- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Non-discrete effects in language

Содержание

- 2. The problemWe tend to think about language

- 3. Simple example: morpheme fusionдетский det-sk-ij ‘children’s, childish’ Root-Suffix-Ending [deckij] suffix deck-ij root

- 4. Similar exampes abound on all lingustic levelsPhonemes:

- 5. ParadigmaticsThe same problem applies to paradigmatic boundaries,

- 6. SemanticsX said smth (Zaliznjak 2006: 186)‘X uttered

- 7. Diachronic changeRussian писать pisat’ ‘write’Funny slangish use:popisal

- 8. Language contactThe Baltic language Prussian, spoken in

- 9. Intermediate conclusionLanguage simultaneouslylongs for discrete, segmented structuretries

- 10. Possible reactions“Digital” linguistics (de Saussure, Bloomfield, Chomsky...):More

- 11. Cognitive scienceRosch: prototype theoryLakoff: radial categoriesA is

- 12. My main suggestionIn the case of language

- 13. Various kinds of structures▐focal point 1focal point 2 discrete structure▐continuous structurefocal structure1212

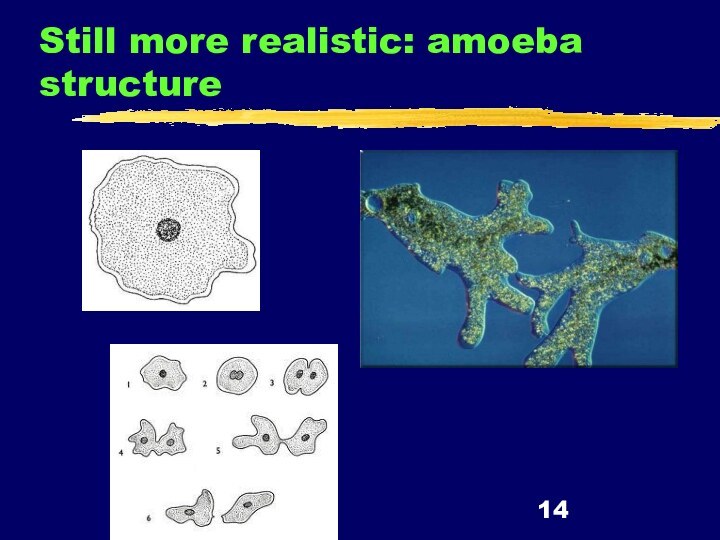

- 14. Still more realistic: amoeba structure

- 15. Examples▐focal point 1focal point 2det sksaid told*pis- pis-Prussian GermanSyntagm.Paradigm.Diachr.Lg.contactetc., etc.

- 16. Peripheral status of non-discrete phenomenaWhere does it

- 17. Kant’s puzzleThe role of observer, or cognizer,

- 18. Recapitulation: A paradoxical state of affairsScience

- 19. What to do?We need to develop a

- 20. 1. Start with prosodyProsody is the aspect

- 21. 2. Explore gesticulationIn addition to sound code,

- 22. 3. Employ mathematics appropriate for the “cognitive

- 23. ConclusionJust as we invoke scientific thinking, we

- 24. Скачать презентацию

- 25. Похожие презентации

The problemWe tend to think about language as a system of discrete elements (phonemes, morphemes, words, sentences)But this view does not survive an encounter with reality

![Non-discrete effects in language Simple example: morpheme fusionдетский det-sk-ij ‘children’s, childish’ Root-Suffix-Ending [deckij] suffix deck-ij root](/img/tmb/11/1067476/1ee69f006c3b831728426136d4aab1f6-720x.jpg)

Слайд 2

The problem

We tend to think about language as

a system of discrete elements (phonemes, morphemes, words, sentences)

this view does not survive an encounter with reality

Слайд 3

Simple example:

morpheme fusion

детский

det-sk-ij ‘children’s, childish’

Root-Suffix-Ending

[deckij]

suffix

deck-ij

root

Слайд 4

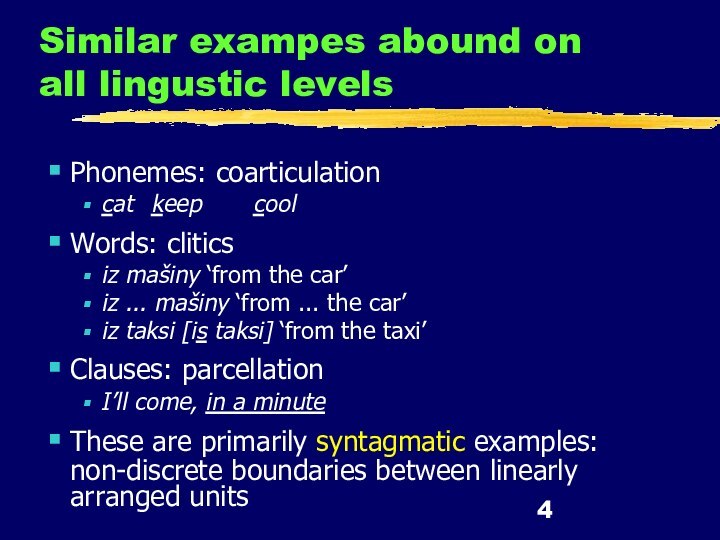

Similar exampes abound on all lingustic levels

Phonemes: coarticulation

cat keep

cool

Words: clitics

iz mašiny ‘from the car’

iz ... mašiny

‘from ... the car’iz taksi [is taksi] ‘from the taxi’

Clauses: parcellation

I’ll come, in a minute

These are primarily syntagmatic examples: non-discrete boundaries between linearly arranged units

Слайд 5

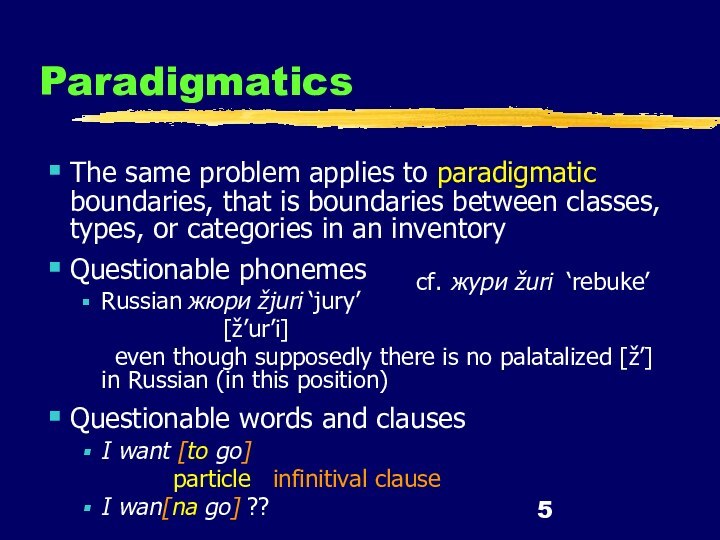

Paradigmatics

The same problem applies to paradigmatic boundaries, that

is boundaries between classes, types, or categories in an

inventoryQuestionable phonemes

Russian жюри žjuri ‘jury’

[ž’ur’i]

even though supposedly there is no palatalized [ž’] in Russian (in this position)

Questionable words and clauses

I want [to go]

particle infinitival clause

I wan[na go] ??

cf. жури žuri ‘rebuke’

Слайд 6

Semantics

X said smth (Zaliznjak 2006: 186)

‘X uttered a

sequence of sounds’

‘X meant smth’

‘X expressed his belief in

smth’‘X wanted Y to know smth’

‘X wanted Y to perform smth’

.................

Some of these meanings are shared by X told smth, but some are not

Слайд 7

Diachronic change

Russian писать pisat’ ‘write’

Funny slangish use:

popisal nozhom

‘cut/slashed someone with a knife’, lit. ‘wrote with a

knife’One of the Indo-European etymologies of the root pis- is ‘create image by cutting’

Apparently the ancient meaning of the root, several millennia old, is still present in a marginal usage of the modern verb

Слайд 8

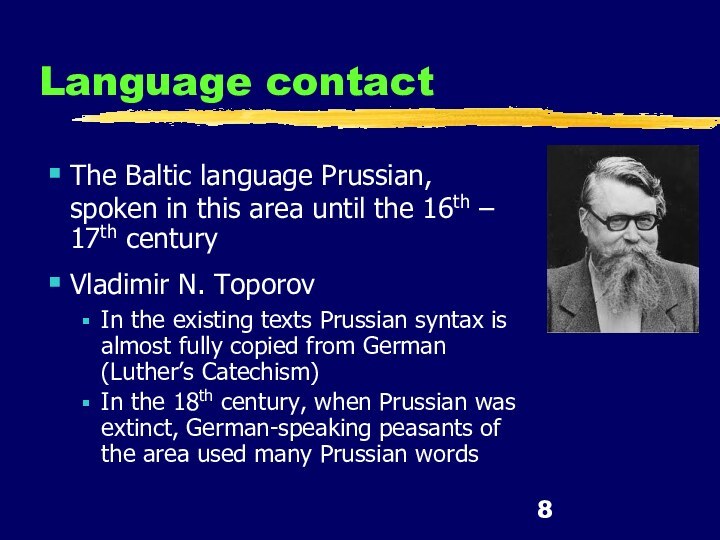

Language contact

The Baltic language Prussian, spoken in this

area until the 16th – 17th century

Vladimir N. Toporov

In

the existing texts Prussian syntax is almost fully copied from German (Luther’s Catechism)In the 18th century, when Prussian was extinct, German-speaking peasants of the area used many Prussian words

Слайд 9

Intermediate conclusion

Language simultaneously

longs for discrete, segmented structure

tries to

avoid it

Non-discrete effects permeate every single aspect of language

This

problem is in the core of theoretical debates about language

Слайд 10

Possible reactions

“Digital” linguistics (de Saussure, Bloomfield, Chomsky...):

More inclusive

(“analog”) linguistics: often a mere statement of continuous boundaries

and countless intermediate/borderline casesignore non-discrete

phenomena or dismiss them

as minor

Ferdinand de Saussure:

language only consists

of identities and differences

the discreteness delusion

a bit too simple-minded

appeal of scientific rigor but extreme reductionism

Слайд 11

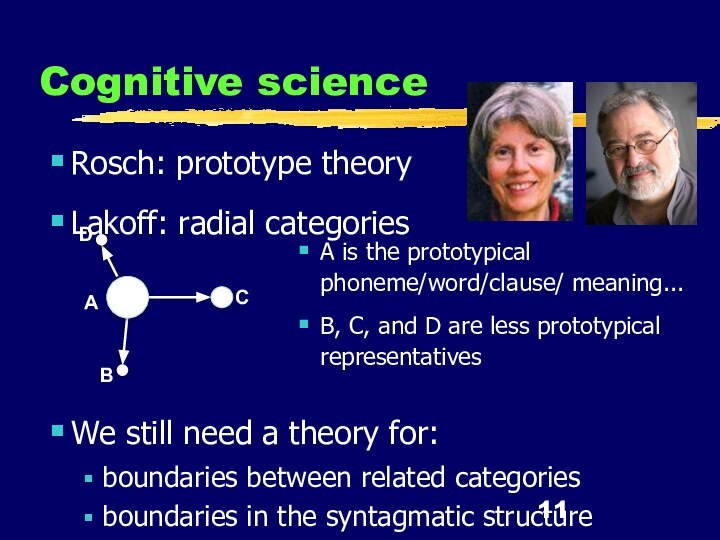

Cognitive science

Rosch: prototype theory

Lakoff: radial categories

A is the

prototypical phoneme/word/clause/ meaning...

B, C, and D are less prototypical

representativesWe still need a theory for:

boundaries between related categories

boundaries in the syntagmatic structure

Слайд 12

My main suggestion

In the case of language we

see the structure that combines the properties of discrete

and non-discrete: focal structureFocal phenomena are simultaneously distinct and related

Focal structure is a special kind of structure found in linguistic phenomena, alternative to the discrete structure

It is the hallmark of linguistic and, possibly, cognitive phenomena, in constrast to simpler kinds of matter

Слайд 13

Various kinds of structures

▐

focal point 1

focal point 2

discrete structure

▐

continuous structure

focal structure

1

2

1

2

Слайд 15

Examples

▐

focal point 1

focal point 2

det sk

said told

*pis- pis-

Prussian German

Syntagm.

Paradigm.

Diachr.

Lg.contact

etc., etc.

Слайд 16

Peripheral status of non-discrete phenomena

Where does it stem

from?

Objective properties of language?

I don’t think so

Or, perhaps, properties

of the observing human mind?This directly relates to one of the key issues in The Critique of Pure Reason

Слайд 17

Kant’s puzzle

The role of observer, or cognizer, crucially

affects the knowledge of the world

“The schematicism by which

our understanding deals with the phenomenal world ... is a skill so deeply hidden in the human soul that we shall hardly guess the secret trick that Nature here employs.”NB: Standards of scientific thought have developed on the basis of physical, rather than cognitive, reality

Physical reality is much more prone to the discrete approach

Compared to physical world, in the case of language and other cognitive processes Kant’s problem is much more acute

because mind here functions both as an observer and an object of observation, so making the distinction between the two is difficult

Слайд 18

Recapitulation:

A paradoxical state of affairs

Science is based

on categorization (Aristotelian, “rationality”, “left-hemispheric”, etc.)

The scientific approach is

inherently biased to noticing only the fitting phenomenaIt is like eyeglasses filtering out a part of reality

Addressing another part of it is perceived as pseudo-science, or quasi-science at best

Language is unknowable, a Ding an sich?

Слайд 19

What to do?

We need to develop a more

embracing linguistics and cognitive science that address non-discrete phenomena:

not

as exceptions or periphery of language and cognition but rather as their core

Can we outwit our mind?

Several avenues towards this goal

Слайд 20

1. Start with prosody

Prosody is the aspect of

sound code

that is obviously non-discrete

Example: Sandro V. Kodzasov’s

analysis of formal quantity

iconically depicting mental quantityIt was lo-ong ago. Oh, tha-at’s the reason.

He just left. That’s clear.

Develop new approaches on the basis of prosody, then apply them to traditional, “segmental” language

Слайд 21

2. Explore gesticulation

In addition to sound code, there

is a visual code:

gesticulation and generally “body language”

Michael

Tomasello: in order to “understand how

humans communicate with one another using a

language <…> we must first understand how

humans communicate with one another using natural gestures”Когда он ехал по дорóге, он поравнялся с дéвочкой,

(From the materials of Julia Nikolaeva)

Simultaneously: iconic gestures and pointing gestures

Слайд 22

3. Employ mathematics appropriate for the “cognitive matter”

Methodological

point

1960s: a fashion of “mathematical methods” in linguistics

This did

not bring much fruit, primarily because of the non-discreteness effectsTime for another attempt of bringing in more useful kinds of mathematics

Ongoing project: study of non-categorical referential choice

When we mention a person/object, we choose from a set of options, such as a proper name (Kant), a common name (the philosopher), or a reduced form (he)

This choice is not always deterministic: sometimes both Kant and he are appropriate

Probabilistic modelling and machine learning techniques used to simulate human behavior in non-categorical situations

Слайд 23

Conclusion

Just as we invoke scientific thinking, we tend

to immediately turn to discrete analysis

This is why discrete

linguistics is so popular, in spite of the omnipresence and obviousness of non-discrete effectsThis may be our inherent bias, or a habit developed in natural sciences, or a cultural preference

But in the case of language and other cognitive processes we do see the limits of the traditional discrete approach

It remains an open question if cognitive scientists are able to eventually overcome the strong bias towards “pure reason” and discrete analysis, or language will remain a Ding an sich

But it is worth trying to circumvent this bias and to seriously explore the focal, non-discrete structure that is in the very core of language and cognition