Слайд 2

All materials are licensed under a Creative Commons

“Share Alike” license.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Attribution condition: You must indicate that derivative

work

"Is derived from John Butterworth & Xeno Kovah’s ’Advanced Intel x86: BIOS and SMM’ class posted at http://opensecuritytraining.info/IntroBIOS.html”

Слайд 3

Reset Vector

Execution Environment

Слайд 4

Real-Address Mode (Real Mode)

The original x86 operating mode

Referred

to as “Real Mode” for short

Introduced way back in

8086/8088 processors

Was the only operating mode until Protected Mode (with its "virtual addresses") was introduced in the Intel 286

Exists today solely for compatibility so that code written for 8086 will still run on a modern processor

Someday processors will boot into protected mode instead

In the BIOS’ I have looked at, the general theme seems to be to get out of Real Mode as fast as possible

Therefore we won’t stay here long either

Слайд 5

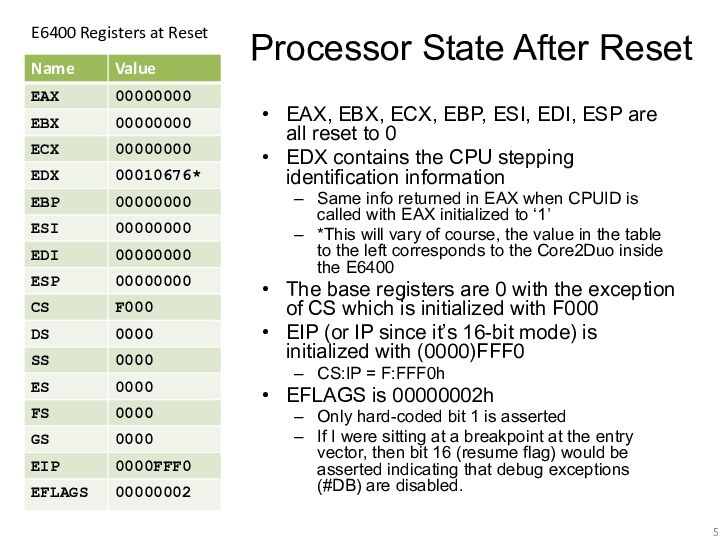

Processor State After Reset

EAX, EBX, ECX, EBP, ESI,

EDI, ESP are all reset to 0

EDX contains the

CPU stepping identification information

Same info returned in EAX when CPUID is called with EAX initialized to ‘1’

*This will vary of course, the value in the table to the left corresponds to the Core2Duo inside the E6400

The base registers are 0 with the exception of CS which is initialized with F000

EIP (or IP since it’s 16-bit mode) is initialized with (0000)FFF0

CS:IP = F:FFF0h

EFLAGS is 00000002h

Only hard-coded bit 1 is asserted

If I were sitting at a breakpoint at the entry vector, then bit 16 (resume flag) would be asserted indicating that debug exceptions (#DB) are disabled.

E6400 Registers at Reset

Слайд 6

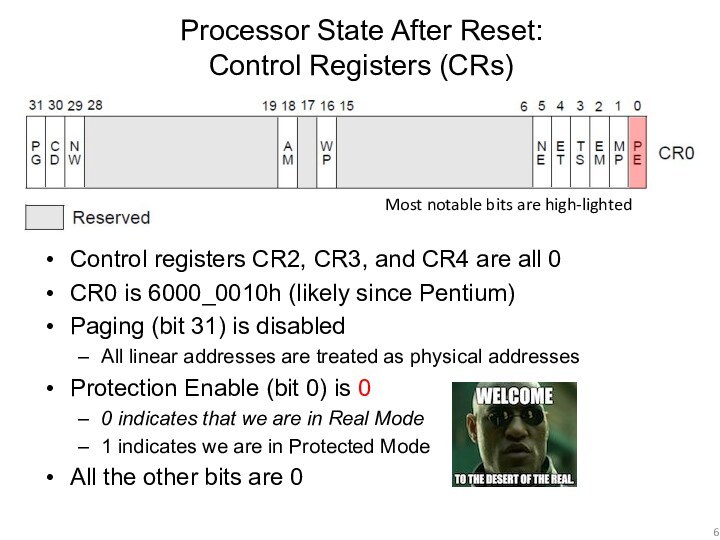

Control registers CR2, CR3, and CR4 are all

0

CR0 is 6000_0010h (likely since Pentium)

Paging (bit 31)

is disabled

All linear addresses are treated as physical addresses

Protection Enable (bit 0) is 0

0 indicates that we are in Real Mode

1 indicates we are in Protected Mode

All the other bits are 0

Most notable bits are high-lighted

Processor State After Reset:

Control Registers (CRs)

Слайд 7

Reset Vector

System Memory

BIOS Flash Chip

0

4GB

www.intel.com/.../datasheet/io-controller-hub-9-datasheet.pdf

0xFFFFFFF0

LPC I/F

At system reset,

the an initial (“bootstrap”) processor begins execution at the

reset vector

The reset vector is always located on flash at "memory" address FFFF_FFF0h

The whole chip is mapped to memory but not all of it is readable due to protections on the flash device itself

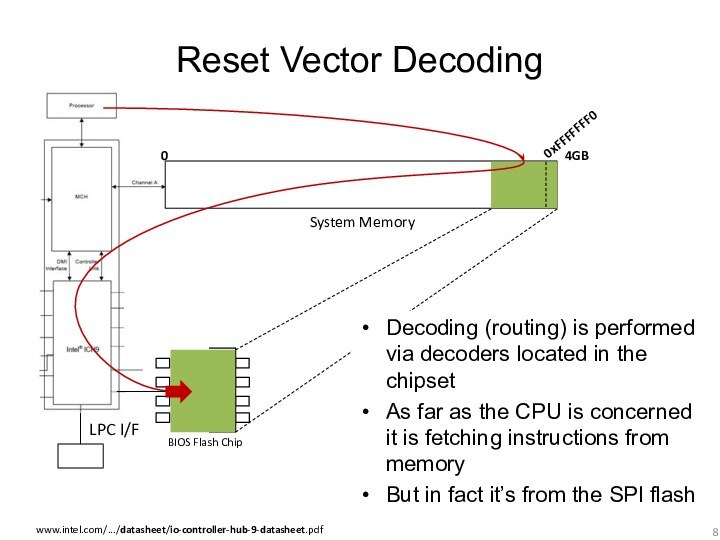

Слайд 8

Reset Vector Decoding

System Memory

BIOS Flash Chip

0

4GB

www.intel.com/.../datasheet/io-controller-hub-9-datasheet.pdf

0xFFFFFFF0

LPC I/F

Decoding (routing)

is performed via decoders located in the chipset

As far

as the CPU is concerned it is fetching instructions from memory

But in fact it’s from the SPI flash

Слайд 9

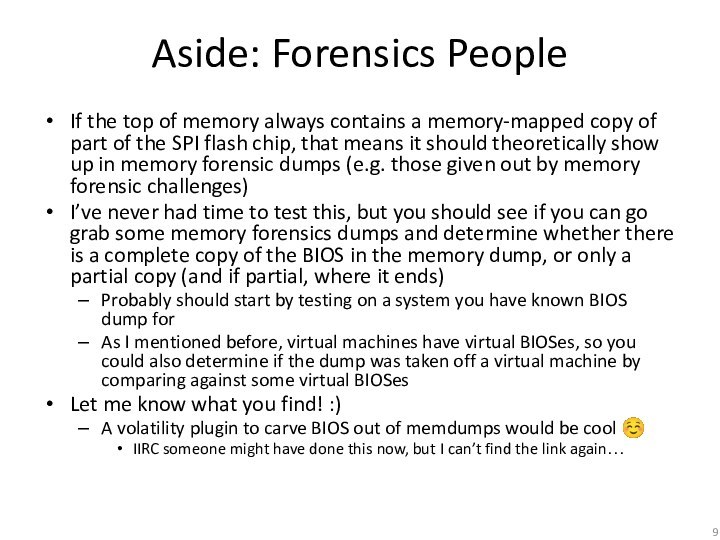

Aside: Forensics People

If the top of memory always

contains a memory-mapped copy of part of the SPI

flash chip, that means it should theoretically show up in memory forensic dumps (e.g. those given out by memory forensic challenges)

I’ve never had time to test this, but you should see if you can go grab some memory forensics dumps and determine whether there is a complete copy of the BIOS in the memory dump, or only a partial copy (and if partial, where it ends)

Probably should start by testing on a system you have known BIOS dump for

As I mentioned before, virtual machines have virtual BIOSes, so you could also determine if the dump was taken off a virtual machine by comparing against some virtual BIOSes

Let me know what you find! :)

A volatility plugin to carve BIOS out of memdumps would be cool ☺

IIRC someone might have done this now, but I can’t find the link again…

Слайд 10

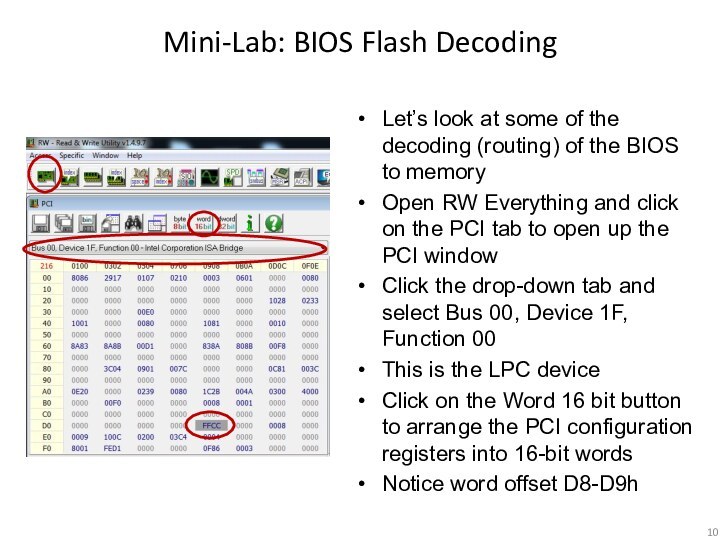

Let’s look at some of the decoding (routing)

of the BIOS to memory

Open RW Everything and click

on the PCI tab to open up the PCI window

Click the drop-down tab and select Bus 00, Device 1F, Function 00

This is the LPC device

Click on the Word 16 bit button to arrange the PCI configuration registers into 16-bit words

Notice word offset D8-D9h

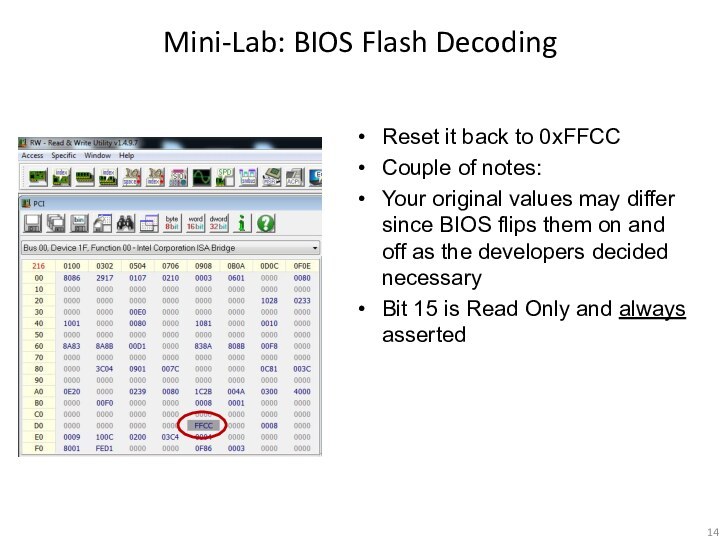

Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding

Слайд 11

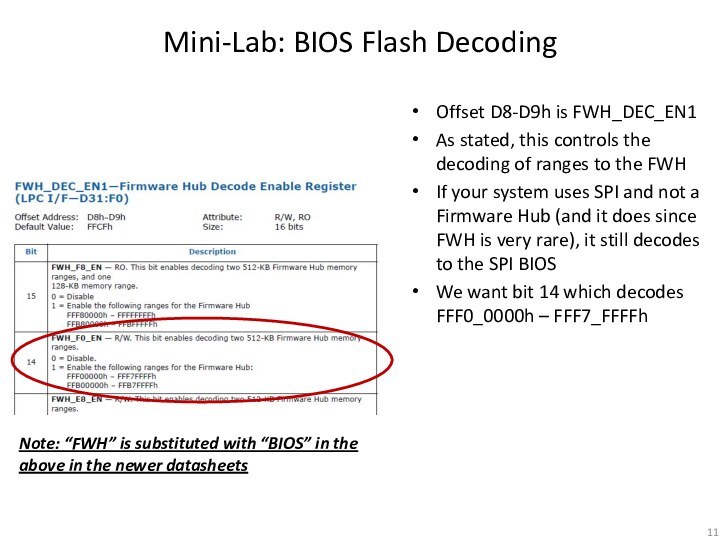

Offset D8-D9h is FWH_DEC_EN1

As stated, this controls the

decoding of ranges to the FWH

If your system uses

SPI and not a Firmware Hub (and it does since FWH is very rare), it still decodes to the SPI BIOS

We want bit 14 which decodes FFF0_0000h – FFF7_FFFFh

Note: “FWH” is substituted with “BIOS” in the above in the newer datasheets

Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding

Слайд 12

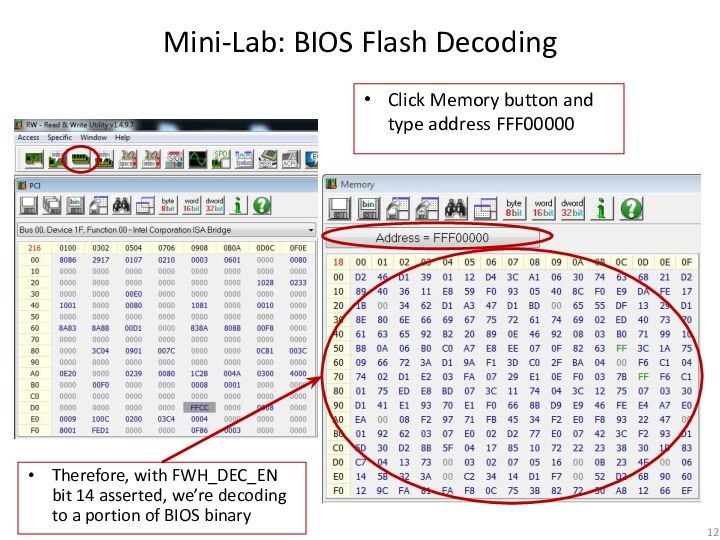

Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding

Therefore, with FWH_DEC_EN bit 14

asserted, we’re decoding to a portion of BIOS binary

Click

Memory button and type address FFF00000

Слайд 13

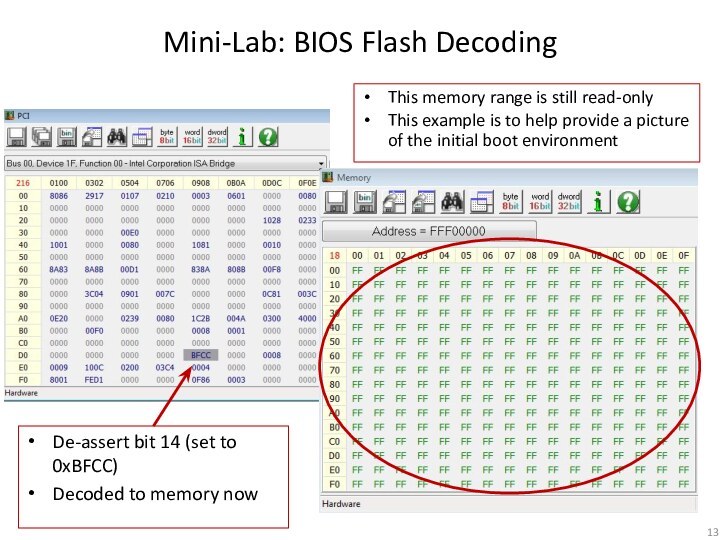

De-assert bit 14 (set to 0xBFCC)

Decoded to memory

now

This memory range is still read-only

This example is to

help provide a picture of the initial boot environment

Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding

Слайд 14

Reset it back to 0xFFCC

Couple of notes:

Your original

values may differ since BIOS flips them on and

off as the developers decided necessary

Bit 15 is Read Only and always asserted

Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding

Слайд 15

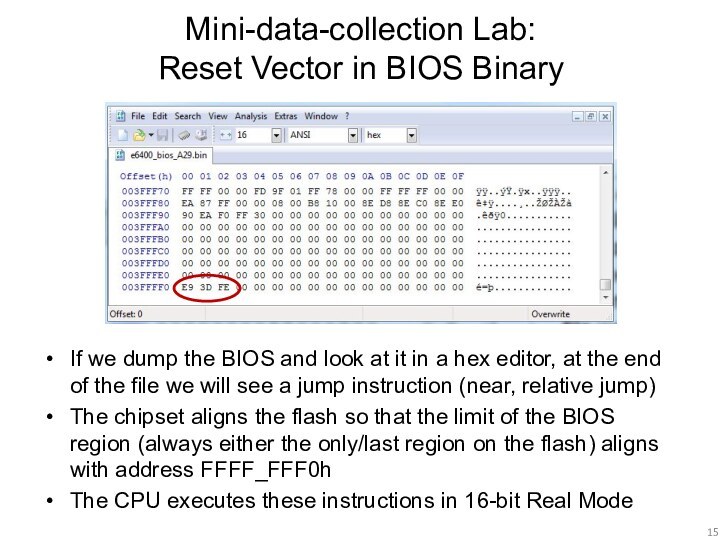

Mini-data-collection Lab:

Reset Vector in BIOS Binary

If we dump

the BIOS and look at it in a hex

editor, at the end of the file we will see a jump instruction (near, relative jump)

The chipset aligns the flash so that the limit of the BIOS region (always either the only/last region on the flash) aligns with address FFFF_FFF0h

The CPU executes these instructions in 16-bit Real Mode

Слайд 16

Real Mode Memory

16-bit operating mode

Segmented memory model

When operating

in real-address mode, the default addressing and operand size

is 16 bits

An address-size override can be used in real-address mode to enable access to 32-bit addressing (like the extended general-purpose registers EAX, EDX, etc.)

However, the maximum allowable 32-bit linear address is still 000F_FFFFH (220 -1)

So how can it address FFFF_FFF0h?

We’ll answer that in a bit

Слайд 17

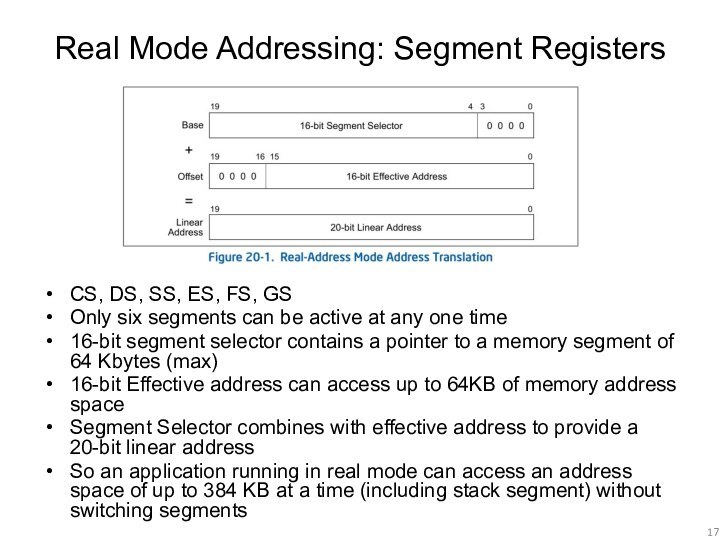

Real Mode Addressing: Segment Registers

CS, DS, SS, ES,

FS, GS

Only six segments can be active at any

one time

16-bit segment selector contains a pointer to a memory segment of 64 Kbytes (max)

16-bit Effective address can access up to 64KB of memory address space

Segment Selector combines with effective address to provide a 20-bit linear address

So an application running in real mode can access an address space of up to 384 KB at a time (including stack segment) without switching segments

Слайд 18

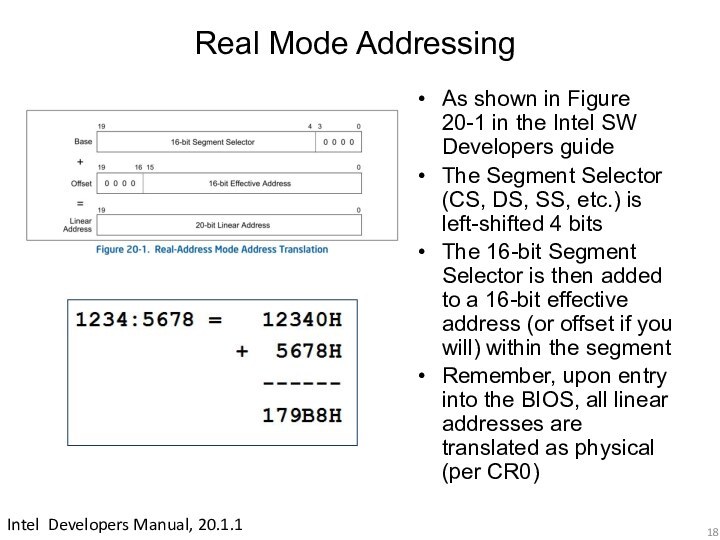

Real Mode Addressing

Intel Developers Manual, 20.1.1

As shown in

Figure 20-1 in the Intel SW Developers guide

The Segment

Selector (CS, DS, SS, etc.) is left-shifted 4 bits

The 16-bit Segment Selector is then added to a 16-bit effective address (or offset if you will) within the segment

Remember, upon entry into the BIOS, all linear addresses are translated as physical (per CR0)

Слайд 19

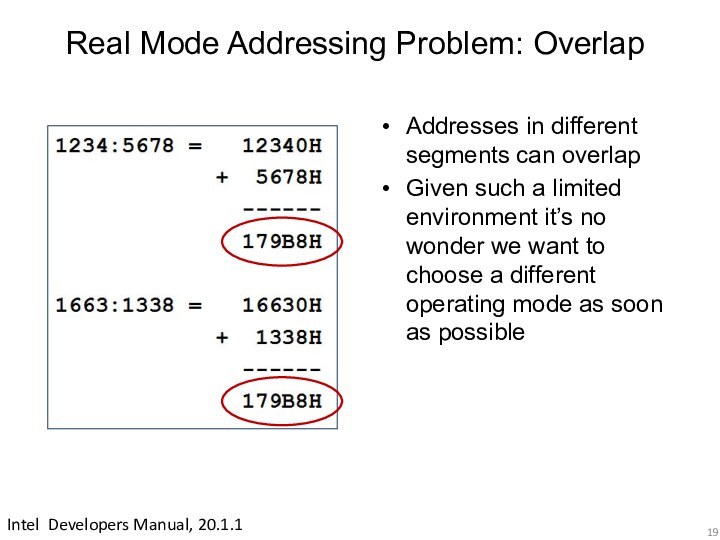

Real Mode Addressing Problem: Overlap

Intel Developers Manual, 20.1.1

Addresses

in different segments can overlap

Given such a limited environment

it’s no wonder we want to choose a different operating mode as soon as possible

Слайд 20

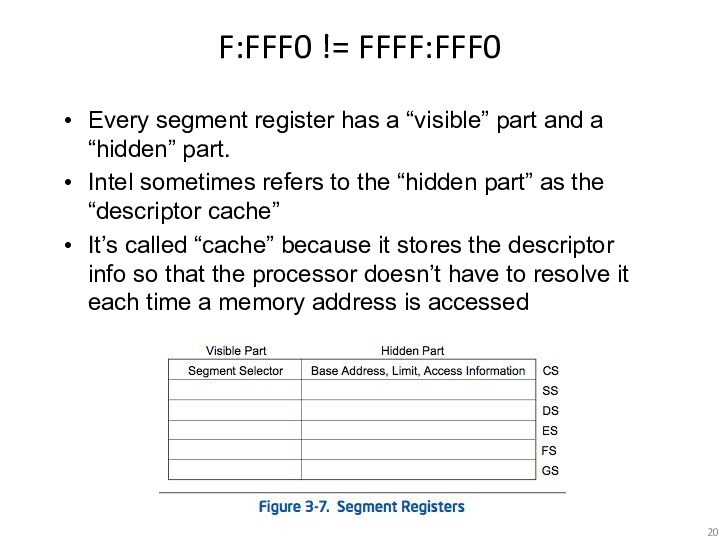

F:FFF0 != FFFF:FFF0

Every segment register has a “visible”

part and a “hidden” part.

Intel sometimes refers to

the “hidden part” as the “descriptor cache”

It’s called “cache” because it stores the descriptor info so that the processor doesn’t have to resolve it each time a memory address is accessed

Слайд 21

Descriptor Cache

“When a segment selector is loaded into

the visible part of a segment register, the processor

also loads the hidden part of the segment register with the base address, segment limit, and [access information] from the segment descriptor pointed to by the segment selector.”

Real Mode doesn’t have protected mode style access-control so the [access information] part is ignored

This means that the hidden part isn’t modified until after a value is loaded into the segment selector

So the moment CS is modified, the CS.BASE of FFFF_0000H is replaced with the new value of CS (left shifted 4 bits)

Intel SW Dev, Vol 3, Sec 3.4.3

Слайд 22

CS.BASE + EIP

CS.BASE is pre-set to FFFF_0000H upon

CPU reset/power-up

EIP set to 0000_FFF0H

So even though CS is

set to F000H, CS.BASE+EIP makes FFFF_FFF0H

So when you see references to CS:IP upon power-up being equal to F:FFF0h, respectively, now you know how what it really means and how it equates to an entry vector at FFFF_FFF0h

Vol. 3, Figure 9-3

Слайд 23

Reset Vector

So upon startup, while the processor stays

in Real Mode, it can access only the memory

range FFFF_0000h to FFFF_FFFFh.

If BIOS were to modify CS while still in Real Mode, the processor would only be able to address 0_0000h to F_FFFFh.

PAM0 helps out by mapping this range to high memory (another decoder)

So therefore if your BIOS is large enough that it is mapped below FFFF_0000H and you want to access that part of it, you best get yourself into Protected Mode ASAP.

And this is typically what they do

Слайд 24

Analyzing any x86 BIOS Binary

With UEFI we can

usually skip straight to analyzing code we care about.

But

what if you want to analyze a legacy BIOS, or some other non-UEFI x86 BIOS like CoreBoot?

In that case you may need to do as the computer does, and really read starting from the first instruction

The subsequent slides provide the generic process to do that

Слайд 25

A dream deferred

We’re going to hold off on

the rest of the entry vector analysis for now,

and go back to it later if we have time.

We never have time ;)

I left the slides in here for if you want to try to go through an equivalent process

Note: I know the slides are a little hard to follow and occasionally make jumps in intuition. I’ve been wanting to clean these up from John’s version, but haven’t had time

Слайд 26

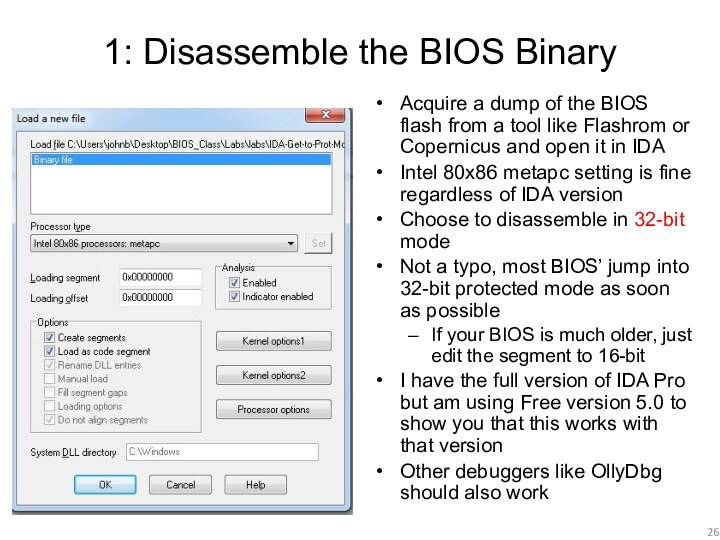

1: Disassemble the BIOS Binary

Acquire a dump of

the BIOS flash from a tool like Flashrom or

Copernicus and open it in IDA

Intel 80x86 metapc setting is fine regardless of IDA version

Choose to disassemble in 32-bit mode

Not a typo, most BIOS’ jump into 32-bit protected mode as soon as possible

If your BIOS is much older, just edit the segment to 16-bit

I have the full version of IDA Pro but am using Free version 5.0 to show you that this works with that version

Other debuggers like OllyDbg should also work

Слайд 27

FIXME

Update procedure for new IDA demo 6.6

Слайд 28

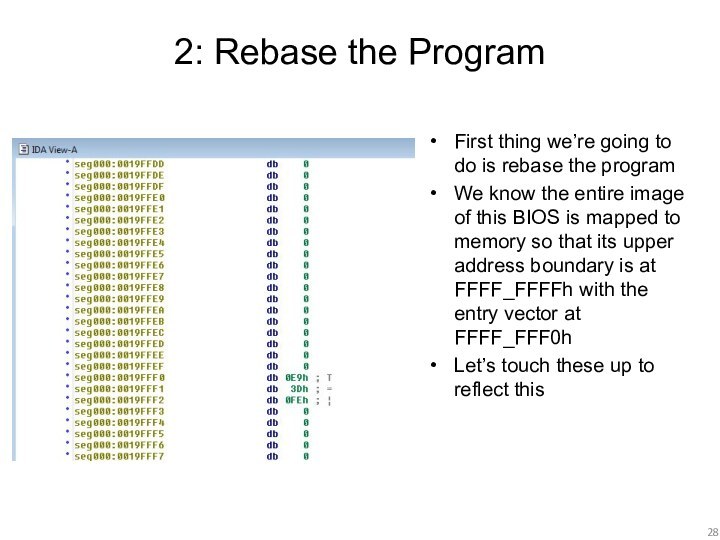

2: Rebase the Program

First thing we’re going to

do is rebase the program

We know the entire

image of this BIOS is mapped to memory so that its upper address boundary is at FFFF_FFFFh with the entry vector at FFFF_FFF0h

Let’s touch these up to reflect this

Слайд 29

2.1: Rebase the Program

In this lab our file

contains only the BIOS portion of the flash.

The value

to enter is:

4 GB – (Size of BIOS Binary)

For this lab it is 0xFFE60000

(for BIOS Length 1A0000h)

Example: If you had a 2 MB BIOS binary you would rebase the program to FFE0_0000h

The idea is for the entry vector at FFFF_FFF0h in memory to be displayed in IDA at linear address FFFF_FFF0h

If you encounter a size-related error, open the binary file with a hex editor (like HxD) and delete the last byte. Then re-open the binary in IDA and rebase it. Still treat it like it were its original size.

!

Слайд 30

2.2: Rebase the Program

You know you have done

it right when you see executable instructions at FFFF_FFF0h,

such as:

E9 3D FE

E9 is a relative JMP instruction (JMP FE3Dh)

Note: The JMP instruction may be preceded by a WBINVD instruction or a couple NOP instructions

In this case, these instructions will be at FFFF_FFF0h instead of the JMP

There always will be a JMP here following those

Слайд 31

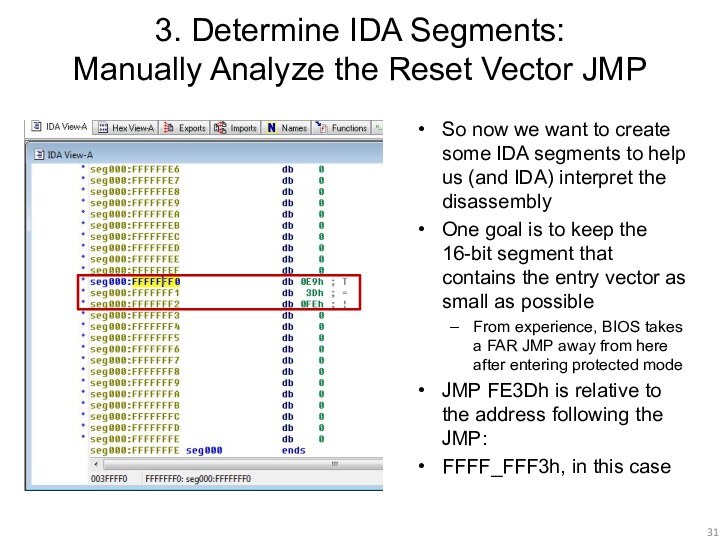

3. Determine IDA Segments:

Manually Analyze the Reset

Vector JMP

So now we want to create some IDA

segments to help us (and IDA) interpret the disassembly

One goal is to keep the 16-bit segment that contains the entry vector as small as possible

From experience, BIOS takes a FAR JMP away from here after entering protected mode

JMP FE3Dh is relative to the address following the JMP:

FFFF_FFF3h, in this case

Слайд 32

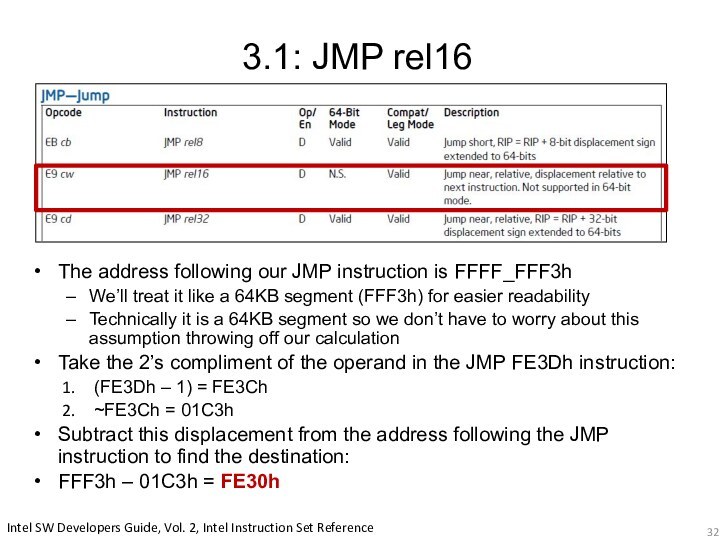

3.1: JMP rel16

The address following our JMP instruction

is FFFF_FFF3h

We’ll treat it like a 64KB segment

(FFF3h) for easier readability

Technically it is a 64KB segment so we don’t have to worry about this assumption throwing off our calculation

Take the 2’s compliment of the operand in the JMP FE3Dh instruction:

(FE3Dh – 1) = FE3Ch

~FE3Ch = 01C3h

Subtract this displacement from the address following the JMP instruction to find the destination:

FFF3h – 01C3h = FE30h

Intel SW Developers Guide, Vol. 2, Intel Instruction Set Reference

Слайд 33

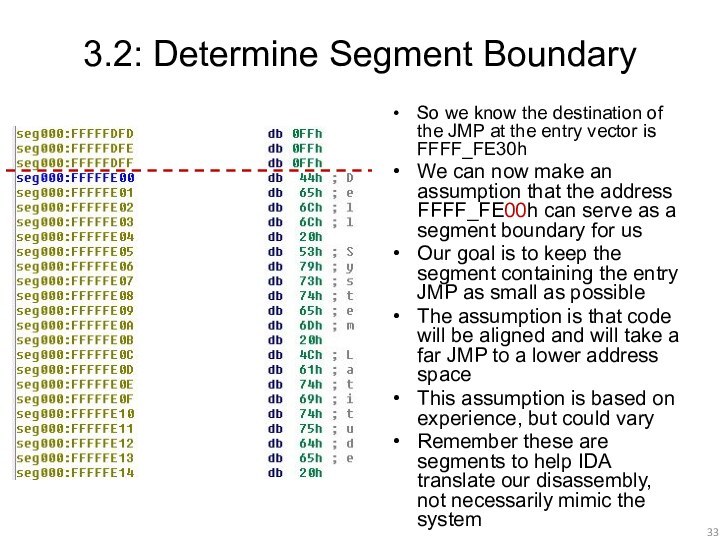

3.2: Determine Segment Boundary

So we know the destination

of the JMP at the entry vector is FFFF_FE30h

We

can now make an assumption that the address FFFF_FE00h can serve as a segment boundary for us

Our goal is to keep the segment containing the entry JMP as small as possible

The assumption is that code will be aligned and will take a far JMP to a lower address space

This assumption is based on experience, but could vary

Remember these are segments to help IDA translate our disassembly, not necessarily mimic the system

Слайд 34

4: Create Initial 16-bit Segment

Edit –> Segments –>

Create Segment

Pick any segment name you want

Class can be

any text name

16-bit segment

Start Address = 0xFFFFFE00

End Address = 0xFFFFFFFE

Remember: IDA Does not like the address FFFFFFFF (-1) !!

Actually, according to IDA documentation, the 32-bit version of IDA doesn’t “like” any address at or above FF00_0000h ☹

Base = 0x0FFFF000

CS.BASE = FFFF_0000h on boot

VirtualAddress = LinearAddress - (Base << 4)

FFF0 FFFF:FFF0 – (Base << 4)

Слайд 35

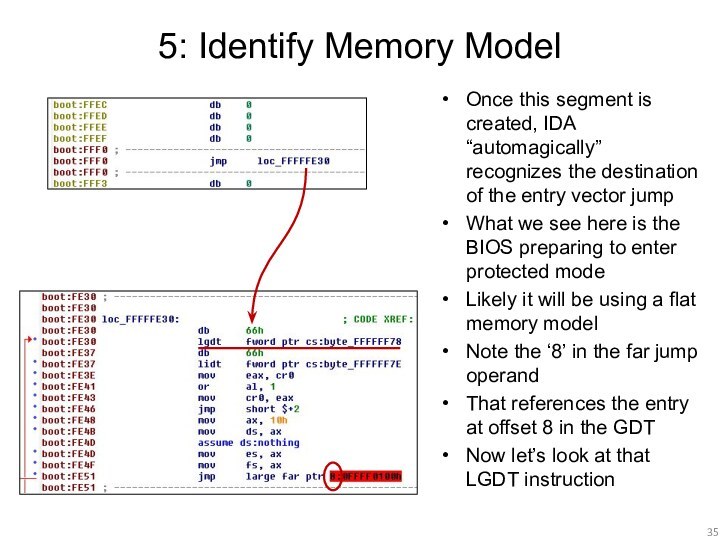

5: Identify Memory Model

Once this segment is created,

IDA “automagically” recognizes the destination of the entry vector

jump

What we see here is the BIOS preparing to enter protected mode

Likely it will be using a flat memory model

Note the ‘8’ in the far jump operand

That references the entry at offset 8 in the GDT

Now let’s look at that LGDT instruction

Слайд 36

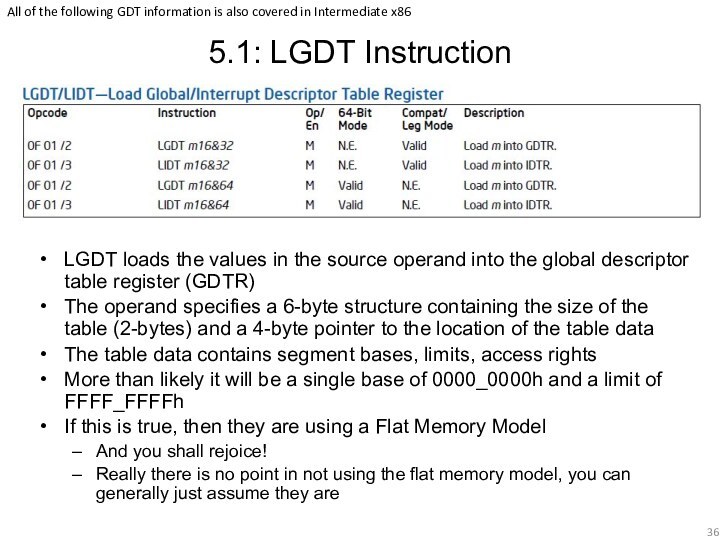

5.1: LGDT Instruction

LGDT loads the values in the

source operand into the global descriptor table register (GDTR)

The

operand specifies a 6-byte structure containing the size of the table (2-bytes) and a 4-byte pointer to the location of the table data

The table data contains segment bases, limits, access rights

More than likely it will be a single base of 0000_0000h and a limit of FFFF_FFFFh

If this is true, then they are using a Flat Memory Model

And you shall rejoice!

Really there is no point in not using the flat memory model, you can generally just assume they are

All of the following GDT information is also covered in Intermediate x86

Слайд 37

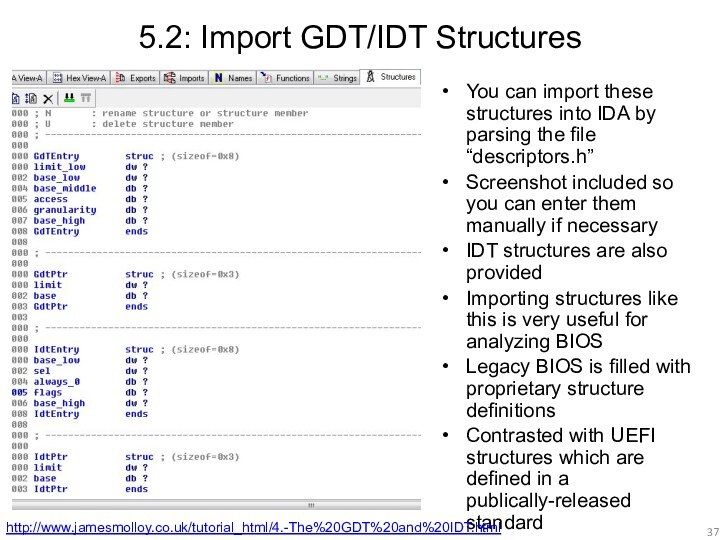

5.2: Import GDT/IDT Structures

You can import these structures

into IDA by parsing the file “descriptors.h”

Screenshot included

so you can enter them manually if necessary

IDT structures are also provided

Importing structures like this is very useful for analyzing BIOS

Legacy BIOS is filled with proprietary structure definitions

Contrasted with UEFI structures which are defined in a publically-released standard

http://www.jamesmolloy.co.uk/tutorial_html/4.-The%20GDT%20and%20IDT.html

Слайд 38

5.3: Define GdtPtr

Go to the address referenced by

the operand to the LGDT instruction

IDA will have already

tried to interpret this and failed, undefine that

Now define it as structure of type GdtPtr

As per the structure definition, the first member is the size of the GDT table and the second is a pointer to the location of the GDT entries

That pointer won’t translate properly for us, but we can tell where the entries are defined just by looking at the value

Слайд 39

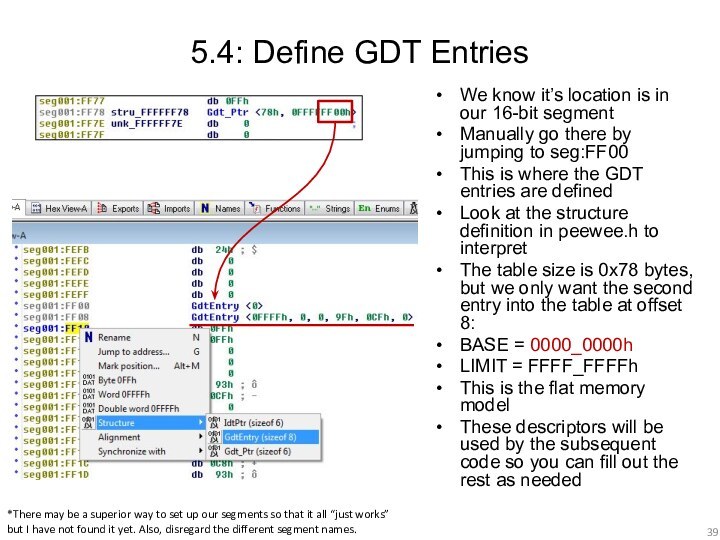

5.4: Define GDT Entries

We know it’s location is

in our 16-bit segment

Manually go there by jumping

to seg:FF00

This is where the GDT entries are defined

Look at the structure definition in peewee.h to interpret

The table size is 0x78 bytes, but we only want the second entry into the table at offset 8:

BASE = 0000_0000h

LIMIT = FFFF_FFFFh

This is the flat memory model

These descriptors will be used by the subsequent code so you can fill out the rest as needed

*There may be a superior way to set up our segments so that it all “just works”

but I have not found it yet. Also, disregard the different segment names.

Слайд 40

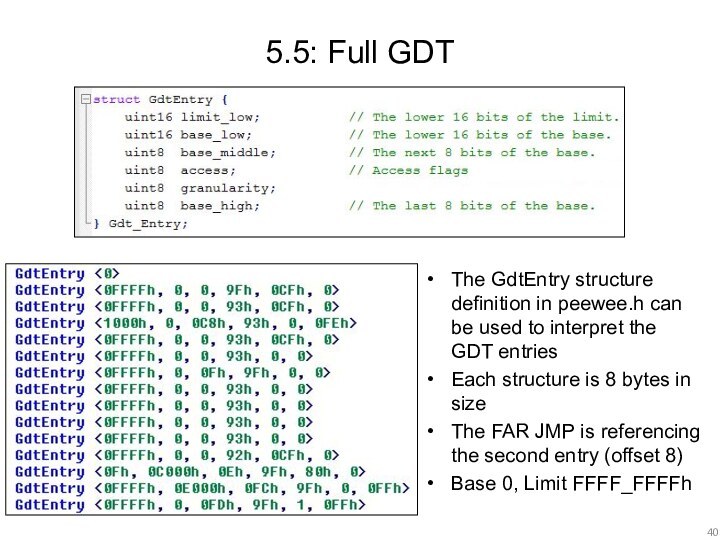

5.5: Full GDT

The GdtEntry structure definition in peewee.h

can be used to interpret the GDT entries

Each structure

is 8 bytes in size

The FAR JMP is referencing the second entry (offset 8)

Base 0, Limit FFFF_FFFFh

Слайд 41

5.5: Full GDT

Here is the entire GDT for

reference. You don’t need an expensive debugger to analyze

BIOS (but it does save a lot of time)

Слайд 42

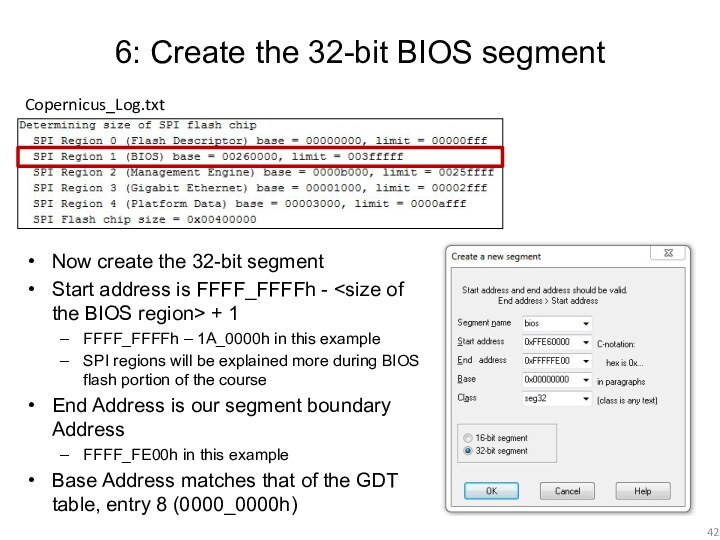

6: Create the 32-bit BIOS segment

Now create the

32-bit segment

Start address is FFFF_FFFFh -

BIOS region> + 1

FFFF_FFFFh – 1A_0000h in this example

SPI regions will be explained more during BIOS flash portion of the course

End Address is our segment boundary Address

FFFF_FE00h in this example

Base Address matches that of the GDT table, entry 8 (0000_0000h)

Copernicus_Log.txt

Слайд 43

7: Touch up the Far Jump

So we know

that this is loading the descriptor entry at offset

8 in the GDT

We can visually inspect the operand of this JMP to see that it’s going to FFFF_0100h

We can manually fix this operand

Right click the operand and select ‘Manual’

Change it to:

bios:FFFF0100h

Uncheck ‘Check Operand’

A little ugly

Слайд 44

Welcome to BIOS Analysis

Converting the binary at FFFF_0100h

to code provides you the entry point to the

real BIOS initialization

Up until this point everything we covered is pretty standard across many BIOSes

This applies to UEFI BIOS too

Even really old BIOS will basically follow the path we took, perhaps staying in real mode longer though

From here on though, if legacy, it’s completely proprietary to the OEM (data structures, etc.)

By contrast, UEFI is standardized from head to toe

Слайд 45

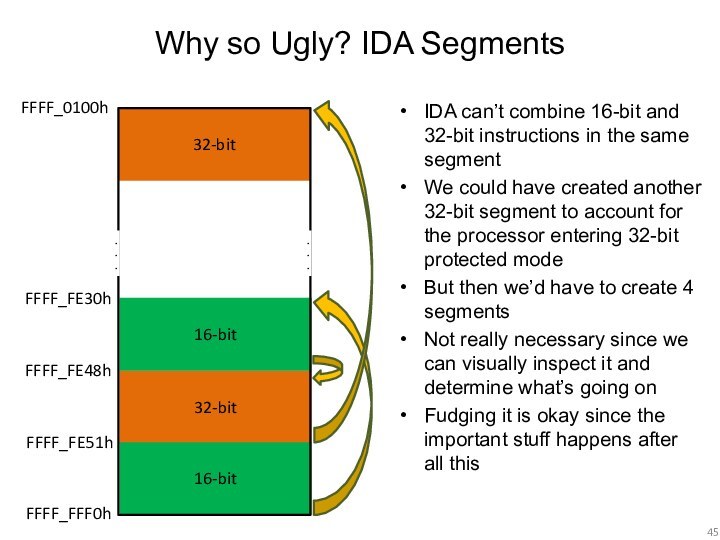

Why so Ugly? IDA Segments

IDA can’t combine 16-bit

and 32-bit instructions in the same segment

We could have

created another 32-bit segment to account for the processor entering 32-bit protected mode

But then we’d have to create 4 segments

Not really necessary since we can visually inspect it and determine what’s going on

Fudging it is okay since the important stuff happens after all this

32-bit

16-bit

16-bit

FFFF_FFF0h

FFFF_FE30h

FFFF_FE48h

FFFF_FE51h

32-bit

.

.

.

.

.

.

FFFF_0100h

Слайд 46

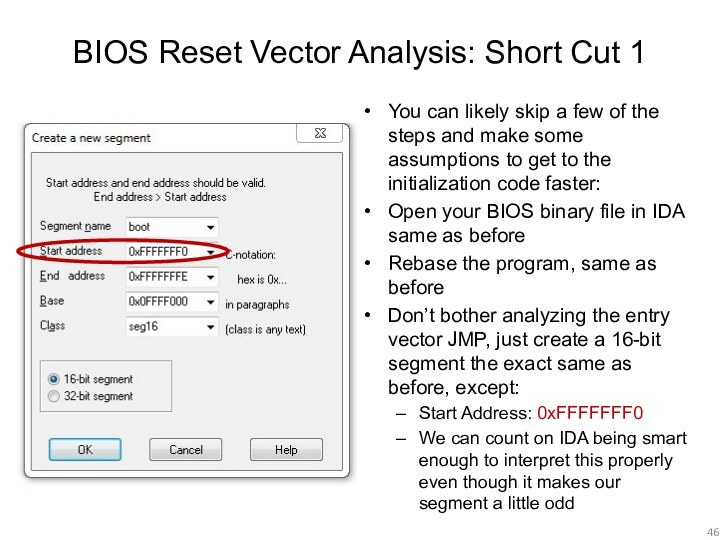

BIOS Reset Vector Analysis: Short Cut 1

You can

likely skip a few of the steps and make

some assumptions to get to the initialization code faster:

Open your BIOS binary file in IDA same as before

Rebase the program, same as before

Don’t bother analyzing the entry vector JMP, just create a 16-bit segment the exact same as before, except:

Start Address: 0xFFFFFFF0

We can count on IDA being smart enough to interpret this properly even though it makes our segment a little odd

Слайд 47

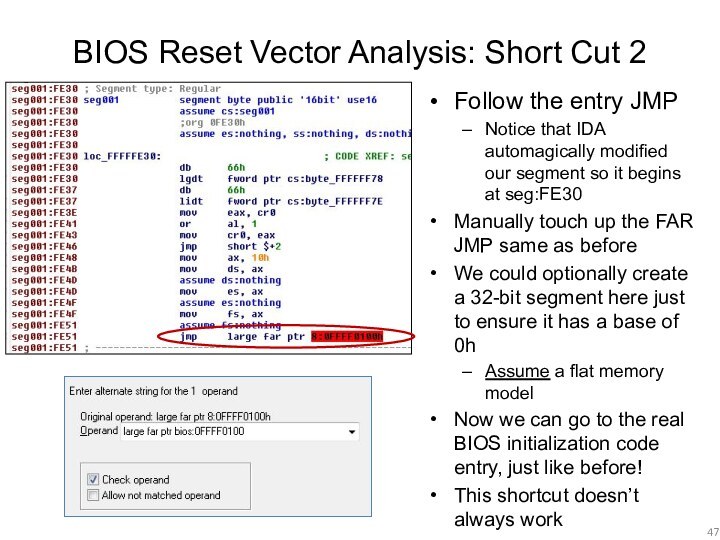

BIOS Reset Vector Analysis: Short Cut 2

Follow the

entry JMP

Notice that IDA automagically modified our segment so

it begins at seg:FE30

Manually touch up the FAR JMP same as before

We could optionally create a 32-bit segment here just to ensure it has a base of 0h

Assume a flat memory model

Now we can go to the real BIOS initialization code entry, just like before!

This shortcut doesn’t always work