- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему The faces of Britain

Содержание

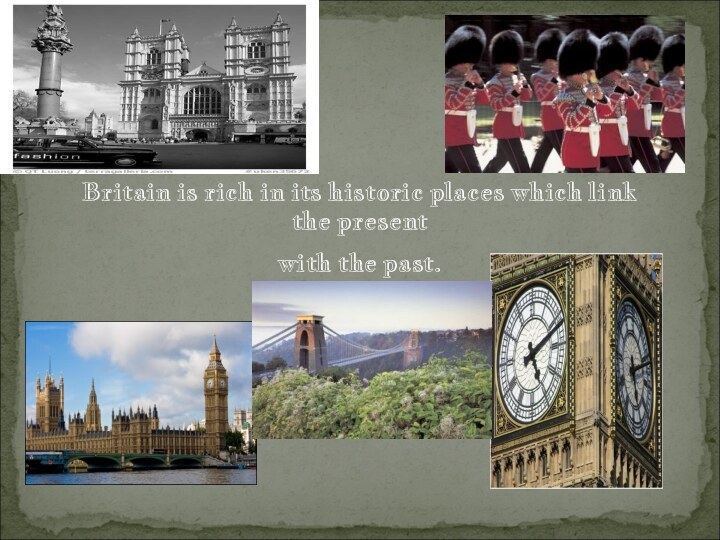

- 2. Britain is rich in its historic places which link the present with the past.

- 3. Every nation and every country has

- 4. Hadrian’s Wall Running across northern England, from

- 5. Hadrian wall is a sign- the

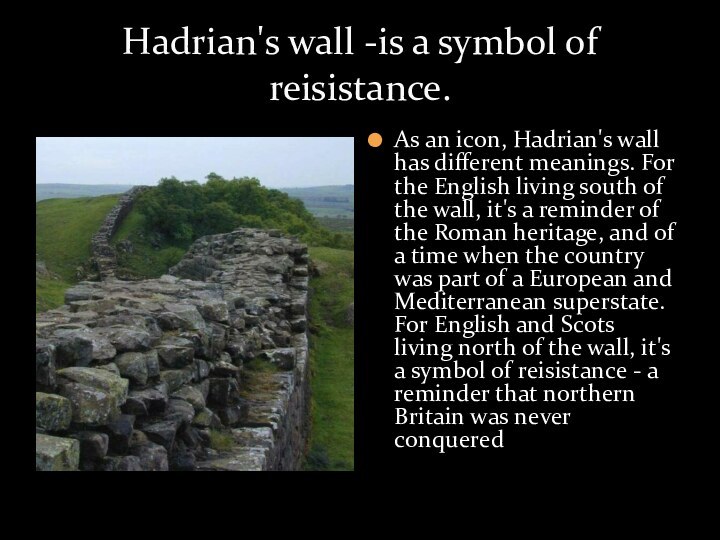

- 6. Hadrian's wall -is a symbol of reisistance.As

- 7. The Iron Bridge A modestly sized bridge

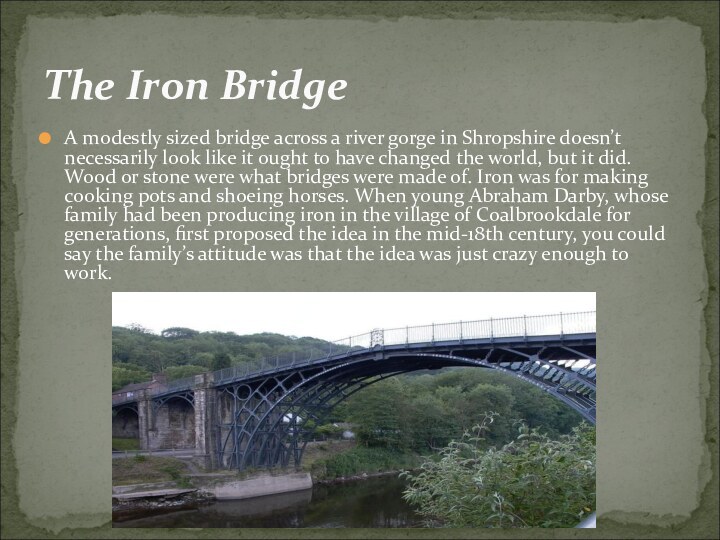

- 8. The Iron Bridge represented a major turning-point

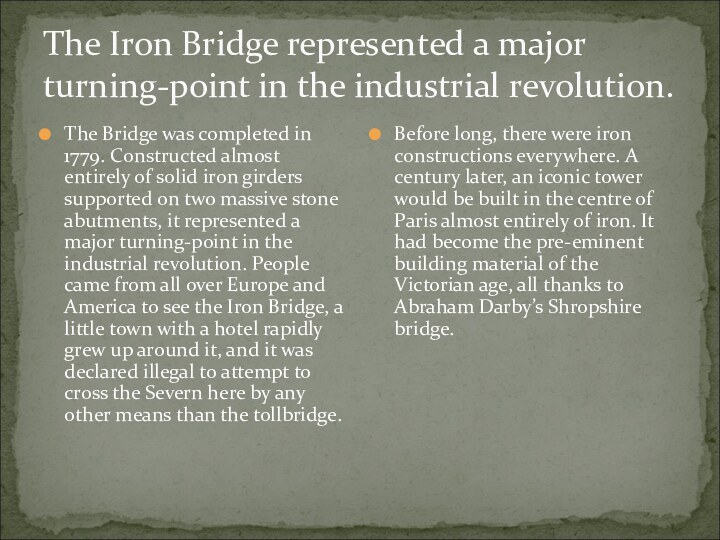

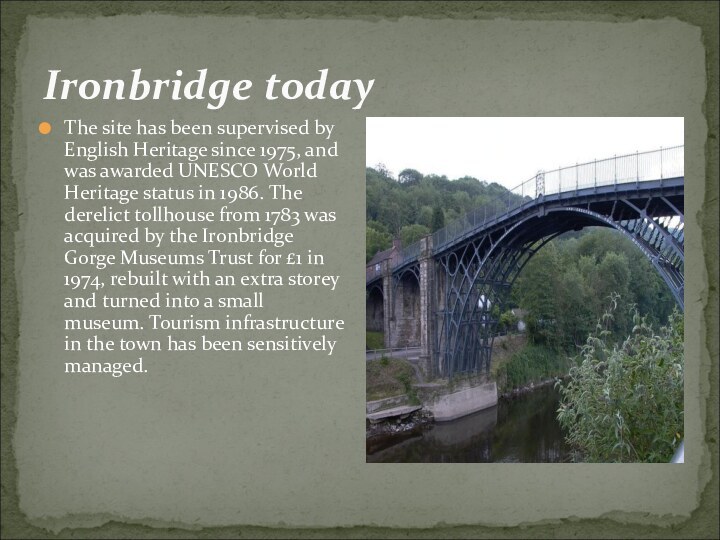

- 9. Ironbridge todayThe site has been supervised by

- 10. Around the end of the Bridge are

- 11. BOWLER

- 12. BOWLER HATNo other style of hat, before

- 13. How Popular are they Now? In

- 14. THE V-signWhere did the V-sign come from?

- 15. THE RUDE VERSION In Britain, the V-sign

- 16. V FOR VICTORY The V-sign also stands

- 17. The Churchillian gesture Winston Churchill took up

- 18. Around the world The V

- 19. THE ARCHERS' V-SIGN: AN URBAN LEGEND The

- 20. THE ARCHERS' V-SIGN: AN URBAN LEGENDThe greatest

- 21. THE ARCHERS' V-SIGN: AN URBAN LEGENDA story

- 22. Land Rover Used around the world, but

- 23. Land Rover’s history The Rover Cycle Company

- 24. CHEDDAR CHEESEFeeling peckish? Then let us offer

- 25. CHEDDAR CHEESEWe know of a local cheese

- 26. We should note that it is possible

- 27. Bibliography:The book “1000 English topics” V.

- 28. Скачать презентацию

- 29. Похожие презентации

Слайд 3 Every nation and every country has its own

customs and traditions. In Britain traditions play a more

important part in people's life than in other countries.One of the most striking features of British life is the self-discipline and courtesy of people of all classes.

The British don't like displaying their emotions even in dangerous and tragic situations, and ordinary people seem to remain good-tempered and cheerful under difficulties.

They don't like any boasting or showing off in manners, dress or speech.

Слайд 4

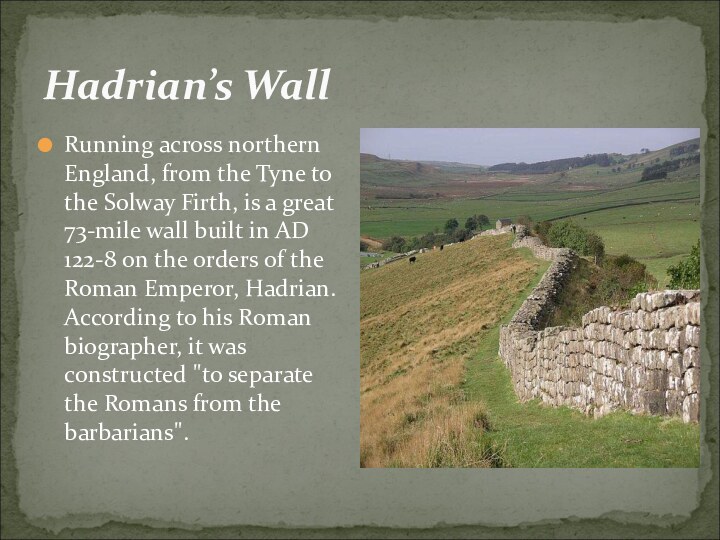

Hadrian’s Wall

Running across northern England, from the

Tyne to the Solway Firth, is a great 73-mile

wall built in AD 122-8 on the orders of the Roman Emperor, Hadrian. According to his Roman biographer, it was constructed "to separate the Romans from the barbarians".Слайд 5 Hadrian wall is a sign- the whole

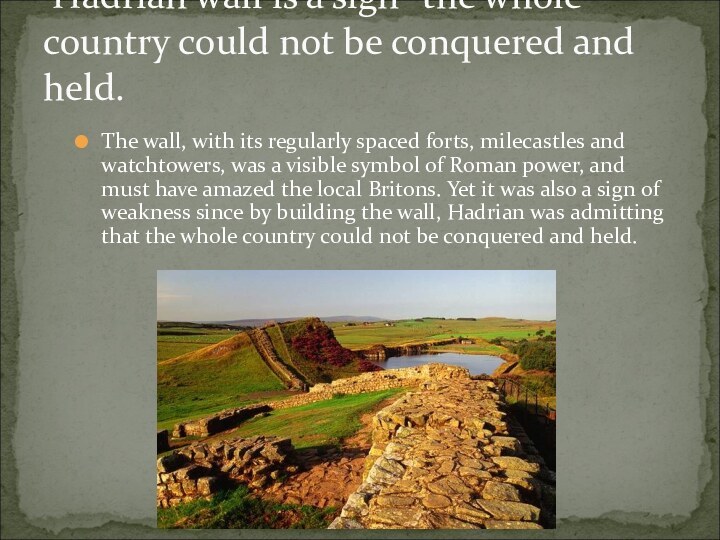

country could not be conquered and held.

The wall, with

its regularly spaced forts, milecastles and watchtowers, was a visible symbol of Roman power, and must have amazed the local Britons. Yet it was also a sign of weakness since by building the wall, Hadrian was admitting that the whole country could not be conquered and held.

Слайд 6

Hadrian's wall -is a symbol of reisistance.

As an

icon, Hadrian's wall has different meanings. For the English

living south of the wall, it's a reminder of the Roman heritage, and of a time when the country was part of a European and Mediterranean superstate. For English and Scots living north of the wall, it's a symbol of reisistance - a reminder that northern Britain was never conquered

Слайд 7

The Iron Bridge

A modestly sized bridge across

a river gorge in Shropshire doesn’t necessarily look like

it ought to have changed the world, but it did. Wood or stone were what bridges were made of. Iron was for making cooking pots and shoeing horses. When young Abraham Darby, whose family had been producing iron in the village of Coalbrookdale for generations, first proposed the idea in the mid-18th century, you could say the family’s attitude was that the idea was just crazy enough to work.Слайд 8 The Iron Bridge represented a major turning-point in

the industrial revolution.

The Bridge was completed in 1779. Constructed

almost entirely of solid iron girders supported on two massive stone abutments, it represented a major turning-point in the industrial revolution. People came from all over Europe and America to see the Iron Bridge, a little town with a hotel rapidly grew up around it, and it was declared illegal to attempt to cross the Severn here by any other means than the tollbridge.Before long, there were iron constructions everywhere. A century later, an iconic tower would be built in the centre of Paris almost entirely of iron. It had become the pre-eminent building material of the Victorian age, all thanks to Abraham Darby’s Shropshire bridge.

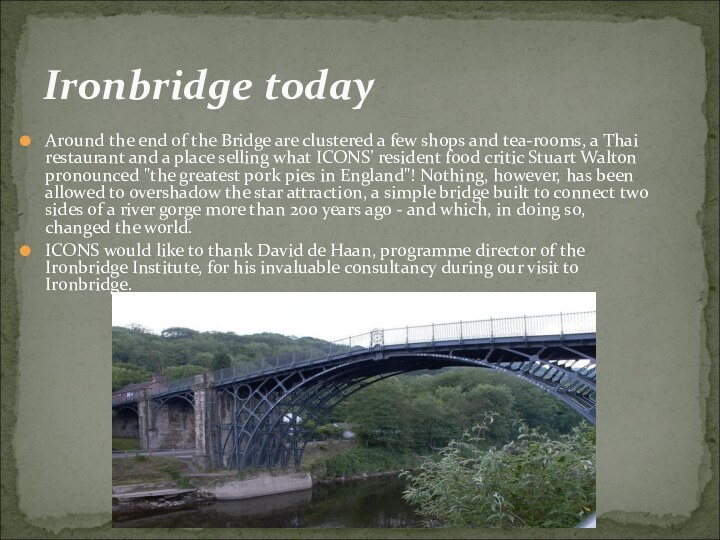

Слайд 9

Ironbridge today

The site has been supervised by English

Heritage since 1975, and was awarded UNESCO World Heritage

status in 1986. The derelict tollhouse from 1783 was acquired by the Ironbridge Gorge Museums Trust for £1 in 1974, rebuilt with an extra storey and turned into a small museum. Tourism infrastructure in the town has been sensitively managed.Слайд 10 Around the end of the Bridge are clustered

a few shops and tea-rooms, a Thai restaurant and

a place selling what ICONS’ resident food critic Stuart Walton pronounced "the greatest pork pies in England"! Nothing, however, has been allowed to overshadow the star attraction, a simple bridge built to connect two sides of a river gorge more than 200 years ago - and which, in doing so, changed the world.ICONS would like to thank David de Haan, programme director of the Ironbridge Institute, for his invaluable consultancy during our visit to Ironbridge.

Ironbridge today

Слайд 11 BOWLER HAT

From the 1850s to Today

THE HISTORY OF THE BOWLER

HAT, INVENTED IN ENGLAND IN THE MID-19TH CENTURY, IS A MICROCOSM OF OUR MODERN SOCIAL HISTORY.

Слайд 12

BOWLER HAT

No other style of hat, before or

since, not even the ubiquitous baseball cap of recent

years, has so effortlessly crossed the economic barriers of English society, blurring class boundaries and helping to forge new identities among working people. Never solely associated with one particular style of dress, it proved one of the most versatile pieces of headgear ever invented. The bowler hat first made its appearance as the hard hat designed by James Lock and Co. of 6 St James’s Street, London, in 1850 for Sir William Coke, to give his gamewardens to wear when patrolling their employer’s estate on horseback.Слайд 13 How Popular are they Now? In modern English society,

do people still make, sell and wear bowler hats?

The answer is, unsurprisingly, not many. The small number of people who do seems to be divided into two main camps: those who wear them in the course of doing a handful of specific jobs and activities, and (generally elderly) men who wear them because they've done so for a long time.

Although high fashion occasionally revisits the bowler, the number of younger people who will wear such a formal hat is tiny – today most people see the bowler as an eccentric choice.

Слайд 14

THE V-sign

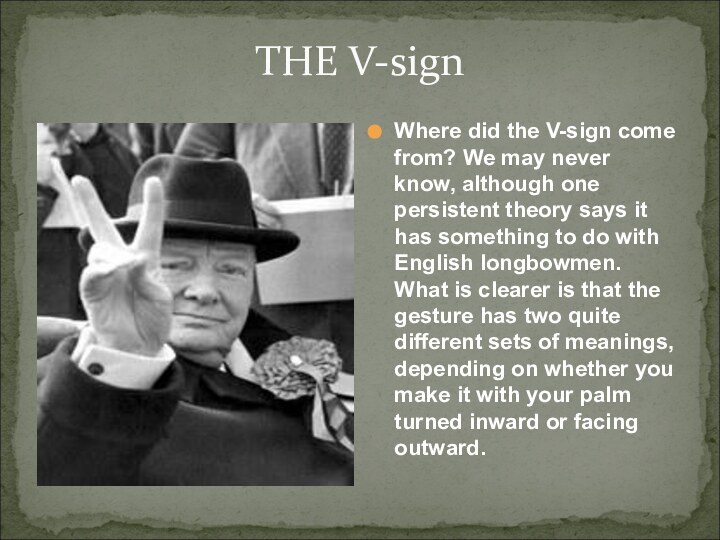

Where did the V-sign come from? We

may never know, although one persistent theory says it

has something to do with English longbowmen. What is clearer is that the gesture has two quite different sets of meanings, depending on whether you make it with your palm turned inward or facing outward.

Слайд 15

THE RUDE VERSION

In Britain, the V-sign -

when done with the palm backwards - is a

rude insult, meaning "Get Stuffed!". Although it is now losing ground to the American single finger, it is still seen from time to time. Recent two-finger saluters include deputy PM John Prescott, Liam Gallagher of Oasis and England striker, Wayne Rooney.The strangest thing about this rude gesture is that nobody knows where it comes from, or even what the two fingers are supposed to represent. The earliest description of an insulting V-sign comes from the French writer, François Rabelais. In his comic epic,Gargantua And Pantagruel (1532), he described a duel of gestures between two characters, Panurge and Thaumast:

Слайд 16

V FOR VICTORY

The V-sign also stands for

"Victory", and unlike the British "Get Stuffed!" sign, this

meaning is understood and used around the world. Popularised by Winston Churchill during world war two, the idea came from a Belgian lawyer called Victor De Lavelaye.On January 4, 1941, Victor De Lavelaye, a Belgian refugee in Britain, made a BBC radio broadcast to his countrymen, in which he suggested a new way of striking at their Nazi occupiers:

I am proposing to you as a rallying emblem the letter V, because V is the first letter of the words 'Victoire' in French, and 'Vrijheid' in Flemish: two things which go together, as Walloons and Flemings are at the moment marching hand in hand, two things which are the consequence one of the other, the Victory which will give us back our freedom, the Victory of our good friends the English. Their word for Victory also begins with V.

Could De Lavelaye have got this idea from his own first name?

Слайд 17

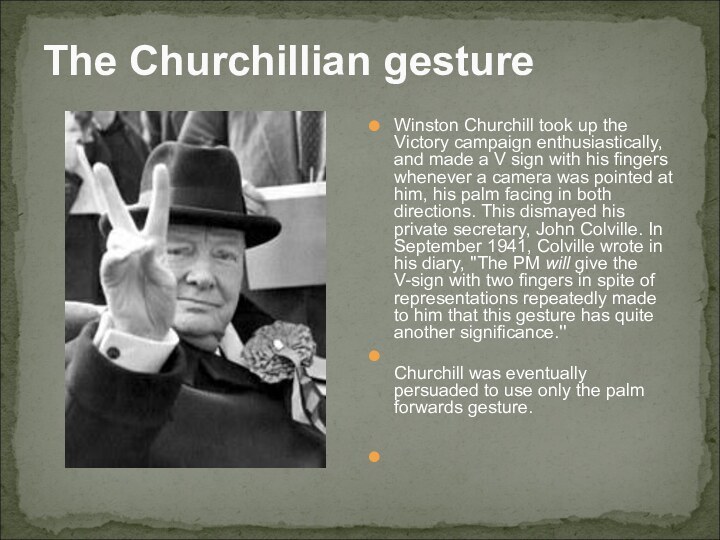

The Churchillian gesture

Winston Churchill took up the

Victory campaign enthusiastically, and made a V sign with

his fingers whenever a camera was pointed at him, his palm facing in both directions. This dismayed his private secretary, John Colville. In September 1941, Colville wrote in his diary, ''The PM will give the V-sign with two fingers in spite of representations repeatedly made to him that this gesture has quite another significance.''Churchill was eventually persuaded to use only the palm forwards gesture.

Слайд 18

Around the world

The V for Victory

gesture is now understood and used worldwide. Following the

first free elections in Iraq,in January 2005, Iraqi women leaving the polling

stations were photographed making the sign triumphantly.

The gesture is also made by Palestinians and Israelis,

by American GIs in Iraq and Afghanistan and by those they fight against.

The Victory gesture can be made with palms facing

in either direction, though the palm forwards

sign is more common - perhaps due to

the influence of Winston Churchill.

Слайд 19

THE ARCHERS' V-SIGN: AN URBAN LEGEND

The rude

V-sign is widely seen as a gesture of English

defiance, supposedly originating in the archers who fought in the 100 Years War against France. Our nominator, Catherine Cooper, wrote, "It was a means of telling your opponent that you were still capable of drawing a bow string back, as you still had two fingers!"

Слайд 20

THE ARCHERS' V-SIGN: AN URBAN LEGEND

The greatest victories

of the 100 Years War, at Crécy (1346), Poitiers

(1356) and Agincourt (1415) were all won by English (and Welsh) longbowmen, raining tens of thousands of arrows down on charging French knights. In each battle, the English army was vastly outnumbered, yet the French threw away their numerical advantage. Due to their deeply ingrained code of chivalry, they believed that the honourable way to fight was using a frontal charge, followed by hand-to-hand combat with English knights, who were their social equals. The French knights viewed the humble archers with contempt, and so they died in their thousands. The archers story is an urban legend - a story, usually false, which appears mysteriously, spreads quickly and is widely believed to be true. In 1968, when the term "urban legend" was invented (by US folklorist Richard Dorsen) such stories spread by word of mouth or through newspapers. Today, thanks to the internet, they can travel much faster and further.

We have several good reasons to distrust the story of the archers. It does not appear in any contemporary account of the Hundred Years War, nor in any academic history of the period.

The story is inherently unlikely. During the Hundred Years War, the only prisoners taken were nobles, protected by the code of chivalry, or those rich enough to have a ransom value. The lives of people outside the chivalric code were seen as worthless. In 1370, for example, Edward the Black Prince, victor of Poitiers, ordered the massacre of 3,000 men, women and children in the French town of Limoges. Yet the Black Prince was seen by both English and French as a ''flower of chivalry".

Like the people of Limoges, English longbowmen were not protected by the code of chivalry, and had no value as prisoners. Why would the French go to the trouble of amputating their fingers when they could just as easily kill them?

In the 1970s, anthropologist and author Desmond Morris made a detailed study of the history of the rude V-sign, and came up with ten possible explanations for its origin. His 1979 book, Gestures, Their Origin And Distribution, has a whole chapter on the sign, yet he does not even mention archers. This suggests that the story was invented after 1979.

Слайд 21

THE ARCHERS' V-SIGN: AN URBAN LEGEND

A story may

be a fiction but, like the legend of Robin

Hood, it can still capture the public imagination. It was in the 1990s that the story of the defiant archers spread. This was a time when many English people felt threatened by the European Community, and hostility to the French in particular was encouraged by the right-wing press.In November 1990, The Sun newspaper ran a famous front page

featuring a picture of a two-fingered salute with the headline,

"UP YOURS DELORS!" This was aimed at Jacques Delors,

the Frenchman who was then head of the European Commission.

The paper was full of hatred directed at the French, described

as people "who INSULT us, BURN our lambs, FLOOD our

country with dodgy food and PLOT to abolish the dear old pound."

Readers were urged to "tell the feelthy French to FROG OFF" by gathering throughout Britain the following day, facing France and at 12 noon shouting "Up Yours Delors!". Two pages carried a town-by-town guide telling readers in which direction to face so that they could aim their anger towards France. People living on the south coast were told to "face the sea and turn steadily to the left until they SMELL the garlic."

Слайд 22

Land Rover

Used around the world, but distinctly

English, the Land Rover is justifiably regarded as one

of England’s most loved and respected pieces of motoring heritage.

Слайд 23

Land Rover’s history

The Rover Cycle Company was

started in 1894 and by 1902 had progressed from

pedal bikes to motor cycles. By 1906 the company was making cars and became known as The Rover Company Limited. During the depression of the 1930s the company struggled, but the arrival of Spencer Wilkes and later his brother Maurice, sparked something of a revival. Between them the dynamic duo built up a reputation for producing high quality cars with superb engineering right up until the outbreak of the Second World War.THE JOURNEY BEGINS

Land Rover’s history is a long and illustrious one that started in 1948 with the vehicle known simply as Land Rover. Since then, every Land Rover has been engineered and designed to answer the same brief: a powerful 4x4 that combines a sense of comfort with true off-road capabilities to enable drivers and enthusiasts to fulfil their sense of adventure. Land Rover’s foray into the motoring world could justly be described as somewhat unassuming. No one could have predicted how a temporary stop-gap measure for the export hungry Rover company would become a worldwide success…

Слайд 24

CHEDDAR CHEESE

Feeling peckish? Then let us offer you

a nibble of the most famous cheese in the

world. There may be Cheddars made in Ireland, in New Zealand and in Canada, but the original one is named after a little village in the dramatic landscape of the Cheddar Gorge in Somerset.

Слайд 25

CHEDDAR CHEESE

We know of a local cheese named

Cheddar as far back as the late 12th century,

a much older provenance than any of the other renowned cheeses of England. Court account books show Henry II ordering over 10,000lb of Cheddar at a rather favourable one farthing (one-quarter of an old penny) per pound in 1170, as did his son Prince John in the following decade. In these days, cheese was a bespoke affair, being made to order by dairy farmers, rather than being a matter of routine production.

Слайд 26 We should note that it is possible the

cheese was first named after the town in which

it was traditionally sold, as opposed to the region in which it was originally produced. That said, Cheddar has been associated with the West Country as far back as records go. Cows grazing on the Somerset pasturage provided the raw material for the cheese, which was a way of using up excess milk, and the Cheddar Caves - with their constant temperature and humidity - made a perfect place in which to store and mature it (alas, no longer). Not only did Cheddar find favour at the English court, but it soon acquired an international reputation. The one great advantage of all hard cheeses over soft is that they keep better, which is why – no matter what the local speciality may be – hard cheeses are always a firm consumer favourite.

Слайд 27

Bibliography:

The book “1000 English topics” V. Kaverina

and V. Boiko

The book “Brush your English” E.D. Mihailova

and A.Y. Romanovich James O”driscoll “Britain” Oxford University Press, 2006

Anne Collins “British Life” Pearson Education Limited

V.F.Satinova “Read and speak about Britain and the British”, 2000

Speak out “ № 6, 204; №1,205

www.icons.org.uk

www.posternazakaz.ru

www.velikobritaniya.org