Слайд 2

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE A. Socrates (469

BC–399 BC)

Socrates (469 BC–399 BC)

Credited as one

of the founders of Western philosophy.

Known only through the classical accounts of his students.

Plato's dialogues are the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity.

Socrates who also lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method.

Слайд 3

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE A. Socrates

Socrates

He agreed

with sophists.

Personal experience is important, but denied that no

truth exists beyond personal opinion.

Method of inductive definition

Examine instances of a concept

Ask the question – what is it that all instances have in common?

Find the essence of the instances of the concept.

Seek to find general concepts by examining isolated instances.

Слайд 4

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE A. Socrates

Socrates

The essence

was a universally accepted definition of a concept.

Understanding essences

constituted knowledge and goal of life was to gain knowledge.

Socrates was sentenced to death at the age of 70 years for corrupting the youth of Athens

Слайд 5

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

Plato (428

– 348 BCE)

He was a classical Greek philosopher

and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the western world.

Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy.

Plato was originally a student of Socrates, and was as influenced by his thinking and unjust death.

Слайд 6

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

Theory of

forms

Everything in the empirical world is an inferior manifestation

of the pure form, which exists in the abstract.

Experience through our senses comes from interaction of the pure form and matter of the world

Result is an experience less than perfect.

True knowledge can be attained only through reason; rational thought regarding the forms.

Слайд 7

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The analogy

of the divided line

Description of Plato’s view of

acquisition of true knowledge.

The analogy divides the world and our states of mind into points along a divided line.

An attempt to gain knowledge through sensory experience is doomed to ignorance or opinion.

Imagining is lowest form of understanding

Direct experience with objects is slightly better, but still just beliefs or opinions.

Слайд 8

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The analogy

of the divided line

Contemplation of mathematical relationships is

better than imagination and direct experience.

Highest form of thinking involves embracing the forms.

True knowledge and intelligence comes only from understanding the abstract forms.

The allegory of the cave

Demonstrates how difficult it is to deliver humans from ignorance

Слайд 9

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The reminiscence

theory of knowledge

How do we know the forms

if we cannot know them through sensory experiences?

Prior to coming into the body, the soul dwelt in pure, complete knowledge.

Knowledge is innate and attained only through introspection

Thus, all true knowledge comes only from remembering the experiences the soul had prior to entering the body.

Слайд 10

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The reminiscence

theory of knowledge

The reminiscence theory of knowledge made

Plato a rationalist who stressed mental operations to gain knowledge already in the soul.

Слайд 11

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The nature

of the soul

Soul comprised of three parts (tripartite)

Rational

component

immortal, existed with the forms.

Courageous (emotional or spirited) component

mortal emotions such as fear, rage, and love

Appetite component

mortal needs such as hunger, thirst, and sexual behavior that must be satisfied

Слайд 12

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The nature

of the soul

To obtain knowledge, one must suppress bodily

needs and concentrate on rational pursuits.

Job of rational component is to postpone and inhibit immediate gratification when it is in the best long-term benefit of the person.

Слайд 13

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

The Republic

Plato

described a utopian society with three types of people

performing specific functions:

appetitive individuals – workers and slaves.

courageous individuals – soldiers.

rational individuals – philosopher-kings.

Слайд 14

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

Plato felt

that all was predetermined.

A complete nativist, people are destined

to be a slave, soldier, or philosopher-king.

While asleep, the baser appetites in people are fulfilled no matter how rational they are while awake

Plato is referring to dreams although he does not mention them specifically.

Слайд 15

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE B. Plato

Plato’s legacy

Because

of his disdain for empirical observation and sensory experience

as means of gaining knowledge, he actually inhibited progress in science.

Dualism in humans

Слайд 16

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle (384

BC – 322 BC)

A student of Plato and

teacher of Alexander the Great.

He was the first to create a comprehensive system of Western philosophy, encompassing morality and aesthetics, logic and science, politics and metaphysics.

Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues, but only about one-third of the original works have survived.

Слайд 17

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle’s Legacy

Physical sciences

profoundly shaped medieval scholarship, and its influence

extended well into the Renaissance, although ultimately replaced by Newtonian Physics.

Biological sciences,

Some observations were confirmed to be accurate only in the 19 C.

Logic

His work was incorporated into modern formal logic.

Слайд 18

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle’s Legacy

Metaphysics

He had a profound influence on philosophical and theological

thinking in the Islamic and Jewish traditions in the Middle Ages.

It continues to influence Christian theology, especially Eastern Orthodox theology, and the scholastic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church.

All aspects of Aristotle's views continue to be the object of active academic study today.

Слайд 19

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle and

Plato contrasted.

Plato:

Essences (truths) in the forms that exist

independent of nature, known only by using introspection (rationalism)

Aristotle

Essences could be known only by studying nature through individual observation of phenomena (empiricism).

Aristotle a rationalist and empiricist.

Mind employed to gain knowledge (rationalist), object of the rational thought was information from sensory experience (empiricism).

Слайд 20

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle’s Lyceum

Located just outside the walls of ancient Athens

Before starting

the Lyceum, Aristotle had studied for 19 years (366-347 BC) at Plato's Academy.

Head of his school until 323 BC

Athenians turned against the Alexandrian Empire upon Alexander the Great’s death (his student 343- 335 BCE)

He left Athens fearing for his life, saying famously that "Athens must not be allowed to sin twice against philosophy."

The school was sacked by Romans general

The location of the complex was lost for centuries, until it was rediscovered in 1996, during excavations which revealed foundations and few other remains.

Слайд 21

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle’s four

causes

Aristotle’s four causes, to understand object or phenomenon, one

must know causes.

Material cause

matter of which it is made

Formal cause

form or pattern of the object – what is it?

Efficient cause

force that transforms the matter – who made it?

Final cause

purpose – why it exists.

Слайд 22

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Aristotle’s causation,

teleology, and entelechy

Everything has a cause and purpose

Teleology, meaning

that everything has a function (entelechy) built into it.

Entelechy keeps an object moving and developing in its prescribed direction to full potential

Scala naturae is the idea that nature is arranged in a hierarchy ranging from neutral matter to the unmoved mover, which is the cause of everything in nature

Слайд 23

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Hierarchy of

souls: What gives life:

Vegetative (nutritive) soul

Provides growth, assimilation

of food, and reproduction

Possessed by plants

Sensitive soul

Functions of vegetative soul plus the ability to sense and respond to the environment, experience pleasure and pain, and use memory.

Possessed by animals.

Слайд 24

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Hierarchy of

souls:

Rational soul

Vegetative and sensitive souls plus ability for thinking

and rational thought.

Possessed by humans.

Sensation

From the five senses

Perception was explained by motion of objects that stimulate a particular sensory system.

We can trust our senses to yield an accurate representation of the real world environment

Слайд 25

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Common sense,

passive and active reason.

Sensory information is only first step

in gaining knowledge – necessary but not sufficient element in obtaining knowledge.

Information from multiple sensory systems must be combined for effective interactions with the environment.

Common sense

Coordinates and synthesizes information from all of the senses for more meaningful and effective experience.

Слайд 26

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Common sense,

passive and active reason.

Passive reason

Uses synthesized experience to function

in everyday life

Active reason

Uses synthesized experience to abstract principles and essences

Highest form of thinking

Active reason provides humans with their entelechy

Purpose is to engage in active reason

Source of greatest pleasure.

Слайд 27

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Unmoved Mover

Gave

everything in nature its purpose (entelechy)

Caused everything in

nature, but was not caused by anything itself

It set nature in motion and little else

It was a logical necessity, not a god

Слайд 28

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Memory and

recall

Remembering

Spontaneous recollection of a previous experience

Recall

An actual

mental search for a previous experience

Practice of recall affected by laws of association

Law of contiguity

Associate things that occurred close in time and/or in same situations

Слайд 29

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Law of

similarity

Similar things are associated

Law of contrast

Opposite things

are associated

Law of frequency

More often events occur together – stronger the association

Associationism

Belief that associations can be used to explain origins of ideas, memory, or how complex ideas are formed from simple ones

Laws of association are basis for most theories of learning and association.

Слайд 30

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Imagination and

dreaming

Imagination is the lingering effects of sensory experience.

Dreams are

images from past experiences which are stimulated by events inside and outside the body

Motivation and happiness

Happiness is doing what is natural

Fulfills one’s purpose

Purpose for humans is to think rationally

Humans are motivated by appetites but can use rational powers to inhibit them.

Слайд 31

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE C. Aristotle

Motivation and

happiness

Conflicts arise between immediate satisfaction and biological drives and

more remote rational goals.

Like most Greeks, Aristotle held self-control and moderation as a high ideal.

The best life lived according to golden mean (between excess and deficiency).

Emotions and selective perception

Emotions function to amplify any existing tendency (behavior).

Influences perception to be selective.

Слайд 32

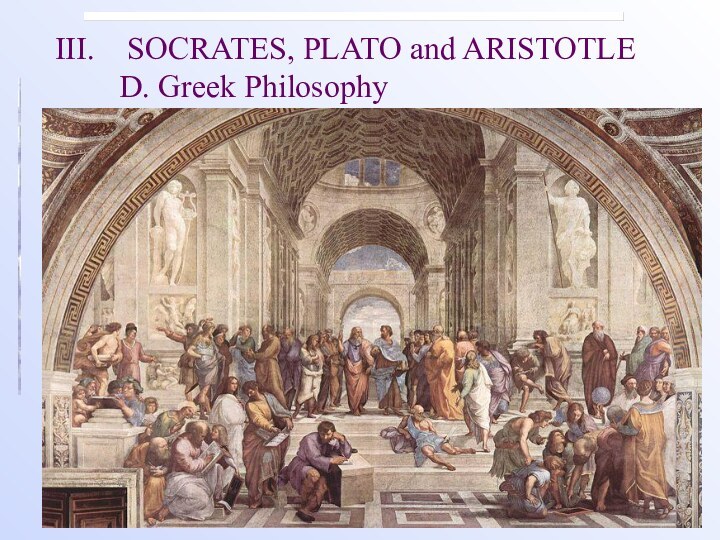

III. SOCRATES, PLATO and ARISTOTLE D. Greek Philosophy

Greek

Philosophical Tradition

The Greek cosmologists broke loose from the accepted

traditions and speculated; they also engaged in critical discussion.

After Aristotle’s death, philosophers either relied on teachings of past authorities, particularly Aristotle, or turned attention from descriptions of the universe to models of human conduct.

The critical, questioning tradition of the Greeks was not present until revived in the Renaissance.