- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Introduction to finance

Содержание

- 2. Examination paper format Answer FOUR (4) out

- 3. Question 1 (a) Calculation (10 marks)(b) Theory : Discuss (15

- 4. Question 3Theory : Explain (25 marks) Question 4Theory : Discuss (25 marks)

- 5. Question 5Theory and show calculations to support

- 6. The Goal of the FirmThe goal of

- 7. 3 Roles of Finance in BusinessWhat long-term

- 8. Role of the Financial Manager

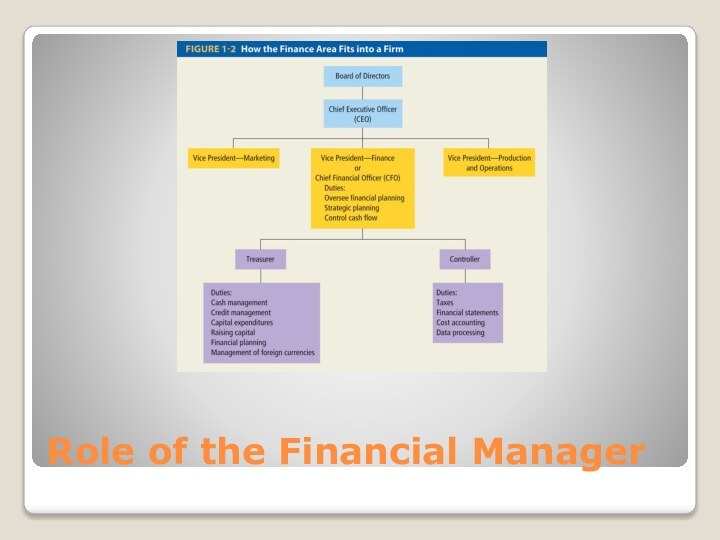

- 9. Legal Forms of Business Organization

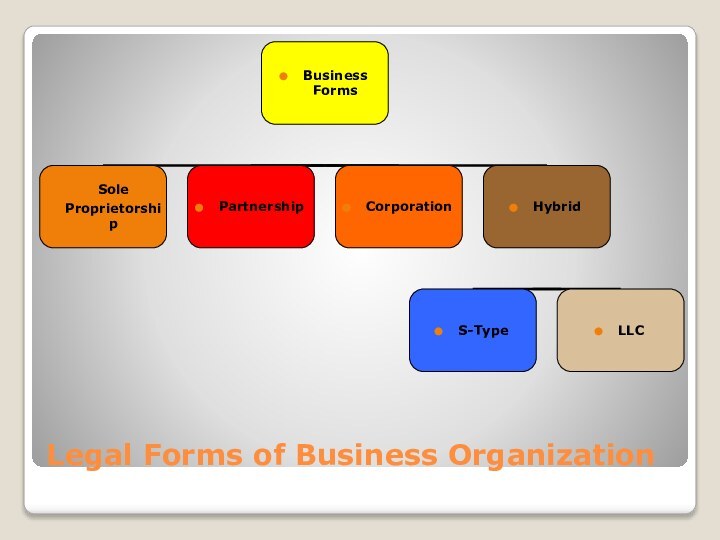

- 10. Sole ProprietorshipBusiness owned by an individualOwner maintains

- 11. PartnershipTwo or more persons come together as

- 12. CorporationLegally functions separate and apart from its

- 13. Hybrid Organizations: S-CorporationBenefitsLimited liabilityTaxed as partnership (no

- 14. Hybrid Organizations: Limited Liability Companies (LLCs)BenefitsLimited

- 15. Finance and The Multinational Firm: The New

- 16. Why Do Companies Go Abroad?To increase revenuesTo

- 17. Risks/Challenges of Going AbroadCountry risk (changes in

- 18. What Is Liquidity? Liquidity is the term

- 19. How Liquid Is the Firm?A liquid asset

- 20. Measuring Liquidity: Perspective 1Compare a firm’s

- 21. Table 4-1

- 22. Table 4-2

- 23. Current RatioCurrent ratio compares a firm’s current

- 24. Acid Test or Quick RatioQuick ratio compares

- 25. Measuring Liquidity: Perspective 2Measures a firm’s ability

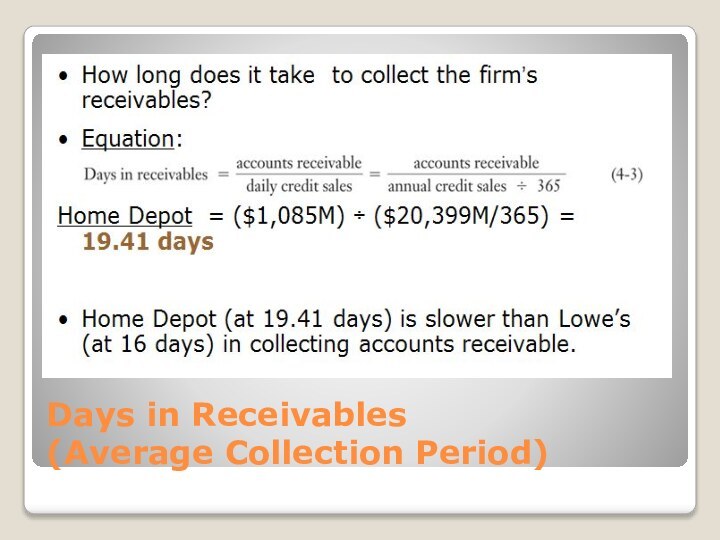

- 26. Days in Receivables (Average Collection Period)

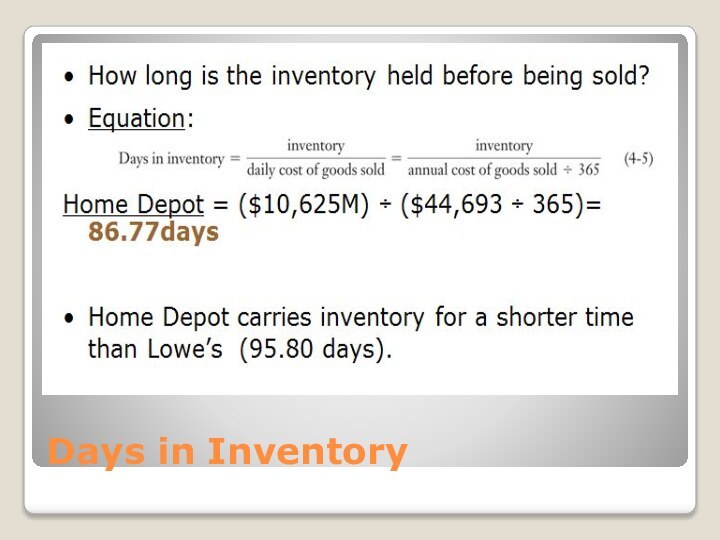

- 27. Days in Inventory

- 28. Certificates of deposit are slightly less liquid, because

- 29. Each of the above can be considered

- 30. Other examples are items like coins, stamps,

- 31. Cash is a company's lifeblood. In other

- 32. Depending on the industry, companies with good

- 33. A more stringent measure is the quick ratio,

- 34. One last ratio of note is the debt/equity

- 35. Are the Firm’s Managers Generating Adequate

- 36. Operating Return on Assets (ORA)

- 37. Managing Operations: Operating Profit Margin (OPM)

- 38. Managing Assets: Total Asset Turnover

- 39. Managing Assets: Fixed Asset Turnover

- 40. How Is the Firm Financing Its Assets?Does

- 41. Debt Ratio

- 42. Times Interest EarnedThis ratio indicates the amount

- 43. Are the Firm’s Managers Providing a Good Return on the Capital Provided by the Company’s Shareholders?

- 44. ROEHome Depot = $3,338M ÷ $18,889M =

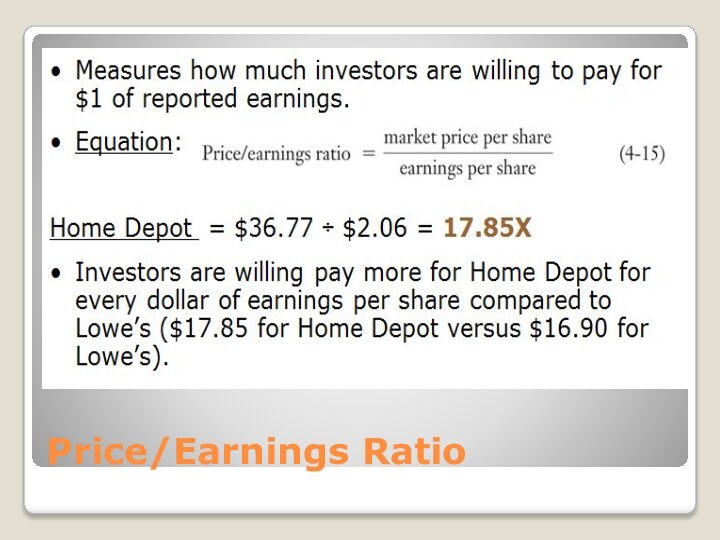

- 45. Price/Earnings Ratio

- 46. Limitations of Financial Ratio AnalysisIt is

- 48. Introduction to FinanceChapter 5 – Stock valuation

- 49. Learning ObjectivesIdentify the basic characteristics of preferred

- 50. Preferred StockPreferred stock is often referred to

- 51. Characteristics of Preferred StocksMultiple series of preferred

- 52. Multiple SeriesIf a company desires, it can

- 53. Claim on Assets and IncomeClaim on Assets:

- 54. Cumulative DividendsCumulative feature (if it exists) requires

- 55. Protective ProvisionsProtective provisions generally allow for voting

- 56. ConvertibilityConvertible preferred stock can, at the discretion

- 57. Retirement ProvisionsAlthough preferred stock has no set

- 58. The economic or intrinsic value of a

- 59. Common StockCommon stock is a certificate that

- 60. Claim on IncomeCommon shareholders have the right

- 61. Claim on AssetsCommon stock has a residual

- 62. Limited LiabilityThe liability of shareholders is limited

- 63. Voting RightsMost often, common stockholders are the

- 64. Preemptive RightsPreemptive right entitles the common shareholder

- 65. Valuing Common StockLike bonds and preferred stock,

- 66. Dividend ModelUnlike preferred stock, common stock dividend

- 67. How Can a Company Grow? Through Infusion

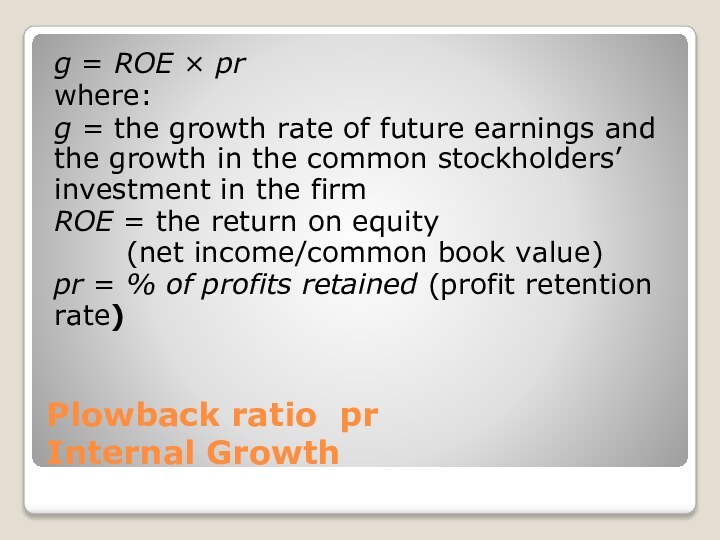

- 68. Plowback ratio pr Internal Growthg = ROE

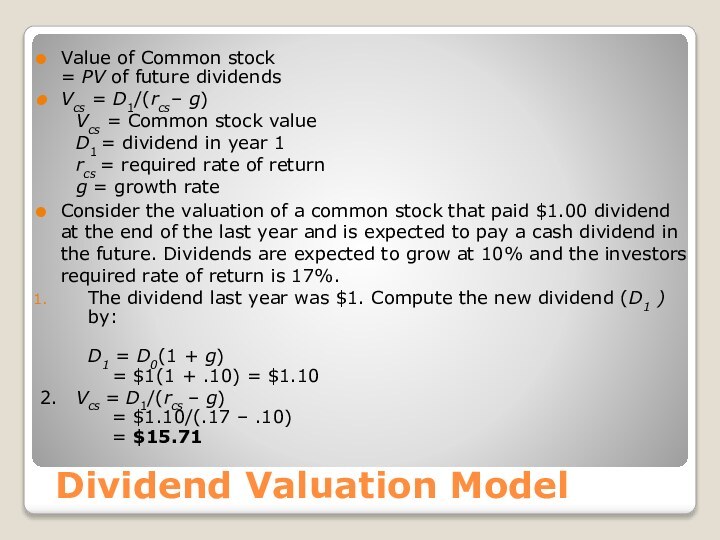

- 69. Dividend Valuation ModelValue of Common stock

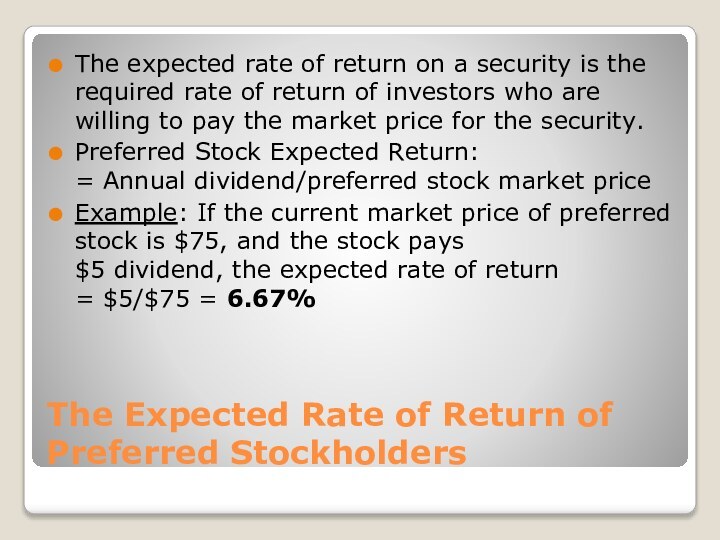

- 70. The Expected Rate of Return of Preferred

- 71. V=D1/(r-g) r-g= D1/P

- 72. Price versus Expected ReturnTypically, an investor is

- 73. BondsMeaning: A bond is a type of

- 74. DebenturesDebentures are unsecured long-term debt.For an issuing

- 75. Subordinated DebenturesThere is a hierarchy of payout

- 76. Mortgage BondsMortgage bond is secured by a

- 77. EurobondsSecurities (bonds) issued in a country different

- 78. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSClaims on Assets

- 79. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSPar ValuePar value

- 80. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSCoupon Interest RateThe

- 81. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSZero Coupon BondsZero

- 82. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSMaturityMaturity of bond

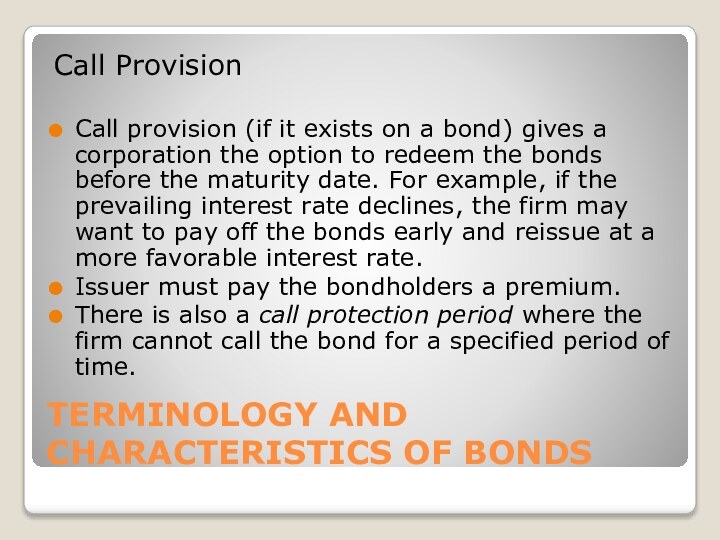

- 83. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSCall ProvisionCall provision

- 84. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSIndentureAn indenture is

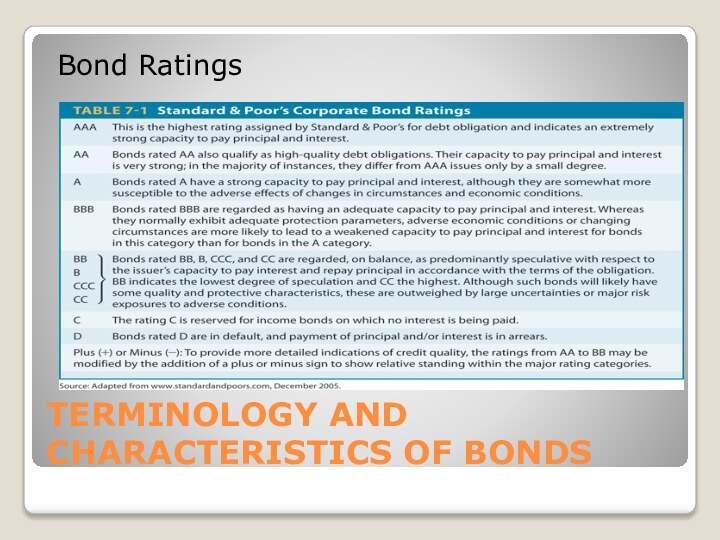

- 85. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSBond RatingsBond ratings

- 86. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSBond Ratings

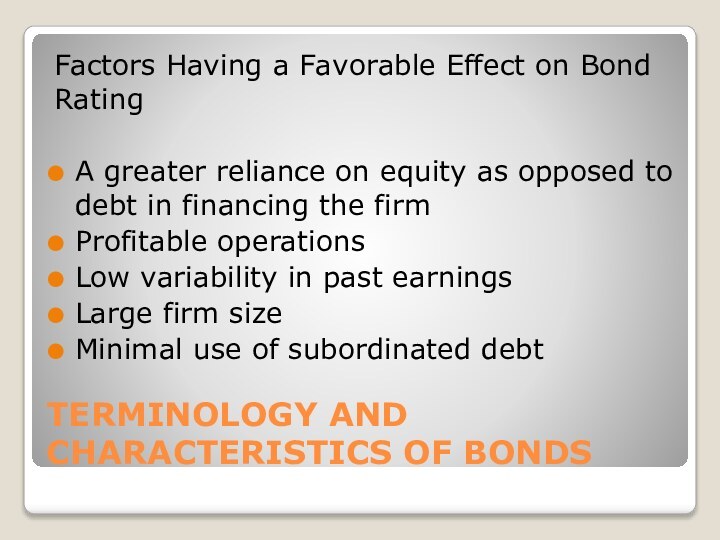

- 87. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSFactors Having a

- 88. TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDSJunk BondsJunk bonds

- 89. CapitalCapital represents the funds used to finance

- 90. Cost of Capital The firm’s cost of capital

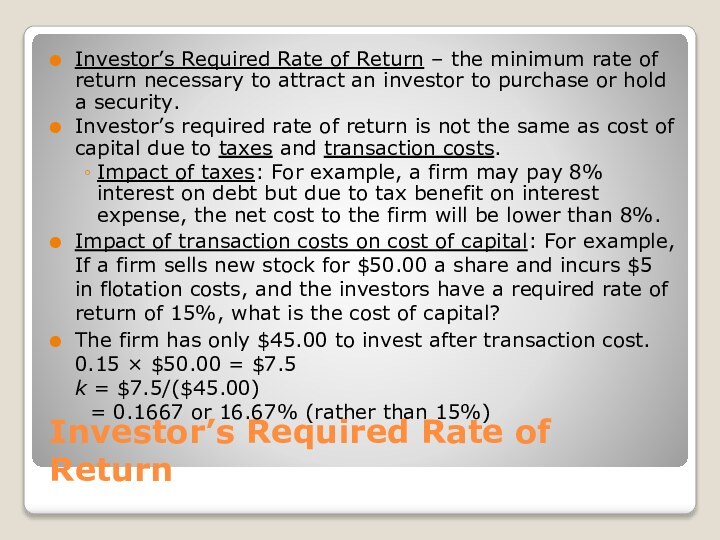

- 91. Investor’s Required Rate of ReturnInvestor’s Required Rate

- 92. Financial PolicyA firm’s financial policy indicates the

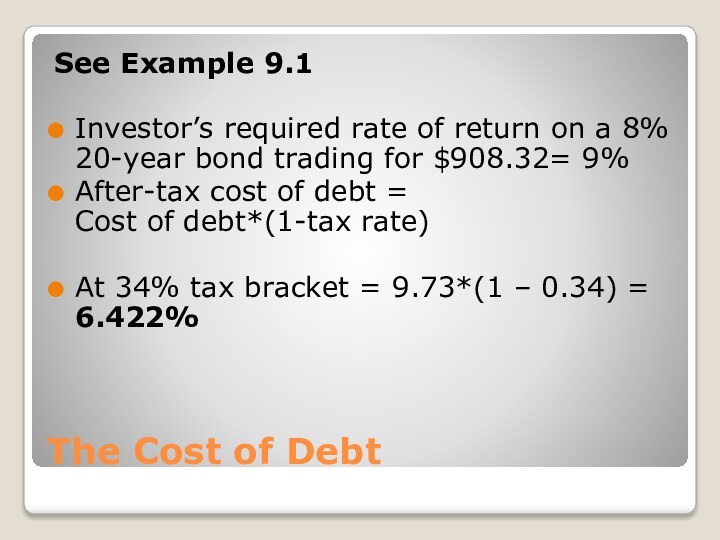

- 93. The Cost of Debt

- 94. The Cost of DebtSee Example 9.1Investor’s required

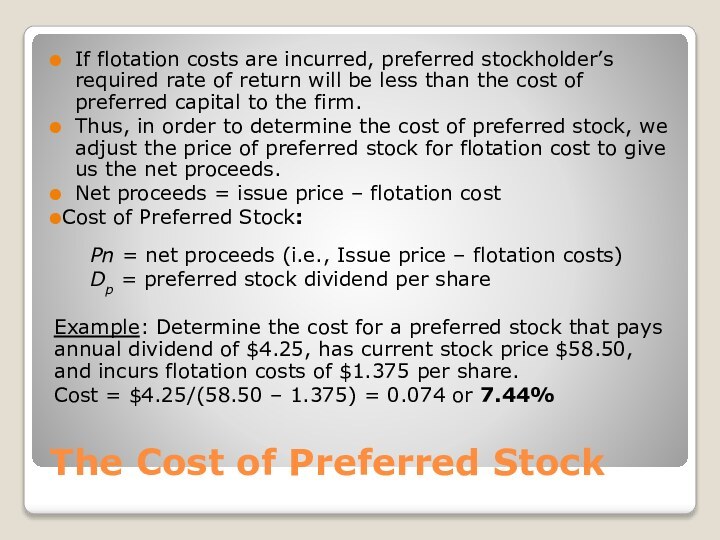

- 95. The Cost of Preferred StockIf flotation costs

- 96. The Cost of Common EquityCost of equity

- 97. Cost Estimation TechniquesTwo commonly used methods for

- 98. The Dividend Growth ModelInvestors’ required rate of

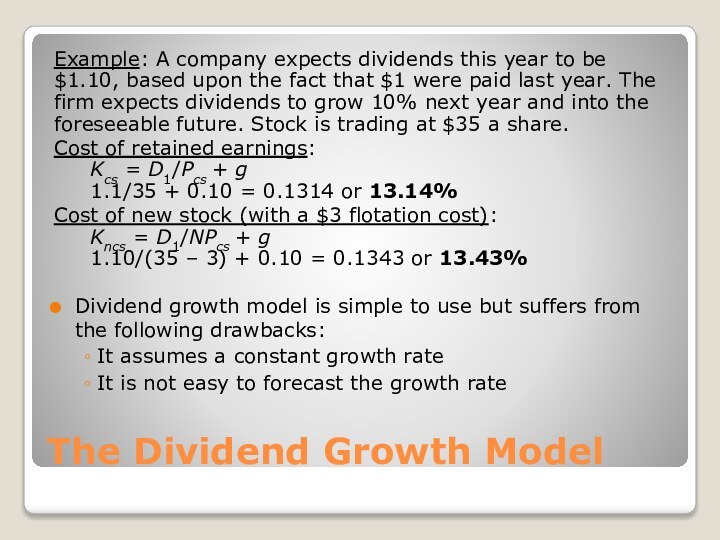

- 99. The Dividend Growth ModelExample: A company expects

- 100. The Capital Asset Pricing Model Example: If

- 101. Capital Asset Pricing Model Variable EstimatesCAPM is

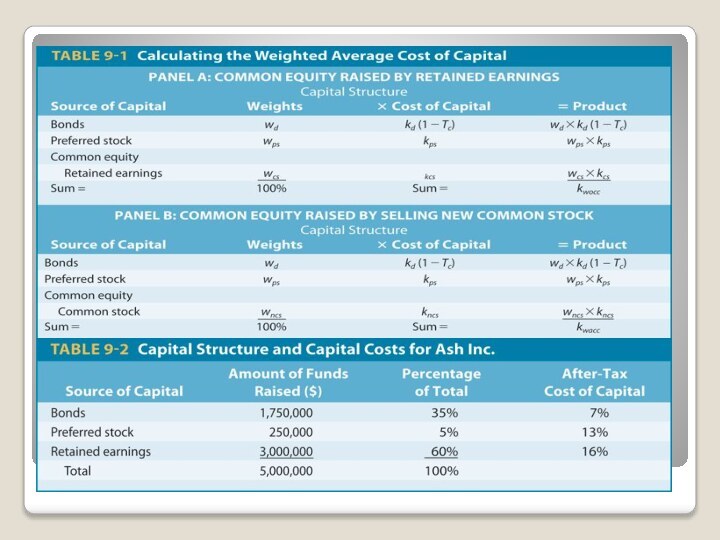

- 102. The Weighted Average Cost of CapitalBringing

- 103. The Weighted Average Cost of Capital

- 104. Business World Cost of capitalIn practice, the

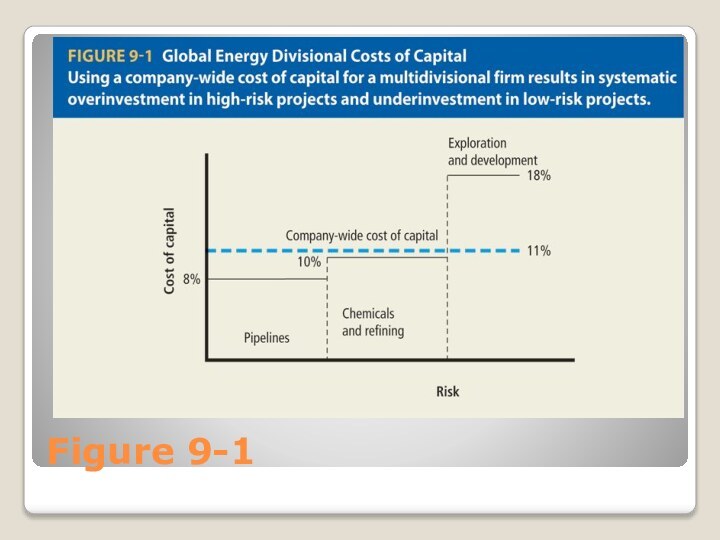

- 107. Divisional Costs of CapitalFirms with multiple operating

- 108. Advantages of Divisional WACCDifferent discount rates reflect

- 109. Using Pure Play Firms to Estimate Divisional

- 110. Divisional WACC ExampleTable 9-4 contains hypothetical estimates

- 111. Divisional WACC – Estimation Issues and LimitationsSample

- 112. Cost of Capital to Evaluate New

- 113. Figure 9-1

- 114. Capital BudgetingMeaning: The process of decision making

- 115. Capital-Budgeting Decision CriteriaThe Payback PeriodNet Present ValueProfitability IndexInternal Rate of Return

- 116. The Payback PeriodMeaning: Number of years needed

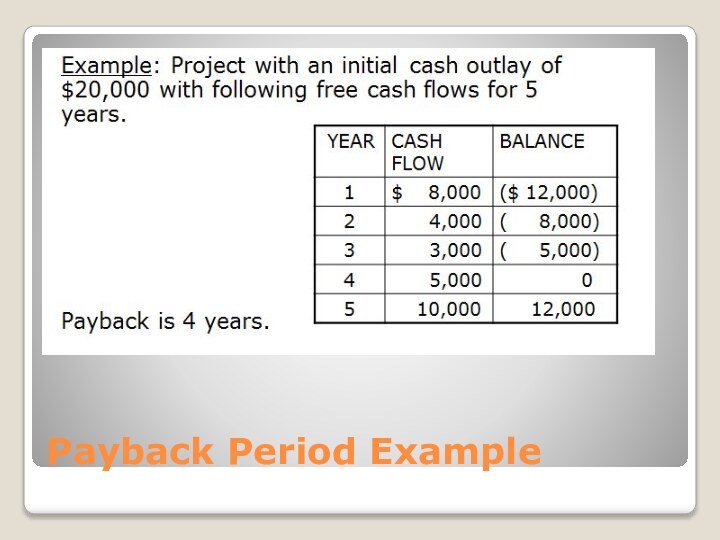

- 117. Payback Period Example

- 118. The Payback Period - Trade-OffsBenefits: Uses cash

- 119. Discounted Payback PeriodThe discounted payback period is

- 120. Discounted Payback PeriodTable 10-2 shows the difference

- 121. Discounted Payback Period

- 122. Net Present Value (NPV)NPV is equal to

- 123. NPV ExampleExample: Project with an initial cash

- 124. NPV Trade-OffsBenefitsConsiders all cash flows Recognizes time

- 125. The Profitability Index (PI) (Benefit-Cost Ratio) The

- 126. Profitability Index

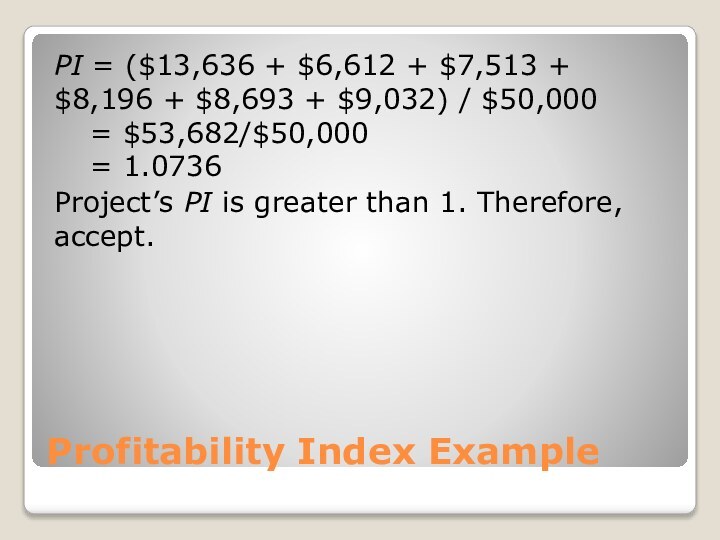

- 127. Profitability Index ExampleA firm with a 10%

- 128. Profitability Index ExamplePI = ($13,636 + $6,612

- 129. NPV and PIWhen the present value of

- 130. Internal Rate of Return (IRR)Decision Rule: If

- 131. Figure 10-1

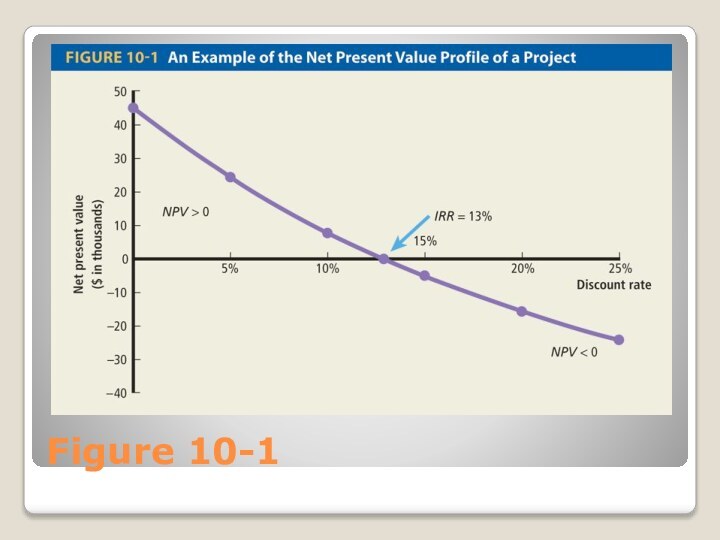

- 132. IRR and NPVIf NPV is positive, IRR

- 133. IRR ExampleInitial Outlay: $3,817Cash flows: Yr. 1

- 134. Guidelines for Capital BudgetingTo evaluate investment proposals,

- 135. Guidelines for Capital BudgetingUse Free Cash Flows

- 136. CALCULATING A PROJECT’S FREE CASH FLOWSThree components

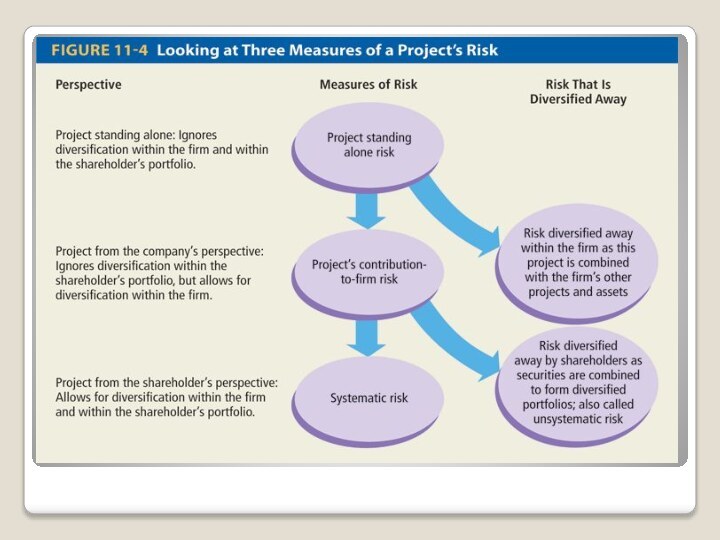

- 137. Three Perspectives on RiskProject standing alone riskProject’s contribution-to-firm riskSystematic risk

- 138. Project Standing Alone RiskThis is a project’s

- 139. Contribution-to-Firm RiskThis is the amount of risk

- 140. Systematic RiskRisk of the project from the

- 142. Relevant RiskTheoretically, the only risk of concern

- 143. Incorporating Risk into Capital BudgetingInvestors demand

- 144. RiskRisk is variability associated with expected revenue

- 145. Business RiskBusiness risk is the variation in

- 146. Operating RiskOperating risk is the variation in

- 147. Financial RiskFinancial risk is the variation in

- 148. Capital Structure TheoryTheory focuses on the effect

- 149. Capital Structure TheoryFigure 12-5 shows that the

- 152. Capital Structure TheoryThe implication of these figures

- 153. Extensions to Independence Hypothesis: The Moderate PositionThe

- 154. Impact of Taxes on Capital StructureInterest expense

- 155. Impact of Taxes on Capital StructureSince interest

- 156. Impact of Bankruptcy on Capital StructureThe probability

- 158. Firm Value and Agency Costs

- 159. Managerial ImplicationsDetermining the firm’s financing mix is

- 160. DividendsDividends are distribution from the firm’s assets

- 161. Dividend PolicyA firm’s dividend policy includes two

- 162. Dividend-versus-Retention Trade-Offs

- 163. DOES DIVIDEND POLICY MATTER TO STOCKHOLDERS?There are

- 164. View #1Dividend policy is irrelevant Irrelevance implies

- 165. View #2High dividends increase stock valueThis position

- 166. View #3Low dividend increases stock values In

- 167. Some Other ExplanationsThe Residual Dividend TheoryClientele EffectThe Information EffectAgency CostsThe Expectations Theory

- 168. Residual Dividend TheoryDetermine the optimal capital budgetDetermine

- 169. The Clientele EffectDifferent groups of investors have

- 170. The Information EffectEvidence shows that large, unexpected

- 171. Agency CostsDividend policy may be perceived as

- 172. The Expectations TheoryExpectation theory suggests that the

- 173. Conclusions on Dividend PolicyHere are some conclusions

- 174. The Dividend Decision in PracticeLegal RestrictionsStatutory restrictions

- 175. The Dividend Decision in Practice - Alternative

- 176. The Dividend Decision in Practice - Alternative

- 177. Dividend Payment ProceduresGenerally, companies pay dividend on

- 178. Important DatesDeclaration date – The date when

- 179. Stock DividendsA stock dividend entails the distribution

- 180. Stock SplitsA stock split involves exchanging more

- 181. Stock RepurchasesA stock repurchase (stock buyback) occurs

- 182. Stock Repurchase -- BenefitsA means of providing

- 183. A Share Repurchase as a Dividend, Financing,

- 184. Unsecured Sources: Trade CreditTrade credit arises spontaneously

- 186. Effective Cost of Passing Up a

- 187. Unsecured Sources: Bank CreditCommercial banks provide

- 188. Line of CreditInformal agreement between a borrower

- 189. Revolving CreditRevolving credit is a variant of

- 190. Transaction LoansA transaction loan is made for

- 191. Unsecured Sources: Commercial PaperThe largest and

- 192. Commercial Paper: AdvantagesInterest ratesRates are generally lower

- 193. Secured Sources of LoansSecured loans have assets

- 194. Pledging Accounts ReceivableBorrower pledges accounts receivable as

- 195. Pledging Accounts ReceivableCredit Terms: Interest rate is

- 196. Pledging Accounts ReceivableFactoring accounts receivable involves the

- 197. Secured Sources: Inventory LoansThese are loans

- 198. Types of Inventory LoansFloating or Blanket Lien

- 199. Working CapitalWorking capital - The firm’s total

- 200. Managing Net Working CapitalManaging net working capital

- 201. How Much Short-Term Financing Should a Firm

- 202. The Appropriate Level of Working CapitalManaging working

- 203. The Hedging PrincipleThe hedging principle involves matching

- 205. Permanent and Temporary AssetsPermanent investments Investments that

- 206. Temporary and Permanent Sources of FinancingTemporary sources

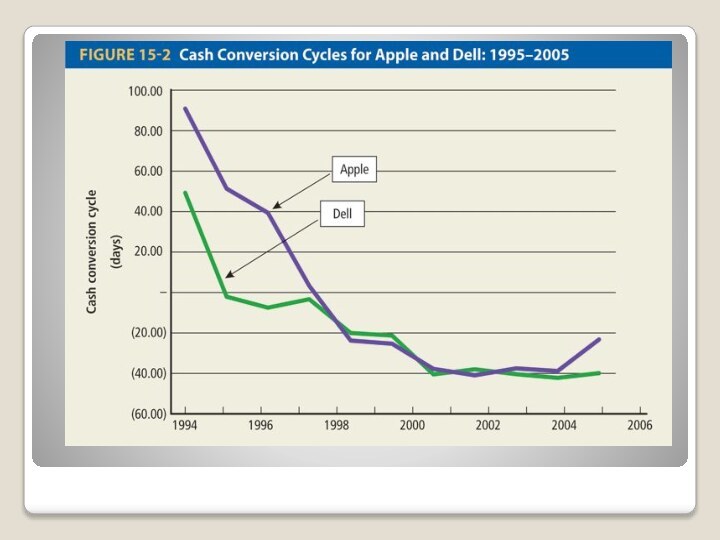

- 208. The Cash Conversion CycleA firm can minimize

- 211. Cost of Short-Term Credit

- 212. APR exampleA company plans to borrow $1,000

- 213. Annual Percentage Yield (APY)APR does not consider

- 214. APY exampleIn the previous example, # of compounding

- 215. Скачать презентацию

- 216. Похожие презентации

Examination paper format Answer FOUR (4) out of SIX (6) questionsEach question has a weighting of 25 marks.

Слайд 3

Question 1

(a) Calculation (10 marks)

(b) Theory : Discuss (15 marks)

(25

marks)

Question 2

(a) Calculation (13 marks)

(b) Theory : Discuss (12 marks)

(25 marks)

Слайд 5

Question 5

Theory and show calculations to support theory:

Evaluate and analyze and discuss

(25 marks)Question 6

a) Calculations (12 marks)

b) Calculations (5 marks)

c) Theory : Discuss (8 marks)

(25 marks)

Слайд 6

The Goal of the Firm

The goal of the

firm is to create value for the firm’s legal

owners (that is, its shareholders). Thus the goal of the firm is to “maximize shareholder wealth” by maximizing the price of the existing common stock.Good financial decisions will increase stock price and poor financial decisions will lead to a decline in stock price.

Слайд 7

3 Roles of Finance in Business

What long-term investments

should the firm undertake? (Capital budgeting decision)

How should the

firm raise money to fund these investments? (Capital structure decision)How to manage cash flows arising from day-to-day operations? (Working capital decision)

Слайд 10

Sole Proprietorship

Business owned by an individual

Owner maintains title

to assets and profits

Unlimited liability

Termination occurs on owner’s death

or by the owner’s choice

Слайд 11

Partnership

Two or more persons come together as co-owners

General

Partnership: All partners are fully responsible for liabilities incurred

by the partnership.Limited Partnerships: One or more partners can have limited liability, restricted to the amount of capital invested in the partnership. There must be at least one general partner with unlimited liability. Limited partners cannot participate in the management of the business and their names cannot appear in the name of the firm.

Слайд 12

Corporation

Legally functions separate and apart from its owners

Corporation

can sue, be sued, purchase, sell, and own property

Owners

(shareholders) dictate direction and policies of the corporation, oftentimes through elected board of directors. Shareholder’s liability is restricted to amount of investment in company.

Life of corporation does not depend on the owners … corporation continues to be run by managers after transfer of ownership through sale or inheritance.

Слайд 13

Hybrid Organizations: S-Corporation

Benefits

Limited liability

Taxed as partnership (no double

taxation like corporations)

Limitations

Owners must be people so cannot be

used for a joint ventures between two corporations

Слайд 14

Hybrid Organizations:

Limited Liability Companies (LLCs)

Benefits

Limited liability

Taxed like

a partnership

Limitations

Qualifications vary from state to state

Cannot appear

like a corporation otherwise it will be taxed like one

Слайд 15

Finance and The Multinational Firm: The New Role

U.S.

firms are looking to international expansion to discover profits.

For example, Coca-Cola earns over 80% of its profits from overseas sales.In addition to US firms going abroad, we have also witnessed many foreign firms making their mark in the United States. For example, domination of auto industry by Honda, Toyota, and Nissan.

Слайд 16

Why Do Companies Go Abroad?

To increase revenues

To reduce

expenses (land, labor, capital, raw material, taxes)

To lower governmental

regulation standards (ex. environmental, labor)To increase global exposure

Слайд 17

Risks/Challenges of Going Abroad

Country risk (changes in government

regulations, unstable government, economic changes in foreign country)

Currency risk

(fluctuations in exchange rates)Cultural risk (differences in language, traditions, ethical standards, etc.)

Слайд 18

What Is Liquidity?

Liquidity is the term used to

describe how easy it is to convert assets to

cash. The most liquid asset, and what everything else is compared to, is cash. This is because it can always be used easily and immediately.

Слайд 19

How Liquid Is the Firm?

A liquid asset is

one that can be converted quickly and routinely into

cash at the current market price.Liquidity measures the firm’s ability to pay its bills on time. It indicates the ease with which non-cash assets can be converted to cash to meet the financial obligations.

Liquidity is measured by two approaches:

Comparing the firm’s current assets and current liabilities

Examining the firm’s ability to convert accounts receivables and inventory into cash on a timely basis

Слайд 20

Measuring Liquidity:

Perspective 1

Compare a firm’s current assets

with current liabilities using:

Current Ratio

Acid Test or Quick Ratio

Слайд 23

Current Ratio

Current ratio compares a firm’s current assets

to its current liabilities.

Equation:

Home Depot = $13,479M ÷ $10,122M

= 1.33Home Depot has $1.33 in current assets for every $1 in current liabilities. Home Depot’s liquidity is marginally lower than that of Lowe’s, which has a current ratio of 1.40.

Слайд 24

Acid Test or Quick Ratio

Quick ratio compares cash

and current assets (minus inventory) that can be converted

into cash during the year with the liabilities that should be paid within the year.Equation:

Home Depot = ($545M + $1,085M) ÷ ( $10,122M) = 0.16

Home Depot has 16 cents in quick assets for every $1 in current debt. Home Depot is more liquid than Lowe’s, which has 12 cents for every $1 in current debt.

Слайд 25

Measuring Liquidity:

Perspective 2

Measures a firm’s ability to convert

accounts receivable and inventory into cash:

Average Collection Period

Inventory Turnover

Слайд 28

Certificates of deposit are slightly less liquid, because there

is usually a penalty for converting them to cash

before their maturity date. Savings bonds are also quite liquid, since they can be sold at a bank fairly easily. Finally, shares of stock, bonds, options and commodities are considered fairly liquid, because they can usually be sold readily and you can receive the cash within a few days.

Слайд 29

Each of the above can be considered as

cash or cash equivalents because they can be converted

to cash with little effort, although sometimes with a slight penalty. (For related reading, see The Money Market.)Moving down the scale, we run into assets that take a bit more effort or time before they can be realized as cash. One example would be preferred orrestricted shares, which usually have covenants dictating how and when they might be sold.

Слайд 30

Other examples are items like coins, stamps, art

and other collectibles. If you were to sell to

another collector, you might get full value but it could take a while, even with the internet easing the way. If you go to a dealer instead, you could get cash more quickly, but you may receive less of it.

Слайд 31

Cash is a company's lifeblood. In other words,

a company can sell lots of widgets and have

good net earnings, but if it can't collect the actual cash from its customers on a timely basis, it will soon fold up, unable to pay its own obligations.Several ratios look at how easily a company can meet its current obligations. One of these is the current ratio, which compares the level of current assets to current liabilities. Remember that in this context, "current" means collectible or payable within one year.

Слайд 32

Depending on the industry, companies with good liquidity

will usually have a current ratio of more than

two. This shows that a company has the resources on hand to meet its obligations and is less likely to borrow money or enter bankruptcy.

Слайд 33

A more stringent measure is the quick ratio, sometimes

called the acid test ratio. This uses current assets

(excluding inventory) and compares them to current liabilities. Inventory is removed because, of the various current assets such as cash, short-term investments or accounts receivable, this is the most difficult to convert into cash. A value of greater than one is usually considered good from a liquidity viewpoint, but this is industry dependent.

Слайд 34

One last ratio of note is the debt/equity ratio,

usually defined as total liabilities divided by stockholders' equity. While

this does not measure a company's liquidity directly, it is related. Generally, companies with a higher debt/equity ratio will be less liquid, as more of their available cash must be used to service and reduce the debt. This leaves less cash for other purposes.Слайд 35 Are the Firm’s Managers Generating Adequate Operating Profits

from the Company’s Assets?

The focus is on the profitability

of the assets in which the firm has invested. The following ratios are considered:Operating Return on Assets

Operating Profit Margin

Total Asset Turnover

Fixed Assets Turnover

Слайд 40

How Is the Firm Financing Its Assets?

Does the

firm finance its assets by debt or equity or

both?The following two ratios are considered:

Debt Ratio

Times Interest Earned

Слайд 42

Times Interest Earned

This ratio indicates the amount of

operating income available to service interest payments.

Equation: Times Interest

Earned = Operating Profits ÷ Interest ExpenseHome Depot = $5,803M ÷ $530M = 10.9X

Home Depot’s operating income is nearly 11 times the annual interest expense and higher than Lowe’s (9X) due to its relatively higher operating profits.

Note:

Interest is not paid with income but with cash.

Oftentimes, firms are required to repay part of the principal annually.

Thus, times interest earned is only a crude measure of the firm’s capacity to service its debt.

Слайд 43 Are the Firm’s Managers Providing a Good Return

on the Capital Provided by the Company’s Shareholders?

Слайд 44

ROE

Home Depot = $3,338M ÷ $18,889M

= 0.177

or 17.7%

Owners of Home Depot are receiving a higher

return (17.7%) compared to Lowe’s (11.1%). One of the reasons for higher ROE is the higher return on assets generated by Home Depot.

Also, Home Depot uses more debt. Higher debt translates to higher ROE under favorable business conditions.

Слайд 46

Limitations of

Financial Ratio Analysis

It is sometimes difficult

to identify industry categories or comparable peers.

The published peer

group or industry averages are only approximations.Industry averages may not provide a desirable target ratio.

Accounting practices differ widely among firms.

A high or low ratio does not automatically lead to a specific conclusion.

Seasons may bias the numbers in the financial statements.

Слайд 49

Learning Objectives

Identify the basic characteristics of preferred stock.

Value

preferred stock.

Identify the basic characteristics of common stock.

Value common

stock.Calculate a stock’s expected rate of return.

Слайд 50

Preferred Stock

Preferred stock is often referred to as

a hybrid security because it has many characteristics of

both common stock and bonds.Hybrid Nature of Preferred Stocks

Like common stocks, preferred stocks

have no fixed maturity date

failure to pay dividends does not lead to bankruptcy

dividends are not a tax-deductible expense

Like Bonds

dividends are fixed in amount (either as a $ amount or as a % of par value)

Слайд 51

Characteristics of Preferred Stocks

Multiple series of preferred stock

Preferred

stock’s claim on assets and income

Cumulative dividends

Protective provisions

Convertibility

Retirement provisions

Слайд 52

Multiple Series

If a company desires, it can issue

more than one series of preferred stock, and each

series can have different characteristics (such as different protective provisions and convertibility rights).

Слайд 53

Claim on Assets and Income

Claim on Assets: Preferred

stock has priority over common stock with regard to

claim on assets in the case of bankruptcy.Preferred stockholders claims are honored before common stockholders, but after bonds.

Claim on Income: Preferred stock also has priority over common stock with regard to dividend payments.

Thus preferred stocks are safer than common stock but riskier than bonds.

Слайд 54

Cumulative Dividends

Cumulative feature (if it exists) requires that

all past, unpaid preferred stock dividends be paid before

any common stock dividends are declared.

Слайд 55

Protective Provisions

Protective provisions generally allow for voting rights

in the event of nonpayment of dividends, or they

restrict the payment of common stock dividends if sinking-funds payments are not met or if the firm is in financial difficulty.These protective provisions reduce the risk and consequently, expected return.

Слайд 56

Convertibility

Convertible preferred stock can, at the discretion of

the holder, be converted into a predetermined number of

shares of common stock.Almost one-third of preferred stock issued today is convertible preferred.

Слайд 57

Retirement Provisions

Although preferred stock has no set maturity

associated with it, issuing firms generally provide for some

method of retiring the stock such as a call provision or sinking fund provision.Call provision entitles the corporation to repurchase its preferred stock at stated prices over a given time period.

Sinking fund provision requires the firm to set aside an amount of money for the retirement of its preferred stock.

Слайд 58 The economic or intrinsic value of a preferred

stock is equal to the present value of all

future dividends.Value of preferred stock: = Annual dividend/required rate of return

V=3.75(1+0.03)/(0.06-0.03)=128.75

Слайд 59

Common Stock

Common stock is a certificate that indicates

ownership in a corporation. When you buy a share,

you buy a “part/share” of the company and attain ownership rights in proportion to your “share” of the company.Common stockholders are the true owners of the firm. Bondholders and preferred stock holders can be viewed as creditors.

Слайд 60

Claim on Income

Common shareholders have the right to

residual income after bondholders and preferred stockholders have been

paid.Residual income can be paid in the form of dividends or retained within the firm and reinvested in the business.

Claim on residual income implies there is no upper limit on income, but it also means that, on the downside, shareholders are not guaranteed anything and may have to settle for zero income in some years.

Слайд 61

Claim on Assets

Common stock has a residual claim

on assets in the case of liquidation.

Residual claim

implies that the claims of debt holders and preferred stockholders have to be met prior to common stockholders.Generally, if bankruptcy occurs, claims of the common shareholders are typically not satisfied.

Слайд 62

Limited Liability

The liability of shareholders is limited to

the amount of their investment.

The limited liability helps

the firm in raising funds.

Слайд 63

Voting Rights

Most often, common stockholders are the only

security holders with a vote.

Majority of shareholders generally

vote by proxy. Proxy fights are battles between rival groups for proxy votes.Common shareholders are entitled to:

elect the board of directors

approve any change in the corporate charter

Voting for directors and charter changes occur at the corporation’s annual meeting.

With majority voting – each share of stock allows the shareholder one vote. Each position on the board is voted on separately.

With cumulative voting - each share of stock allows the stockholder a number of votes equal to the number of directors being elected.

Слайд 64

Preemptive Rights

Preemptive right entitles the common shareholder to

maintain a proportionate share of ownership in the firm.

Thus,

if a shareholder currently owns 5% of the shares, s/he has the right to purchase 5% of the shares when new shares are issued.These rights are issued in the form of certificates that give shareholders the option to buy new shares at a specific price during a 2- to 10- week period. These rights can be exercised, sold in the open market, or allowed to expire.

Слайд 65

Valuing Common Stock

Like bonds and preferred stock, the

value of common stock is equal to the present

value of all future expected cash flows (i.e., dividends).However, dividends are neither fixed nor guaranteed, which makes it harder to value common stocks compared to bonds and preferred stocks.

Слайд 66

Dividend Model

Unlike preferred stock, common stock dividend is

not fixed.

Dividend pattern varies among firms, but dividends

generally tend to increase with the growth in corporate earnings.V=D1/(r-g)

V(ex-div)

Слайд 67

How Can a Company Grow?

Through Infusion of

capital by borrowing or issuing new common stock.

Through

Internal growth. Management retains some or all of the firm’s profits for reinvestment in the firm, resulting in future earnings growth and value of stock. Internal growth directly affects the existing stockholders and is the only growth factor used for valuation purposes.

Слайд 68

Plowback ratio pr

Internal Growth

g = ROE × pr

where:

g = the growth rate of future earnings and

the growth in the common stockholders’ investment in the firmROE = the return on equity (net income/common book value)

pr = % of profits retained (profit retention rate)

Слайд 69

Dividend Valuation Model

Value of Common stock

= PV

of future dividends

Vcs = D1/(rcs– g)

Vcs = Common stock

value D1 = dividend in year 1

rcs = required rate of return

g = growth rate

Consider the valuation of a common stock that paid $1.00 dividend at the end of the last year and is expected to pay a cash dividend in the future. Dividends are expected to grow at 10% and the investors required rate of return is 17%.

The dividend last year was $1. Compute the new dividend (D1 ) by: D1 = D0(1 + g) = $1(1 + .10) = $1.10

2. Vcs = D1/(rcs – g) = $1.10/(.17 – .10) = $15.71

Слайд 70

The Expected Rate of Return of Preferred Stockholders

The

expected rate of return on a security is the

required rate of return of investors who are willing to pay the market price for the security.Preferred Stock Expected Return: = Annual dividend/preferred stock market price

Example: If the current market price of preferred stock is $75, and the stock pays $5 dividend, the expected rate of return = $5/$75 = 6.67%

Слайд 72

Price versus Expected Return

Typically, an investor is not

concerned with the value of a stock. Rather, investor

would like to know the expected rate of return if the stock is bought at its current market price.Given the price and expected rate of return, investor has to decide if the expected return compensates for the risk.

Слайд 73

Bonds

Meaning: A bond is a type of debt

or long-term promissory note, issued by a borrower, promising

to its holder a predetermined and fixed amount of interest per year and repayment of principal at maturity.Bonds are issued by Corporations, Government, State and Local Municipalities

Слайд 74

Debentures

Debentures are unsecured long-term debt.

For an issuing firm,

debentures provide the benefit of not tying up property

as collateral.For bondholders, debentures are more risky than secured bonds and provide a higher yield than secured bonds.

Слайд 75

Subordinated Debentures

There is a hierarchy of payout in

case of insolvency.

The claims of subordinated debentures are honored

only after the claims of secured debt and unsubordinated debentures have been satisfied.

Слайд 76

Mortgage Bonds

Mortgage bond is secured by a lien

on real property.

Typically, the value of the real property

is greater than that of the bonds issued, providing bondholders a margin of safety.

Слайд 77

Eurobonds

Securities (bonds) issued in a country different from

the one in whose currency the bond is denominated.

For example, a bond issued by an American corporation in Japan that pays interest and principal in dollars.

Слайд 78

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Claims on Assets and

Income

Seniority in claims

In the case of insolvency, claims

of debt, including bonds, are generally honored before those of common or preferred stock.

Слайд 79

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Par Value

Par value is

the face value of the bond, returned to the

bondholder at maturity.In general, corporate bonds are issued at denominations or par value of $1,000.

Prices are represented as a % of face value. Thus, a bond quoted at 112 can be bought at 112% of its par value in the market. Bonds will return the par value at maturity, regardless of the price paid at the time of purchase.

Слайд 80

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Coupon Interest Rate

The percentage

of the par value of the bond that will

be paid periodically in the form of interest.Example: A bond with a $1,000 par value and 5% annual coupon rate will pay $50 annually (=0.05*1000) or $25 (if interest is paid semiannually).

Слайд 81

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Zero Coupon Bonds

Zero coupon

bonds have zero or very low coupon rate. Instead

of paying interest, the bonds are issued at a substantial discount below the par or face value.

Слайд 82

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Maturity

Maturity of bond refers

to the length of time until the bond issuer

returns the par value to the bondholder and terminates or redeems the bond.

Слайд 83

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Call Provision

Call provision (if

it exists on a bond) gives a corporation the

option to redeem the bonds before the maturity date. For example, if the prevailing interest rate declines, the firm may want to pay off the bonds early and reissue at a more favorable interest rate.Issuer must pay the bondholders a premium.

There is also a call protection period where the firm cannot call the bond for a specified period of time.

Слайд 84

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Indenture

An indenture is the

legal agreement between the firm issuing the bond and

the trustee who represents the bondholders.It provides for specific terms of the loan agreement (such as rights of bondholders and issuing firm).

Many of the terms seek to protect the status of bonds from being weakened by managerial actions or by other security holders.

Слайд 85

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Bond Ratings

Bond ratings reflect

the future risk potential of the bonds.

Three prominent bond

rating agencies are Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Investor Services. Lower bond rating indicates higher probability of default. It also means that the rate of return demanded by the capital markets will be higher on such bonds.

Слайд 87

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Factors Having a Favorable

Effect on Bond Rating

A greater reliance on equity as

opposed to debt in financing the firmProfitable operations

Low variability in past earnings

Large firm size

Minimal use of subordinated debt

Слайд 88

TERMINOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS OF BONDS

Junk Bonds

Junk bonds are

high-risk bonds with ratings of BB or below by

Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s.Junk bonds are also referred to as high-yield bonds as they pay a high interest rate, generally 3 to 5% more than AAA-rated bonds.

Слайд 89

Capital

Capital represents the funds used to finance a

firm's assets and operations. Capital constitutes all items on

the right hand side of balance sheet, i.e., liabilities and common equity.Main sources: Debt, Preferred stock, Retained earnings and Common Stock

Слайд 90

Cost of Capital

The firm’s cost of capital is

also referred to as the firm’s Opportunity cost of

capital.

Слайд 91

Investor’s Required Rate of Return

Investor’s Required Rate of

Return – the minimum rate of return necessary to

attract an investor to purchase or hold a security.Investor’s required rate of return is not the same as cost of capital due to taxes and transaction costs.

Impact of taxes: For example, a firm may pay 8% interest on debt but due to tax benefit on interest expense, the net cost to the firm will be lower than 8%.

Impact of transaction costs on cost of capital: For example, If a firm sells new stock for $50.00 a share and incurs $5 in flotation costs, and the investors have a required rate of return of 15%, what is the cost of capital?

The firm has only $45.00 to invest after transaction cost. 0.15 × $50.00 = $7.5 k = $7.5/($45.00) = 0.1667 or 16.67% (rather than 15%)

Слайд 92

Financial Policy

A firm’s financial policy indicates the desired

sources of financing and the particular mix in which

it will be used.For example, a firm may choose to raise capital by issuing stocks and bonds in the ratio of 6:4 (60% stocks and 40% bonds). The choice of mix will impact the cost of capital.

Слайд 94

The Cost of Debt

See Example 9.1

Investor’s required rate

of return on a 8% 20-year bond trading for

$908.32= 9%After-tax cost of debt = Cost of debt*(1-tax rate)

At 34% tax bracket = 9.73*(1 – 0.34) = 6.422%

Слайд 95

The Cost of Preferred Stock

If flotation costs are

incurred, preferred stockholder’s required rate of return will be

less than the cost of preferred capital to the firm.Thus, in order to determine the cost of preferred stock, we adjust the price of preferred stock for flotation cost to give us the net proceeds.

Net proceeds = issue price – flotation cost

Cost of Preferred Stock:

Pn = net proceeds (i.e., Issue price – flotation costs)

Dp = preferred stock dividend per share

Example: Determine the cost for a preferred stock that pays annual dividend of $4.25, has current stock price $58.50, and incurs flotation costs of $1.375 per share.

Cost = $4.25/(58.50 – 1.375) = 0.074 or 7.44%

Слайд 96

The Cost of Common Equity

Cost of equity is

more challenging to estimate than the cost of debt

or the cost of preferred stock because common stockholder’s rate of return is not fixed as there is no stated coupon rate or dividend.Furthermore, the costs will vary for two sources of equity (i.e., retained earnings and new issue).

There are no flotation costs on retained earnings but the firm incurs costs when it sells new common stock.

Note that retained earnings are not a free source of capital. There is an opportunity cost.

Слайд 97

Cost Estimation Techniques

Two commonly used methods for estimating

common stockholder’s required rate of return are:

The Dividend Growth

ModelThe Capital Asset Pricing Model

Слайд 98

The Dividend Growth Model

Investors’ required rate of return

(For Retained Earnings):

D1 = Dividends expected one year hence

Pcs

= Price of common stock g = growth rate

Investors’ required rate of return (For new issues)

D1 = Dividends expected one year hence

Pcs = Net proceeds per share

g = growth rate

Слайд 99

The Dividend Growth Model

Example: A company expects dividends

this year to be $1.10, based upon the fact

that $1 were paid last year. The firm expects dividends to grow 10% next year and into the foreseeable future. Stock is trading at $35 a share.Cost of retained earnings:

Kcs = D1/Pcs + g

1.1/35 + 0.10 = 0.1314 or 13.14%

Cost of new stock (with a $3 flotation cost):

Kncs = D1/NPcs + g

1.10/(35 – 3) + 0.10 = 0.1343 or 13.43%

Dividend growth model is simple to use but suffers from the following drawbacks:

It assumes a constant growth rate

It is not easy to forecast the growth rate

Слайд 100

The Capital Asset Pricing Model

Example: If beta

is 1.25, risk-free rate is 1.5% and expected return

on market is 10%kc = rrf + β(rm – rf)

= 0.015 + 1.25(0.10 – 0.015)

= 12.125%

Слайд 101

Capital Asset Pricing Model Variable Estimates

CAPM is easy

to apply. Also, the estimates for model variables are

generally available from public sources.Risk-Free Rate: Wide range of U.S. government securities on which to base risk-free rate

Beta: Estimates of beta are available from a wide range of services, or can be estimated using regression analysis of historical data.

Market Risk Premium: It can be estimated by looking at history of stock returns and premium earned over risk-free rate.

Слайд 102

The Weighted Average

Cost of Capital

Bringing it all

together: WACC

To estimate WACC, we need to know the

capital structure mix and the cost of each of the sources of capital.For a firm with only two sources: debt and common equity,

Слайд 104

Business World Cost of capital

In practice, the calculation

of cost of capital may be more complex:

If firms

have multiple debt issues with different required rates of return.If firms also use preferred stock in addition to common stock financing.

Слайд 107

Divisional Costs of Capital

Firms with multiple operating divisions

often have unique risks and different costs of capital

for each division.Consequently, the WACC used in each division is potentially unique for each division.

Слайд 108

Advantages of Divisional WACC

Different discount rates reflect differences

in the systematic risk of the projects evaluated by

different divisions.It entails calculating one cost of capital for each division (rather than each project).

Divisional cost of capital limits managerial latitude and the attendant influence costs.

Слайд 109

Using Pure Play Firms to Estimate Divisional WACCs

Divisional

cost of capital can be estimated by identifying “pure

play” comparison firms that operate in only one of the individual business areas.For example, Valero Energy Corp. may use the WACC estimate of firms that operate in the refinery industry to estimate the WACC of its division engaged in refining crude oil.

Слайд 110

Divisional WACC Example

Table 9-4 contains hypothetical estimates of

the divisional WACC for the refining and retail (convenience

store) industries.Panel A: Cost of debt (tax=38%)

Panel B: Cost of equity (betas differ)

Panels D & E: Divisional WACCs

Слайд 111

Divisional WACC – Estimation Issues and Limitations

Sample chosen

may not be a good match for the firm

or one of its divisions due to differences in capital structure, and/or project risk.Good comparison firms for a particular division may be difficult to find.

Слайд 112

Cost of Capital to Evaluate

New Capital Investments

Cost

of capital can serve as the discount rate in

evaluating new investment when the projects offer the same risk as the firm as a whole.If risk differs, it is better to calculate a different cost of capital for each division. Figure 9-1 illustrates the danger of not doing so.

Слайд 114

Capital Budgeting

Meaning: The process of decision making with

respect to investments in fixed assets—that is, should a

proposed project be accepted or rejected.It is easier to“evaluate” profitable projects than to“find them”

Source of Ideas for Projects

R&D: Typically, a firm has a research & development (R&D) department that searches for ways of improving existing products or finding new projects.

Other sources: Employees, Competition, Suppliers, Customers.

Слайд 115

Capital-Budgeting Decision Criteria

The Payback Period

Net Present Value

Profitability Index

Internal

Rate of Return

Слайд 116

The Payback Period

Meaning: Number of years needed to

recover the initial cash outlay related to an investment.

Decision

Rule: Project is considered feasible or desirable if the payback period is less than or equal to the firm’s maximum desired payback period. In general, shorter payback period is preferred while comparing two projects.

Слайд 118

The Payback Period - Trade-Offs

Benefits:

Uses cash flows

rather than accounting profits

Easy to compute and understand

Useful for

firms that have capital constraintsDrawbacks:

Ignores the time value of money

Does not consider cash flows beyond the payback period

Слайд 119

Discounted Payback Period

The discounted payback period is similar

to the traditional payback period except that it uses

discounted free cash flows rather than actual undiscounted cash flows.The discounted payback period is defined as the number of years needed to recover the initial cash outlay from the discounted free cash flows.

Слайд 120

Discounted Payback Period

Table 10-2 shows the difference between

traditional payback and discounted payback methods.

With undiscounted free cash

flows,

the payback period is only 2 years,

while with discounted free cash flows (at 17%), the discounted payback period is 3.07 years.

Слайд 122

Net Present Value (NPV)

NPV is equal to the

present value of all future free cash flows less

the investment’s initial outlay. It measures the net value of a project in today’s dollars.

Слайд 123

NPV Example

Example: Project with an initial cash outlay

of $60,000 with following free cash flows for 5

years.Year FCF Year FCF

Initial outlay –60,000 3 13,000

1 –25,000 4 12,000

2 –24,000 5 11,000

The firm has a 15% required rate of return.

PV of FCF = $60,764

Subtracting the initial cash outlay of $60,000 leaves an NPV of $764.

Since NPV > 0, project is feasible.

Слайд 124

NPV Trade-Offs

Benefits

Considers all cash flows

Recognizes time value

of money

Drawbacks

Requires detailed long-term forecast of cash flows

NPV is

generally considered to be the most theoretically correct criterion for evaluating capital budgeting projects.

Слайд 125

The Profitability Index (PI)

(Benefit-Cost Ratio)

The profitability index

(PI) is the ratio of the present value of

the future free cash flows (FCF) to the initial outlay.It yields the same accept/reject decision as NPV.

Слайд 127

Profitability Index Example

A firm with a 10% required

rate of return is considering investing in a new

machine with an expected life of six years. The initial cash outlay is $50,000.

Слайд 128

Profitability Index Example

PI = ($13,636 + $6,612 +

$7,513 + $8,196 + $8,693 + $9,032)

/ $50,000= $53,682/$50,000

= 1.0736

Project’s PI is greater than 1. Therefore, accept.

Слайд 129

NPV and PI

When the present value of a

project’s free cash inflows are greater than the initial

cash outlay, the project NPV will be positive. PI will also be greater than 1.NPV and PI will always yield the same decision.

Слайд 130

Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Decision Rule:

If IRR

≥ Required Rate of Return, accept

If IRR < Required

Rate of Return, reject

Слайд 132

IRR and NPV

If NPV is positive, IRR will

be greater than the required rate of return

If NPV

is negative, IRR will be less than required rate of returnIf NPV = 0, IRR is the required rate of return.

Слайд 133

IRR Example

Initial Outlay: $3,817

Cash flows: Yr. 1 =

$1,000, Yr. 2 = $2,000, Yr. 3 = $3,000

Discount rate NPV

15% $4,356

20% $3,958

22% $3,817

IRR is 22% because the NPV equals the initial cash outlay at that rate.

Слайд 134

Guidelines for Capital Budgeting

To evaluate investment proposals, we

must first set guidelines by which we measure the

value of each proposal.We must know what is and what isn’t relevant cash flow.

Слайд 135

Guidelines for Capital Budgeting

Use Free Cash Flows Rather

than Accounting Profits

Think Incrementally

Beware of Cash Flows Diverted From

Existing ProductsLook for Incidental or Synergistic Effects

Work in Working-Capital Requirements

Consider Incremental Expenses

Sunk Costs Are Not Incremental Cash Flows

Account for Opportunity Costs

Decide If Overhead Costs Are Truly Incremental Cash Flows

Ignore Interest Payments and Financing Flows

Слайд 136

CALCULATING A PROJECT’S FREE CASH FLOWS

Three components of

free cash flows:

The initial outlay,

The annual free cash flows

over the project’s life, and The terminal free cash flow

Слайд 137

Three Perspectives on Risk

Project standing alone risk

Project’s contribution-to-firm

risk

Systematic risk

Слайд 138

Project Standing Alone Risk

This is a project’s risk

ignoring the fact that much of the risk will

be diversified away as the project is combined with other projects and assets.This is an inappropriate measure of risk for capital-budgeting projects.

Слайд 139

Contribution-to-Firm Risk

This is the amount of risk that

the project contributes to the firm as a whole.

This measure considers the fact that some of the project’s risk will be diversified away as the project is combined with the firm’s other projects and assets but ignores the effects of the diversification of the firm’s shareholders.

Слайд 140

Systematic Risk

Risk of the project from the viewpoint

of a well-diversified shareholder.

This measure takes into account that

some of the risk will be diversified away as the project is combined with the firm’s other projects and in addition, some of the remaining risk will be diversified away by the shareholders as they combine this stock with other stocks in their portfolios.

Слайд 142

Relevant Risk

Theoretically, the only risk of concern to

shareholders is systematic risk.

Since the project’s contribution-to-firm risk affects

the probability of bankruptcy for the firm, it is a relevant risk measure.Thus we need to consider both the project’s contribution-to-firm risk and the project’s systematic risk.

Слайд 143

Incorporating Risk into

Capital Budgeting

Investors demand higher returns

for more risky projects.

As the risk of a project

increases, the required rate of return is adjusted upward to compensate for the added risk. This risk-adjusted discount rate is then used for discounting free cash flows (in NPV model) or as the benchmark required rate of return (in IRR model).

Слайд 144

Risk

Risk is variability associated with expected revenue or

income streams. Such variability may arise due to:

Choice of

business line (business risk)Choice of an operating cost structure (operating risk)

Choice of a capital structure (financial risk)

Слайд 145

Business Risk

Business risk is the variation in the

firm’s expected earnings attributable to the industry in which

the firm operates. There are four determinants of business risk:The stability of the domestic economy

The exposure to, and stability of, foreign economies

Sensitivity to the business cycle

Competitive pressures in the firm’s industry

Слайд 146

Operating Risk

Operating risk is the variation in the

firm’s operating earnings that results from firm’s cost structure

(mix of fixed and variable operating costs).Earnings of firms with higher proportion of fixed operating costs are more vulnerable to change in revenues.

Слайд 147

Financial Risk

Financial risk is the variation in earnings

as a result of firm’s financing mix or proportion

of financing that requires a fixed return.

Слайд 148

Capital Structure Theory

Theory focuses on the effect of

financial leverage on the overall cost of capital to

the enterprise.In other words, Can the firm affect its overall cost of funds, either favorably or unfavorably, by varying the mixture of financing used?

According to Modigliani & Miller, the total value of the firm is not influenced by the firm’s capital structure. In other words, the financing decision is irrelevant!

Their conclusions were based on restrictive assumptions (such as no taxes, capital structure consisting of only stocks and bonds, perfect or efficient markets).

Firms strive to minimize the cost of using financial capital so as to maximize shareholder’s wealth.

Слайд 149

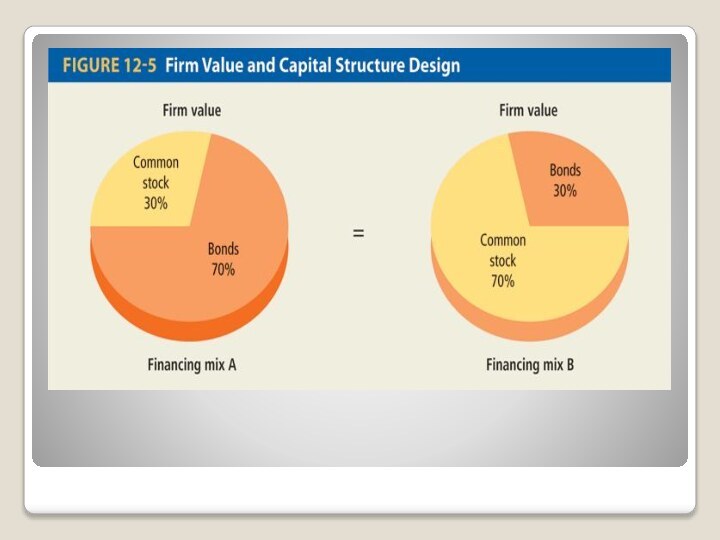

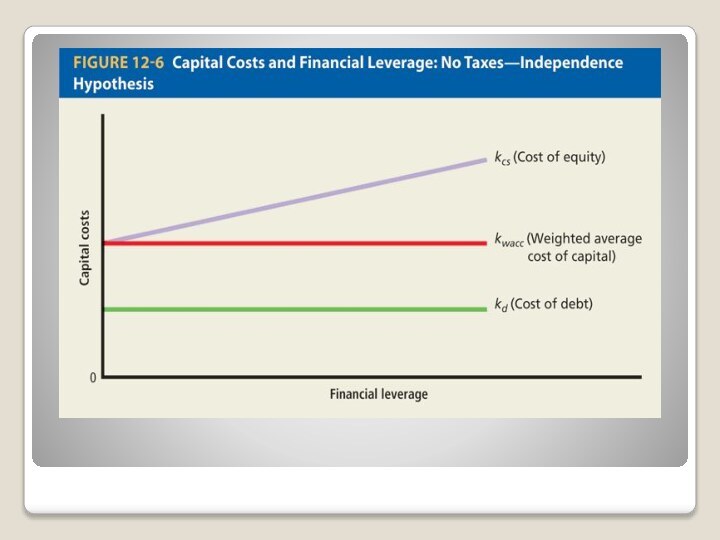

Capital Structure Theory

Figure 12-5 shows that the firm’s

value remains the same, despite the differences in financing

mix.Figure 12-6 shows that the firm’s cost of capital remains constant, although cost of equity rises with increased leverage.

Слайд 152

Capital Structure Theory

The implication of these figures for

financial managers is that one capital structure is just

as good as any other.However, the above conclusion is possible only under strict assumptions.

We next turn to a market and legal environment that relaxes these restrictive assumptions.

Слайд 153

Extensions to Independence Hypothesis: The Moderate Position

The moderate

position considers how the capital structure decision is affected

when we consider:Interest expense is tax deductible (a benefit of debt)

Debt financing increases the risk of default (a disadvantage of debt)

Combining the above (benefit & drawback) provides a conceptual basis for designing a prudent capital structure.

Слайд 154

Impact of Taxes on Capital Structure

Interest expense is

tax deductible.

Because interest is deductible, the use of debt

financing should result in higher total market value for firms outstanding securities.Tax shield benefit = rd(m)(t) r = rate, m = principal, t = marginal tax rate

Слайд 155

Impact of Taxes on Capital Structure

Since interest on

debt is tax deductible, the higher the interest expense,

the lower the taxes.Thus, one could suggest that firms should maximize debt … indeed, firms should go for 100% debt to maximize tax shield benefits!!

But we generally do not see 100% debt in the real world … why not?

One possible explanation is:

Bankruptcy costs

Слайд 156

Impact of Bankruptcy on Capital Structure

The probability that

a firm will be unable to meet its debt

obligations increases with debt. Thus probability of bankruptcy (and hence costs) increase with increased leverage. Threat of financial distress causes the cost of debt to rise.As financial conditions weaken, expected costs of default can be large enough to outweigh the tax shield benefit of debt financing.

So, higher debt does not always lead to a higher value … after a point, debt reduces the value of the firm to shareholders.

This explains a firm’s tendency to restrain itself from maximizing the use of debt.

Debt capacity indicates the maximum proportion of debt the firm can include in its capital structure and still maintain its lowest composite cost of capital (see Figure 12-7).

Слайд 159

Managerial Implications

Determining the firm’s financing mix is critically

important for the manager.

The decision to maximize the market

value of leveraged firm is influenced primarily by the present value of tax shield benefits, present value of bankruptcy costs, and present value of agency costs.

Слайд 160

Dividends

Dividends are distribution from the firm’s assets to

the shareholders.

Firms are not obligated to pay dividends

or maintain a consistent policy with regard to dividends.Dividends could be paid in: cash or stocks

Слайд 161

Dividend Policy

A firm’s dividend policy includes two components:

Dividend

Payout ratio

Indicates amount of dividend paid relative to the

company’s earnings.Example: If dividend per share is $1 and earnings per share is $4, the payout ratio is 25% (1/4)

Stability of dividends over time

Trade-Offs:

If management has decided how much to invest and has chosen the debt-equity mix, decision to pay a large dividend means retaining less of the firm’s profits. This means the firm will have to rely more on external equity financing.

Similarly, a smaller dividend payment will lead to less reliance on external financing.

Слайд 163

DOES DIVIDEND POLICY MATTER TO STOCKHOLDERS?

There are three

basic views with regard to the impact of dividend

policy on share prices:Dividend policy is irrelevant

High dividends will increase share prices

Low dividends will increase share prices

Слайд 164

View #1

Dividend policy is irrelevant

Irrelevance implies shareholder

wealth is not affected by dividend policy (whether the

firm pays 0% or 100% of its earnings as dividends).This view is based on two assumptions: (a) Perfect capital markets; and (b) Firm’s investment and borrowing decisions have been made and will not be altered by dividend payment.

Слайд 165

View #2

High dividends increase stock value

This position in

based on “bird-in-the-hand theory,” which argues that investors may

prefer “dividend today” as it is less risky compared to “uncertain future capital gains.”This implies a higher required rate for discounting a dollar of capital gain than a dollar of dividends.

Слайд 166

View #3

Low dividend increases stock values

In 2003,

the tax rates on capital gains and dividends were

made equal to 15 percent.However, current dividends are taxed immediately while the tax on capital gains can be deferred until the stock is actually sold. Thus, using present value of money, capital gains have definite financial advantage for shareholders.

Thus stocks that allow tax deferral (i.e., low dividends and high capital gains) will possibly sell at a premium relative to stocks that require current taxation (i.e., high dividends and low capital gains).

Слайд 167

Some Other Explanations

The Residual Dividend Theory

Clientele Effect

The Information

Effect

Agency Costs

The Expectations Theory

Слайд 168

Residual Dividend Theory

Determine the optimal capital budget

Determine the

amount of equity needed for financing

First, use retained earnings

to supply this equityIf retained earnings still available, distribute the residual as dividends.

Dividend Policy will be influenced by: (a) investment opportunities or capital budgeting needs, and (b) availability of internally generated capital.

Слайд 169

The Clientele Effect

Different groups of investors have varying

preferences towards dividends.

For example, some investors may prefer a

fixed income stream so would prefer firms with high dividends while some investors, such as wealthy investors, would prefer to defer taxes and will be drawn to firms that have low dividend payout. Thus there will be a clientele effect.

Слайд 170

The Information Effect

Evidence shows that large, unexpected change

in dividends can have a significant impact on the

stock prices.A firm’s dividend policy may be seen as a signal about firm’s financial condition. Thus, high dividend could signal expectations of high earnings in the future and vice versa.

Слайд 171

Agency Costs

Dividend policy may be perceived as a

tool to minimize agency costs.

Dividend payment may require managers

to issue stock to finance new investments. New investors will be attracted only if they are convinced that the capital will be used profitably. Thus, payment of dividends indirectly monitors management’s investment activities and helps reduce agency costs, and may enhance the value of the firm.

Слайд 172

The Expectations Theory

Expectation theory suggests that the market

reaction does not only reflect response to the firms

actions, it also indicates investors’ expectations about the ultimate decision to be made by management.Thus if the amount of dividend paid is equal to the dividend expected by shareholders, the market price of stock will remain unchanged. However, market will react if dividend payment is not consistent with shareholders expectations.

Thus deviation from expectations is more important than actual dividend payment.

Слайд 173

Conclusions on Dividend Policy

Here are some conclusions about

the relevance of dividend policy:

As a firm’s investment opportunities

increase, its dividend payout ratio should decrease.Investors use the dividend payment as a source of information of expected earnings.

Relationship between stock prices and dividends may exist due to implications of dividends for taxes and agency costs.

Based on expectations theory, firms should avoid surprising investors with regard to dividend policy.

The firm’s dividend policy should effectively be treated as a long-term residual.

Слайд 174

The Dividend Decision in Practice

Legal Restrictions

Statutory restrictions may

prevent a company from paying dividends.

Debt and preferred stock

contracts may impose constraints on dividend policy.Liquidity Constraints

A firm may show large amount of retained earnings but it must have cash to pay dividends.

Earnings Predictability

A firms with stable and predictable earnings is more likely to pay larger dividends.

Maintaining Ownership Control

Ownership of common stock gives voting rights. If existing stockholders are unable to participate in a new offering, control of current stockholders is diluted and issuing new stock will be considered unattractive.

Слайд 175 The Dividend Decision in Practice - Alternative Dividend

Policies

Constant dividend payout ratio

The percentage of earnings paid

out in dividends is held constant.Since earnings are not constant, the dollar amount of dividend will vary every year.

Stable dollar dividend per share

This policy maintains a relatively constant dollar of dividend every year.

Management will increase the dollar amount only if they are convinced that such increase can be maintained.

Слайд 176 The Dividend Decision in Practice - Alternative Dividend

Policies

A small regular dividend plus a year-end extra

The company

follows the policy of paying a small, regular dividend plus a year-end extra dividend in prosperous years.

Слайд 177

Dividend Payment Procedures

Generally, companies pay dividend on a

quarterly basis. The final approval of a dividend payment

comes from the firm’s board of directors.For example, on February 6, 2009, GE announced that it would pay quarterly dividend of $0.31 each to its shareholders for 2009. The annual dividend would be $0.31*4 = $1.24 per share.

Слайд 178

Important Dates

Declaration date – The date when the

dividend is formally declared by the board of directors (for

example, February 6)Date of record – Investors shown to own stocks on this date receive the dividend (February 23)

Ex-dividend date – Two working days prior to date of record (for example, February 19, since Feb. 23 was a Monday). Shareholders buying stock on or after ex-dividend date will not receive dividends.

Payment date – The date when dividend checks are mailed (for example, April 27)

Слайд 179

Stock Dividends

A stock dividend entails the distribution of

additional shares of stock in lieu of cash payment.

While

the number of common stock outstanding increases, the firm’s investments and future earnings prospects do not change.

Слайд 180

Stock Splits

A stock split involves exchanging more (or

less in the case of “reverse” split) shares of

stock for firm’s outstanding shares.While the number of common stock outstanding increases (or decreases in the case of reverse split), the firm’s investments and future earnings prospects do not change.

Stock splits and stock dividends are far less frequent than cash dividends.

Слайд 181

Stock Repurchases

A stock repurchase (stock buyback) occurs when

a firm repurchases its own stock. This results in

a reduction in the number of shares outstanding.From shareholder’s perspective, a stock repurchase has potential tax advantage as opposed to cash dividends.

Слайд 182

Stock Repurchase -- Benefits

A means of providing an

internal investment opportunity

An approach for modifying the firm’s capital

structureA favorable impact on earnings per share

The elimination of a minority ownership group of stockholders

The minimization of the dilution in earnings per share associated with mergers

The reduction in the firm’s costs associated with servicing small stockholders

Слайд 183 A Share Repurchase as a Dividend, Financing, Investment

Decision

When a firm repurchases stock when it has excess

cash, it can be regarded as a dividend decision.If a firm issues debt and then repurchases stock, it alters the debt-equity mix and thus can be regarded as a financing or capital structure decision.

If a firm repurchases stock because it feels the prices are depressed, the decision to repurchase may be seen as an investment decision. Of course, no company can survive or prosper by investing only its own stock!

Слайд 184

Unsecured Sources:

Trade Credit

Trade credit arises spontaneously with the

firm’s purchases. Often, the credit terms offered with trade

credit involve a cash discount for early payment.For example, the terms “2/10 net 30” means a 2% discount is offered for payment within 10 days, or the full amount is due in 30 days.

In this case, a 2% penalty is involved for not paying within 10 days.

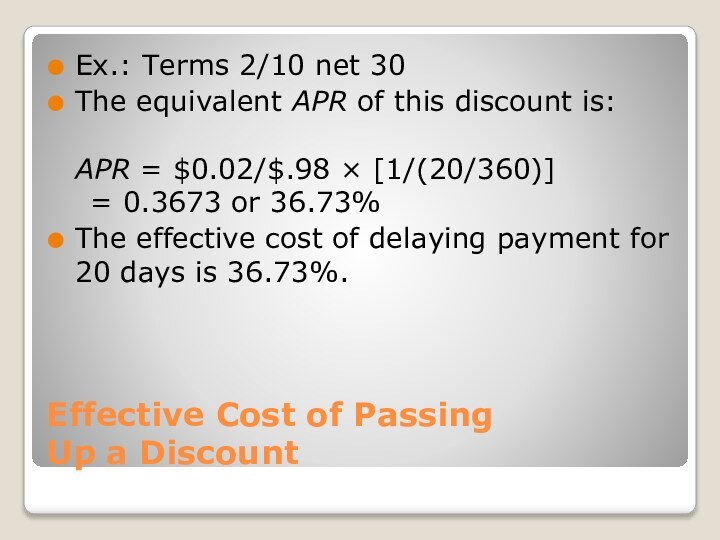

Слайд 186

Effective Cost of Passing

Up a Discount

Ex.: Terms

2/10 net 30

The equivalent APR of this discount is:

APR

= $0.02/$.98 × [1/(20/360)]

= 0.3673 or 36.73%The effective cost of delaying payment for 20 days is 36.73%.

Слайд 187

Unsecured Sources:

Bank Credit

Commercial banks provide unsecured short-term

credit in two forms:

Lines of credit

Transaction loans (notes payable)

Слайд 188

Line of Credit

Informal agreement between a borrower and

a bank about the maximum amount of credit the

bank will provide the borrower at any one time.There is no legal commitment on the part of the bank to provide the stated credit.

Banks usually require that the borrower maintain a minimum balance in the bank throughout the loan period (known as compensating balance).

Interest rate on a line of credit tends to be floating.

Слайд 189

Revolving Credit

Revolving credit is a variant of the

line of credit form of financing.

A legal obligation is

involved.

Слайд 190

Transaction Loans

A transaction loan is made for a

specific purpose. This is the type of loan that

most individuals associate with bank credit and is obtained by signing a promissory note.

Слайд 191

Unsecured Sources:

Commercial Paper

The largest and most credit-worthy

companies are able to use commercial paper—a short-term promise

to pay that is sold in the market for short-term debt securities.Maturity: Usually 6 months or less.

Interest Rate: Slightly lower (1/2 to 1%) than the prime rate on commercial loans.

New issues of commercial paper are placed directly or dealer placed.

Слайд 192

Commercial Paper: Advantages

Interest rates

Rates are generally lower than

rates on bank loans

Compensating-balance requirement

No minimum balance requirements are

associated with commercial paperAmount of credit

Offers the firm with very large credit needs a single source for all its short-term financing

Prestige

Signifies credit status

Слайд 193

Secured Sources of Loans

Secured loans have assets of

the firm pledged as collateral. If there is a

default, the lender has first claim to the pledged assets. Because of its liquidity, accounts receivable is regarded as the prime source for collateral.Accounts Receivable Loans

Pledging Accounts Receivable

Factoring Accounts Receivable

Inventory Loans

Слайд 194

Pledging Accounts Receivable

Borrower pledges accounts receivable as collateral

for a loan obtained from either a commercial bank

or a finance company.The amount of the loan is stated as a percentage of the face value of the receivables pledged.

If the firm pledges a general line, then all of the accounts are pledged as security (simple and inexpensive).

If the firm pledges specific invoices, each invoice must be evaluated for creditworthiness (more expensive).

Слайд 195

Pledging Accounts Receivable

Credit Terms: Interest rate is 2–5%

higher than the bank’s prime rate. In addition, handling

fee of 1–2% of the face value of receivables is charged.While pledging has the attraction of offering considerable flexibility to the borrower and providing financing on a continuous basis, the cost of using pledging as a source of short-term financing is relatively higher compared to other sources.

Слайд 196

Pledging Accounts Receivable

Factoring accounts receivable involves the outright

sale of a firm’s accounts to a financial institution

called a factor.A factor is a firm (such as commercial financing firm or a commercial bank) that acquires the receivables of other firms. The factor bears the risk of collection in exchange for a fee of 1–3 percent of the value of all receivables factored.

Слайд 197

Secured Sources:

Inventory Loans

These are loans secured by

inventories.

The amount of the loan that can be obtained

depends on the marketability and perishability of the inventory.

Слайд 198

Types of Inventory Loans

Floating or Blanket Lien Agreement

The

borrower gives the lender a lien against all its

inventories.Chattel Mortgage Agreement

The inventory is identified and the borrower retains title to the inventory but cannot sell the items without the lender’s consent.

Field Warehouse-Financing Agreement

Inventories used as collateral are physically separated from the firm’s other inventories and are placed under the control of a third-party field-warehousing firm.

Terminal Warehouse Agreement

Inventories pledged as collateral are transported to a public warehouse that is physically removed from the borrower’s premises.

Слайд 199

Working Capital

Working capital - The firm’s total investment

in current assets.

Net working capital - The difference between

the firm’s current assets and its current liabilities.

Слайд 200

Managing Net Working Capital

Managing net working capital is

concerned with managing the firm’s liquidity. This entails managing

two related aspects of the firm’s operations:Investment in current assets

Use of short-term or current liabilities

Слайд 201

How Much Short-Term Financing Should a Firm Use?

This

question is addressed by hedging principle of working-capital management

Слайд 202

The Appropriate Level of Working Capital

Managing working capital

involves interrelated decisions regarding investments in current assets and

use of current liabilities.Hedging principle or principle of self-liquidating debt provides a guide to the maintenance of appropriate level of liquidity.

Слайд 203

The Hedging Principle

The hedging principle involves matching the

cash-flow-generating characteristics of an asset with the maturity of

the source of financing used to finance its acquisition.Thus, a seasonal need for inventories should be financed with a short-term loan or current liability.

On the other hand, investment in equipment that is expected to last for a long time should be financed with long-term debt.

Слайд 205

Permanent and Temporary Assets

Permanent investments

Investments that the

firm expects to hold for a period longer than

one yearTemporary investments

Current assets that will be liquidated and not replaced within the current year

Слайд 206

Temporary and Permanent Sources of Financing

Temporary sources of

financing consist of current liabilities such as short-term secured

and unsecured notes payable.Permanent sources of financing include intermediate-term loans, long-term debt, preferred stock, and common equity.

Слайд 208

The Cash Conversion Cycle

A firm can minimize its

working capital by speeding up collection on sales, increasing

inventory turns, and slowing down the disbursement of cash. This is captured by the cash conversion cycle (CCC).CCC = days of sales outstanding + days of sales in inventory – days of payables outstanding.

Figure 15-2 shows that both Dell and Apple have been effective in reducing their CCC.

CCC is below zero due to effective management of inventories and being able to receive favorable credit terms.

See Table 15-2 for Dell’s CCC.

Слайд 212

APR example

A company plans to borrow $1,000 for

90 days. At maturity, the company will repay the

$1,000 principal amount plus $30 interest. What is the APR? APR = ($30/$1,000) × [1/(90/360)] = 0.03 × (360/90) = 0.12 or 12%

Слайд 213

Annual Percentage Yield (APY)

APR does not consider compound

interest. To account for the influence of compounding, we

must calculate APY or annual percentage yield.APY = (1 + i/m)m – 1

Where:

i is the nominal rate of interest per year

m is number of compounding periods within a year