- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Global financial crisis 2007–2009

Содержание

- 2. Commodities boomRapid increases in a number of

- 3. Systemic crisisAnother analysis, different from the mainstream

- 4. Systemic crisisBogle cites particular issues, including:that "Manager's

- 5. Role of economic forecastingThe financial crisis was

- 6. Impact on financial marketsThe U.S. stock market

- 7. Financial institutions2007 bank run on Northern Rock, a UK bank

- 8. Financial institutionsThe first notable event signaling a

- 9. Credit markets and the shadow banking systemDuring

- 10. The Fed Responds to the Crisis

- 11. Wealth effectsThere is a direct relationship between

- 12. European contagionThe crisis rapidly developed and spread

- 13. Effects on the global economyUBS : the

- 14. Effects on the global economyThe WB in

- 15. Effects on the global economyA number of

- 16. Скачать презентацию

- 17. Похожие презентации

Commodities boomRapid increases in a number of commodity prices followed the collapse in the housing bubble. The price of oil nearly tripled from $50 to $147 from early 2007 to 2008, before plunging as the financial

Слайд 3

Systemic crisis

Another analysis, different from the mainstream explanation,

is that the financial crisis is merely a symptom

of another, deeper crisis, which is a systemic crisis of capitalism itself.Ravi Batra's theory is that growing inequality of financial capitalism produces speculative bubbles that burst and result in depression and major political changes. He has also suggested that a "demand gap" related to differing wage and productivity growth explains deficit and debt dynamics important to stock market developments.

John Bellamy Foster, a political economy analyst and editor of the Monthly Review, believes that the decrease in GDP growth rates since the early 1970s is due to increasing market saturation.

John C. Bogle wrote during 2005 that a series of unresolved challenges face capitalism that have contributed to past financial crises and have not been sufficiently addressed:

Corporate America went astray largely because the power of managers went virtually unchecked by our gatekeepers for far too long... They failed to 'keep an eye on these geniuses' to whom they had entrusted the responsibility of the management of America's great corporations.

Слайд 4

Systemic crisis

Bogle cites particular issues, including:

that "Manager's capitalism"

has replaced "owner's capitalism", meaning management runs the firm

for its benefit rather than for the shareholders, a variation on the principal–agent problem;the burgeoning executive compensation;

the management of earnings, mainly a focus on share price rather than the creation of genuine value; and

the failure of gatekeepers, including auditors, boards of directors, Wall Street analysts, and career politicians.

Former executive at the Swiss-based UBS Bank Roeder suggested that "recent technological advances, such as computer-driven trading programs, together with the increasingly interconnected nature of markets, has magnified the momentum effect. This has made the financial sector inherently unstable."

Robert Reich has attributed the current economic downturn to the stagnation of wages in the United States, particularly those of the hourly workers who comprise 80% of the workforce. His claim is that this stagnation forced the population to borrow in order to meet the cost of living.

Слайд 5

Role of economic forecasting

The financial crisis was not

widely predicted by mainstream economists, who instead spoke of

the Great Moderation.A number of heterodox economists predicted the crisis, with varying arguments.

Examples of other experts who gave indications of a financial crisis have also been given. Not surprisingly, the Austrian economic school regarded the crisis as a vindication and classic example of a predictable credit-fueled bubble that could not forestall the disregarded but inevitable effect of an artificial, manufactured ilaxity (расхлябанность) in monetary supply, a perspective that even former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan in Congressional testimony confessed himself forced to return to.

A cover story in BusinessWeek magazine claims that economists mostly failed to predict the worst international economic crisis since the Great Depression of 1930s.

The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania's online business journal examines why economists failed to predict a major global financial crisis. Popular articles published in the mass media have led the general public to believe that the majority of economists have failed in their obligation to predict the financial crisis.

Аn article in the New York Times informs that economist Nouriel Roubini warned of such crisis as early as September 2006, and the article goes on to state that the profession of economics is bad at predicting recessions. According to The Guardian, Roubini was ridiculed for predicting a collapse of the housing market and worldwide recession, while The New York Times labelled him "Dr. Doom (доктор «Смерть»)

Слайд 6

Impact on financial markets

The U.S. stock market peaked

in October 2007, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average

index exceeded 14,000 points.It then entered a pronounced decline, which accelerated markedly in October 2008.

By March 2009, the Dow Jones average had reached a trough of around 6,600.

Four years later, it hit an all-time high. It is probable, but debated, that the Federal Reserve's aggressive policy of quantitative easing spurred the partial recovery in the stock market.

Слайд 8

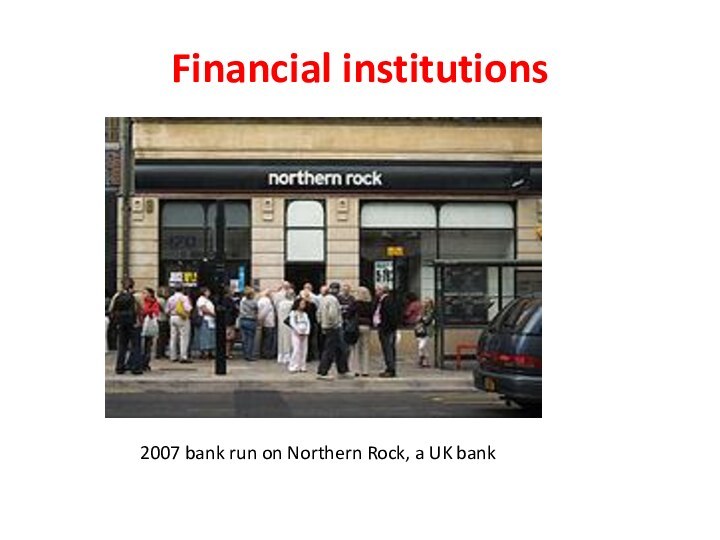

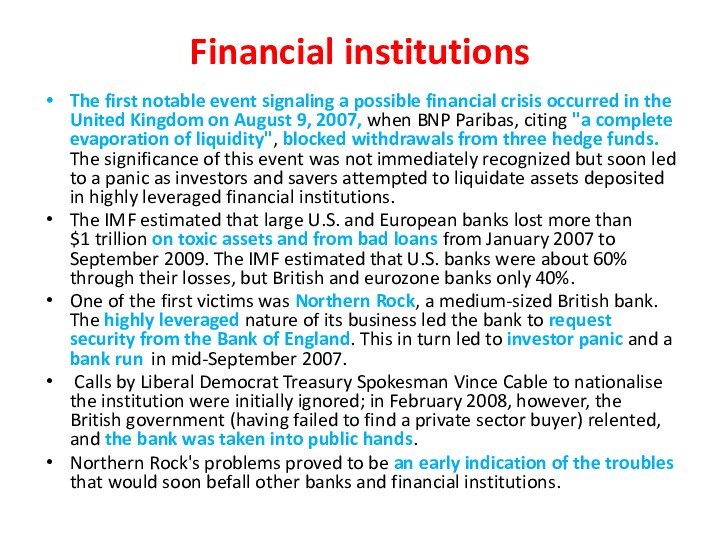

Financial institutions

The first notable event signaling a possible

financial crisis occurred in the United Kingdom on August

9, 2007, when BNP Paribas, citing "a complete evaporation of liquidity", blocked withdrawals from three hedge funds. The significance of this event was not immediately recognized but soon led to a panic as investors and savers attempted to liquidate assets deposited in highly leveraged financial institutions.The IMF estimated that large U.S. and European banks lost more than $1 trillion on toxic assets and from bad loans from January 2007 to September 2009. The IMF estimated that U.S. banks were about 60% through their losses, but British and eurozone banks only 40%.

One of the first victims was Northern Rock, a medium-sized British bank. The highly leveraged nature of its business led the bank to request security from the Bank of England. This in turn led to investor panic and a bank run in mid-September 2007.

Calls by Liberal Democrat Treasury Spokesman Vince Cable to nationalise the institution were initially ignored; in February 2008, however, the British government (having failed to find a private sector buyer) relented, and the bank was taken into public hands.

Northern Rock's problems proved to be an early indication of the troubles that would soon befall other banks and financial institutions.

Слайд 9

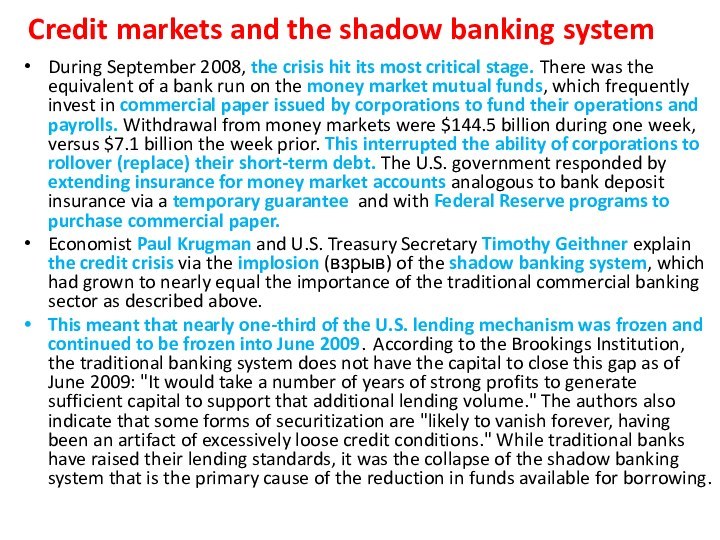

Credit markets and the shadow banking system

During September

2008, the crisis hit its most critical stage. There

was the equivalent of a bank run on the money market mutual funds, which frequently invest in commercial paper issued by corporations to fund their operations and payrolls. Withdrawal from money markets were $144.5 billion during one week, versus $7.1 billion the week prior. This interrupted the ability of corporations to rollover (replace) their short-term debt. The U.S. government responded by extending insurance for money market accounts analogous to bank deposit insurance via a temporary guarantee and with Federal Reserve programs to purchase commercial paper.Economist Paul Krugman and U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner explain the credit crisis via the implosion (взрыв) of the shadow banking system, which had grown to nearly equal the importance of the traditional commercial banking sector as described above.

This meant that nearly one-third of the U.S. lending mechanism was frozen and continued to be frozen into June 2009. According to the Brookings Institution, the traditional banking system does not have the capital to close this gap as of June 2009: "It would take a number of years of strong profits to generate sufficient capital to support that additional lending volume." The authors also indicate that some forms of securitization are "likely to vanish forever, having been an artifact of excessively loose credit conditions." While traditional banks have raised their lending standards, it was the collapse of the shadow banking system that is the primary cause of the reduction in funds available for borrowing.

Слайд 11

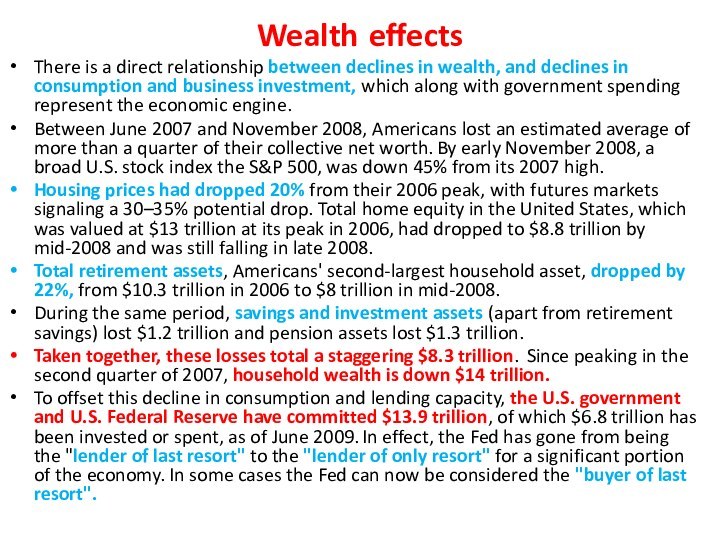

Wealth effects

There is a direct relationship between declines

in wealth, and declines in consumption and business investment,

which along with government spending represent the economic engine.Between June 2007 and November 2008, Americans lost an estimated average of more than a quarter of their collective net worth. By early November 2008, a broad U.S. stock index the S&P 500, was down 45% from its 2007 high.

Housing prices had dropped 20% from their 2006 peak, with futures markets signaling a 30–35% potential drop. Total home equity in the United States, which was valued at $13 trillion at its peak in 2006, had dropped to $8.8 trillion by mid-2008 and was still falling in late 2008.

Total retirement assets, Americans' second-largest household asset, dropped by 22%, from $10.3 trillion in 2006 to $8 trillion in mid-2008.

During the same period, savings and investment assets (apart from retirement savings) lost $1.2 trillion and pension assets lost $1.3 trillion.

Taken together, these losses total a staggering $8.3 trillion. Since peaking in the second quarter of 2007, household wealth is down $14 trillion.

To offset this decline in consumption and lending capacity, the U.S. government and U.S. Federal Reserve have committed $13.9 trillion, of which $6.8 trillion has been invested or spent, as of June 2009. In effect, the Fed has gone from being the "lender of last resort" to the "lender of only resort" for a significant portion of the economy. In some cases the Fed can now be considered the "buyer of last resort".

Слайд 12

European contagion

The crisis rapidly developed and spread into

a global economic shock, resulting in 1. a number

of European bank failures, 2. declines in various stock indexes, and 3. large reductions in the market value of equities and commodities.Both MBS and CDO were purchased by corporate and institutional investors globally ( GLOBALIZATION!). Derivatives such as credit default swaps also increased the linkage between large financial institutions. Moreover, the de-leveraging of financial institutions, as assets were sold to pay back obligations that could not be refinanced in frozen credit markets, further accelerated the solvency crisis and caused a decrease in international trade.

World political leaders, national ministers of finance and central bank directors coordinated their efforts to reduce fears, but the crisis continued.

At the end of October 2008 a currency crisis developed, with investors transferring vast capital resources into stronger currencies such as the yen, the dollar and the Swiss franc, leading many emergent economies to seek aid from the International Monetary Fund.

Слайд 13

Effects on the global economy

UBS : the forthcoming

recession would be the worst since the early 1980s

recession with negative 2009 growth for the U.S., Eurozone, UK; very limited recovery in 2010; but not as bad as the Great Depression.The Brookings Institution reported in June 2009 that U.S. consumption accounted for more than a third of the growth in global consumption between 2000 and 2007. "The US economy has been spending too much and borrowing too much for years and the rest of the world depended on the U.S. consumer as a source of global demand." With a recession in the U.S. and the increased savings rate of U.S. consumers, declines in growth elsewhere have been dramatic. For the first quarter of 2009, the annualized rate of decline in GDP was 14.4% in Germany, 15.2% in Japan, 7.4% in the UK, 18% in Latvia, 9.8% in the Euro area and 21.5% for Mexico.

Some developing countries that had seen strong economic growth saw significant slowdowns. For example, growth forecasts in Cambodia show a fall from more than 10% in 2007 to close to zero in 2009, and Kenya may achieve only 3–4% growth in 2009, down from 7% in 2007. According to the research by the Overseas Development Institute, reductions in growth can be attributed to falls in trade, commodity prices, investment and remittance sent from migrant workers (which reached a record $251 billion in 2007, but have fallen in many countries since). This has stark implications and has led to a dramatic rise in the number of households living below the poverty line, be it 300,000 in Bangladesh or 230,000 in Ghana. Especially states with a fragile political system have to fear that investors from Western states withdraw their money because of the crisis.

Слайд 14

Effects on the global economy

The WB in February

2009: the Arab World was far less severely affected

by the credit crunch. With generally good balance of payments positions coming into the crisis or with alternative sources of financing for their large current account deficits, such as remittances, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) or foreign aid, Arab countries were able to avoid going to the market in the latter part of 2008. This group is in the best position to absorb the economic shocks. They entered the crisis in exceptionally strong positions. This gives them a significant cushion against the global downturn. The greatest impact of the global economic crisis will come in the form of lower oil prices, which remains the single most important determinant of economic performance. Steadily declining oil prices would force them to draw down reserves and cut down on investments. Significantly lower oil prices could cause a reversal of economic performance as has been the case in past oil shocks. Initial impact will be seen on public finances and employment for foreign workers.

Слайд 15

Effects on the global economy

A number of commentators

have suggested that if the liquidity crisis continues, there

could be an extended recession or worse. The continuing development of the crisis has prompted in some quarters fears of a global economic collapse although there are now many cautiously optimistic forecasters in addition to some prominent sources who remain negative.The financial crisis is likely to yield the biggest banking shakeout since the savings-and-loan meltdown. Investment bank UBS stated on October 6 that 2008 would see a clear global recession, with recovery unlikely for at least two years.

Three days later UBS economists announced that the "beginning of the end" of the crisis had begun, with the world starting to make the necessary actions to fix the crisis: capital injection by governments; injection made systemically; interest rate cuts to help borrowers.

The United Kingdom had started systemic injection, and the world's central banks were now cutting interest rates.

UBS emphasized the United States needed to implement systemic injection. UBS further emphasized that this fixes only the financial crisis, but that in economic terms "the worst is still to come".

The economic crisis in Iceland involved all three of the country's major banks. Relative to the size of its economy, Iceland’s banking collapse is the largest suffered by any country in economic history.