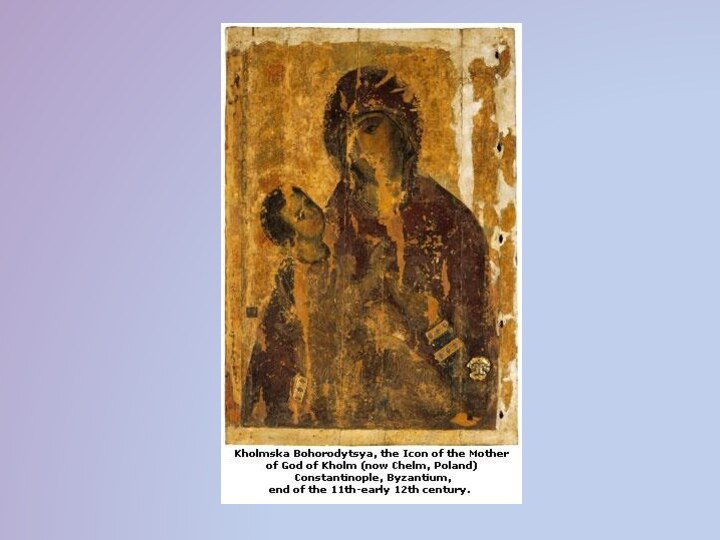

- 2. Icons came to Ukraine, or rather to

- 4. An icon is a painted image of

- 5. During the early Christian period, after the

- 6. Archangel Michael. From the Church of ParaskevaPyatnytsya

- 7. Orthodox Christians usually say their prayers in

- 8. Christianity teaches that the immaterial God became

- 9. In the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy, and

- 10. Diesis. From the Church of Pokrova Bohorodytsiin the village of Richytsya, Rivne Oblast.Late 15th-early 16th century.

- 11. Color too plays an important role. Gold

- 12. Letters are symbols too. Most icons incorporate

- 13. St Basil the Great.From the village of Turye, Lviv Oblast. 15th century.

- 14. The Eastern Church formulated the doctrinal basis

- 15. St Boris and St Hleb.From the Church

- 16. The Eastern Orthodox view of the origin

- 17. Crucifixion. From the Church of Archangel Michaelin

- 18. Eastern Orthodox believers find the first instance

- 19. Virgin Mary from the Diesis (detail), by

- 20. Ukrayinska ikona 11–18 stolit albom is the

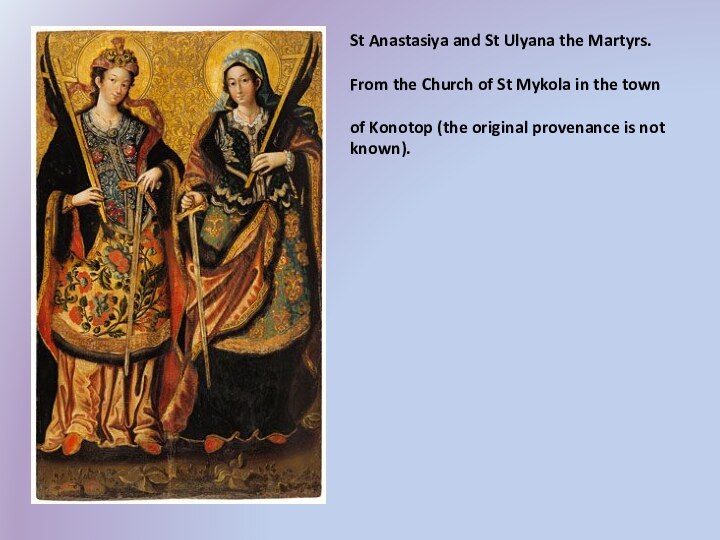

- 21. St Anastasiya and St Ulyana the Martyrs.From

- 22. Скачать презентацию

- 23. Похожие презентации

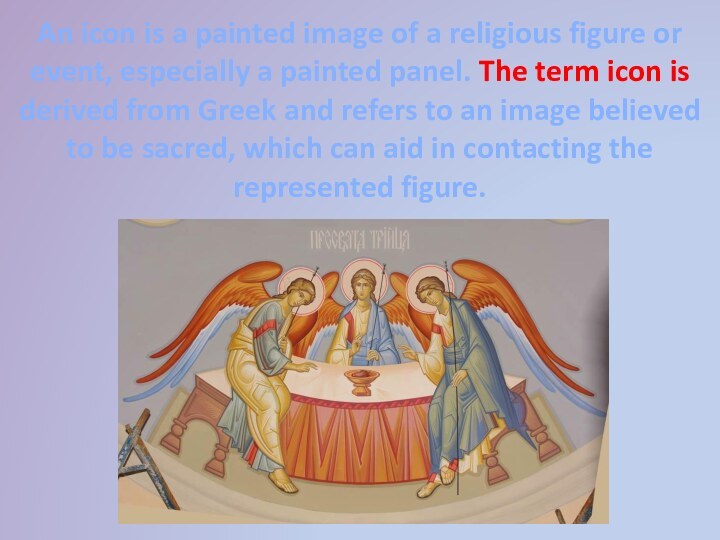

Слайд 4 An icon is a painted image of a

religious figure or event, especially a painted panel. The

term icon is derived from Greek and refers to an image believed to be sacred, which can aid in contacting the represented figure.Слайд 5 During the early Christian period, after the 4th

century, the term was applied to all religious art,

including mosaics, reliefs and paintings. Few early painted icons survive, but a small group of 6th and 7th century encaustic (wax) paintings on wooden panels, from the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai, show realistic, lifelike faces animated by large eyes and intense expressions. Four such icons are in the possession of the Khanenko Museum in Kyiv. Icons were made for private devotion and public worship.

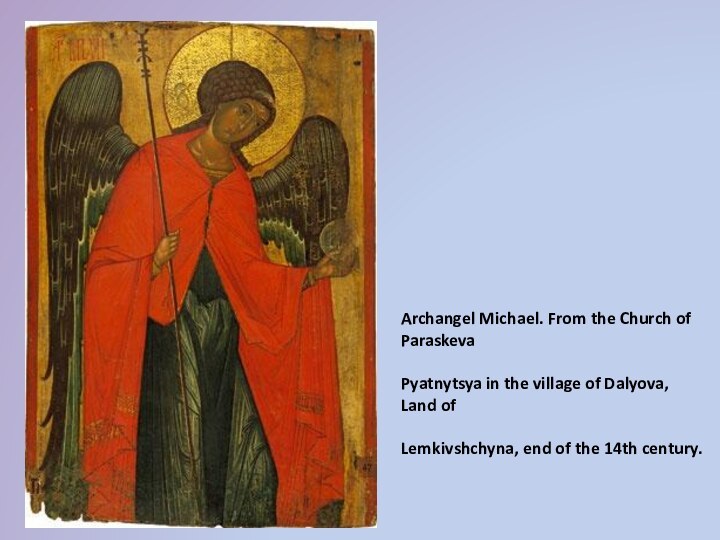

Слайд 6

Archangel Michael. From the Church of Paraskeva

Pyatnytsya in

the village of Dalyova, Land of

Lemkivshchyna, end of the

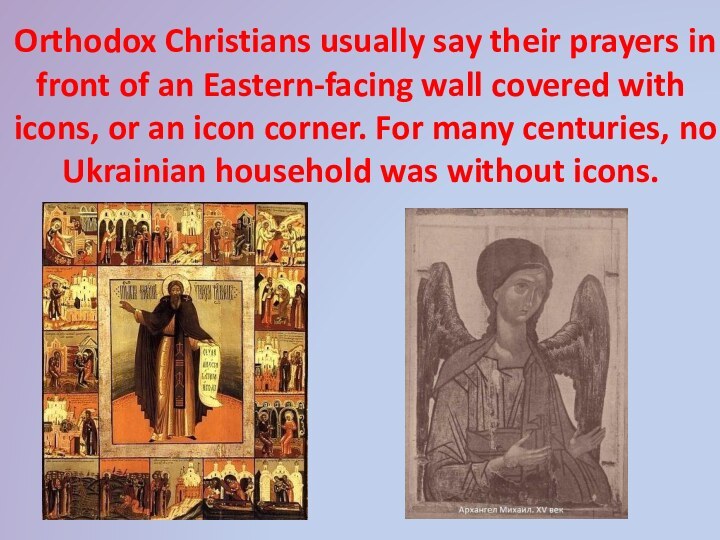

14th century.Слайд 7 Orthodox Christians usually say their prayers in front

of an Eastern-facing wall covered with icons, or an

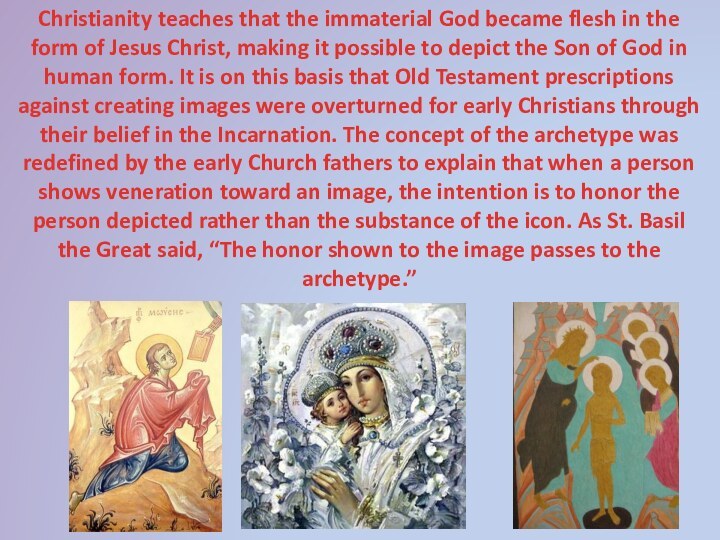

icon corner. For many centuries, no Ukrainian household was without icons.Слайд 8 Christianity teaches that the immaterial God became flesh

in the form of Jesus Christ, making it possible

to depict the Son of God in human form. It is on this basis that Old Testament prescriptions against creating images were overturned for early Christians through their belief in the Incarnation. The concept of the archetype was redefined by the early Church fathers to explain that when a person shows veneration toward an image, the intention is to honor the person depicted rather than the substance of the icon. As St. Basil the Great said, “The honor shown to the image passes to the archetype.”Слайд 9 In the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy, and of

the Early Medieval West, there is very little room

for artistic license. Almost everything within the image has a symbolic aspect. Christ, the saints and angels all have halos. Angels (and often John the Baptist) have wings because they are messengers. Figures have consistent facial appearances, hold attributes personal to them, and use a few conventional poses.

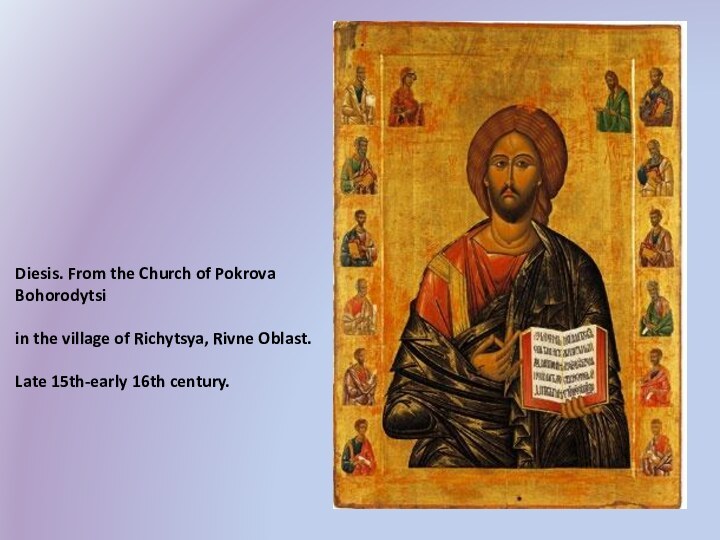

Слайд 10

Diesis. From the Church of Pokrova Bohorodytsi

in the

village of Richytsya, Rivne Oblast.

Late 15th-early 16th century.

Слайд 11 Color too plays an important role. Gold represents

the radiance of Heaven; red, divine life. Blue is

the color of human life, while white is the uncreated essence of God, only used for the resurrection and transfiguration of Christ. If you look at icons of Jesus and Mary, you’ll discover that Jesus usually wears a red undergarment with a blue outer garment (God became human) and Mary wears a blue undergarment with a red over-garment (human became Godlike); thus, the doctrine of deification is conveyed by icons.Annunciation.

From the Church of Paraskeva Pyatnytsya

in the village of Dalyova, Land of Lemkivshchyna,

second half of the 16th century.

Слайд 12 Letters are symbols too. Most icons incorporate some

calligraphic text naming the person or event depicted. Even

this is often presented in a stylized manner (in later Western depictions, much of the symbolism survives, though there is far less consistency).St John the Baptist with Gospels.

From the Church of Archangel Michael in the village

of Yasenytsya Zamkova, Lviv Oblast.

Second half of the 16th century.

Слайд 14 The Eastern Church formulated the doctrinal basis for

the veneration of icons. Since God had assumed material

form in the person of Jesus Christ, he could also be represented in pictures. Icons are considered an essential part of the church and given special liturgical veneration. They also serve as mediums of instruction for the uneducated faithful through the iconostasis. An iconostasis is a large screen that separates the altar from the rest of the church. It is on the iconostasis that painted images of Christ, the Virgin and various saints are grouped. Icons were created with a formalized, deliberately stylized aspect that emphasized otherworldliness rather than human feeling or sentimentality. Gold-leaf backgrounds were common with strongly geometric designs, emphasizing either angularity or long, sinuous curves, being favored.Although icon painters usually remained anonymous, some exceptions are known. The best icons represent the supreme achievement in icon painting, and their work combines spiritual grace and technical excellence in a synthesis that was never again equaled.

Слайд 15

St Boris and St Hleb.

From the Church of

the Holy Spirit in the village of

Potelych, Lviv Oblast.

Second half of the 16th century.Слайд 16 The Eastern Orthodox view of the origin of

icons is quite different from that of secular scholars

and some in contemporary Roman Catholic circles. “The Orthodox Church maintains and teaches that the sacred image has existed from the beginning of Christianity,” Leonid Ouspensky, a Russian theologian, has written.Accounts that some non-Orthodox writers consider legendary are accepted as history within Eastern Orthodoxy, because they are a part of Church tradition. Thus, accounts such as of the miraculous “Image Not Made by Hands,” and the weeping and moving “Mother of God” are accepted as fact.

Eastern Orthodoxy further teaches that a clear understanding of the importance of icons was part of the Church from its very beginning, and has never changed, although explanations of their importance may have developed over time. This is because iconography is rooted in the theology of the Incarnation (Christ being the eikon of God), which didn’t change, though its subsequent clarification within the Church occurred over the period of the first seven Ecumenical Councils. Also, icons served as tools of edification for the illiterate faithful during most of the history of Christendom.

Слайд 17

Crucifixion. From the Church of Archangel Michael

in the

village of Hrabiv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.

Second half of the 16th

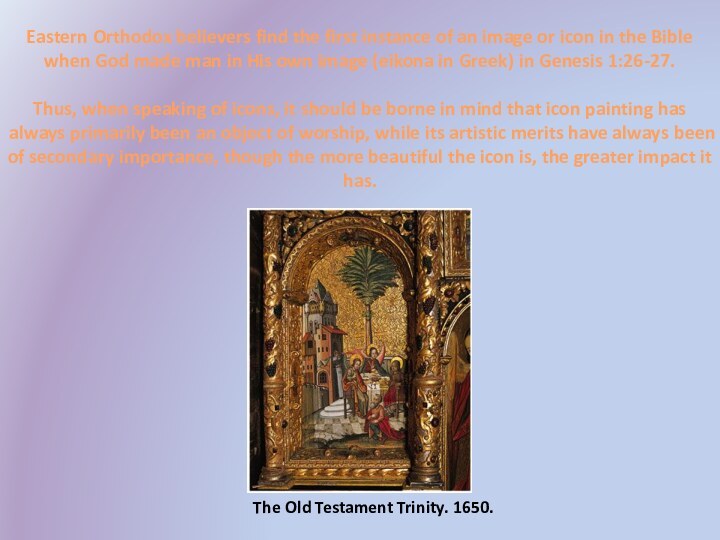

century.Слайд 18 Eastern Orthodox believers find the first instance of

an image or icon in the Bible when God

made man in His own image (eikona in Greek) in Genesis 1:26-27.Thus, when speaking of icons, it should be borne in mind that icon painting has always primarily been an object of worship, while its artistic merits have always been of secondary importance, though the more beautiful the icon is, the greater impact it has.

The Old Testament Trinity. 1650.

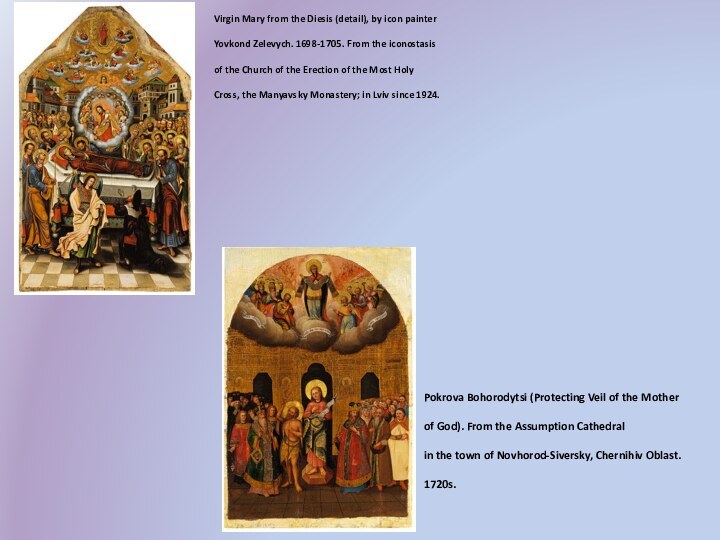

Слайд 19 Virgin Mary from the Diesis (detail), by icon

painter

Yovkond Zelevych. 1698-1705. From the iconostasis

of the Church of

the Erection of the Most HolyCross, the Manyavsky Monastery; in Lviv since 1924.

Pokrova Bohorodytsi (Protecting Veil of the Mother

of God). From the Assumption Cathedral

in the town of Novhorod-Siversky, Chernihiv Oblast.

1720s.

Слайд 20

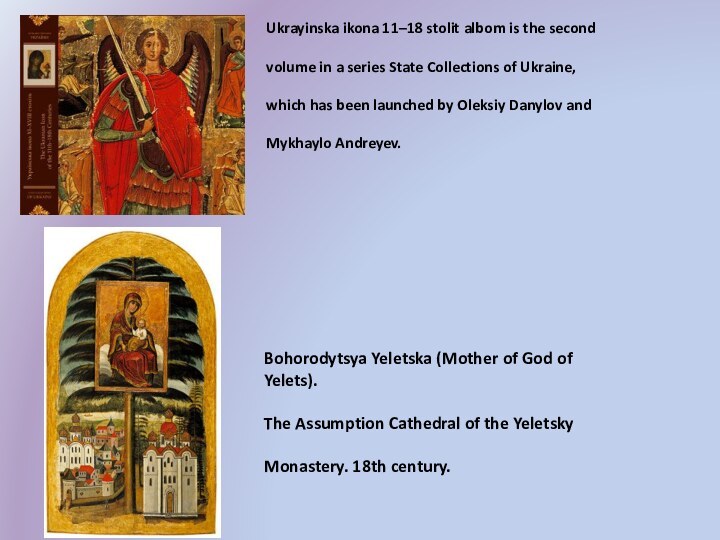

Ukrayinska ikona 11–18 stolit albom is the second

volume

in a series State Collections of Ukraine,

which has been

launched by Oleksiy Danylov andMykhaylo Andreyev.

Bohorodytsya Yeletska (Mother of God of Yelets).

The Assumption Cathedral of the Yeletsky

Monastery. 18th century.