- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему Variants of the English Language

Содержание

- 2. 1. The Main Variants of the English

- 3. For historical and economic reasons the English

- 4. Standard Englishmay be defined as that form

- 5. Variants of English are regional variants possessing

- 6. 2. Variants of English in the United

- 7. Lexical peculiarities of Scottish English Some semantic

- 8. Some words used in Scottish English have

- 9. Many words which have the same form,

- 10. Irish Englishsubsumes all the Englishes of the

- 11. The Irish English vocabulary is characterized by:

- 12. the use of most regionally marked words

- 13. the Gaelic influence on meanings of some

- 14. the layer of words shared with Scottish

- 15. Variants of English outside the British Isles:American

- 16. American English is the variety of the

- 17. a) Historical Americanisms: fall – ‘autumn’; to

- 18. b) Proper Americanisms were not discovered in

- 19. c) Specifically American borrowings reflect the historical

- 20. d) American shortenings: dorm – dormitory; mo – moment; cert – certainly.

- 21. Canadian English is the variety of the

- 22. Australian English is similar to British English,

- 23. Australian English has a unique set of

- 24. New Zealand English is the variety of

- 25. Many local words in New Zealand English

- 26. New Zealand idiomsIt is in idioms, in

- 27. South African English is the variety of

- 28. In South African English there are words

- 29. Indian English is the variety of the

- 30. Despite the fact that British English

- 31. Phonetic peculiarities of Indian English, rhotic [r]

- 32. Some Peculiarities of British English and American

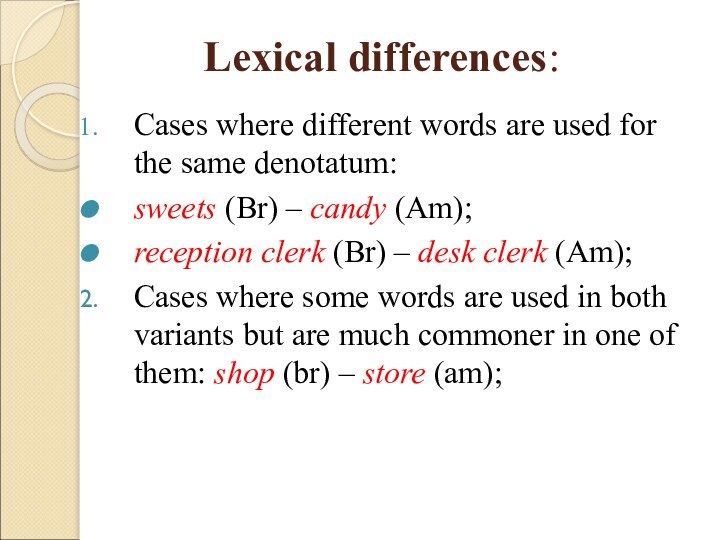

- 34. Lexical differences: Cases where different words are

- 35. Cases where one (or more) lexico-semantic variant(s)

- 36. Cases where there are no equivalent words

- 37. 3) Derivational and morphological peculiarities: Such affixes as

- 38. Am.E. sometimes favours words that are morphologically

- 39. Social Variation of the English LanguageSocial language

- 40. The language is the chief signal of

- 41. Gender IssuesSexism – discrimination against one sex,

- 42. In vocabulary, attention has been focused on

- 43. Gender issues have gained a serious scientific

- 44. Critical discourse analysisIs the approaches to the

- 45. Cultural practice theoryThe second approach centers its

- 46. Lingua Genderrologyis an independent branch in linguistic

- 47. Occupational varietiesThe term occupational dialect is associated

- 48. Religious English is a variety in which

- 49. Legal English Is in common with Religious

- 50. Legal English has several subvarietiesthe language of

- 51. News Media Englishis a variety that includes

- 52. Distinctive features of news reporting:The headline is

- 53. Advertising Englishcan be observed in commercial advertising.

- 54. Lexically, this variety of English tends to

- 55. English is now the dominant or official

- 56. Скачать презентацию

- 57. Похожие презентации

1. The Main Variants of the English LanguageEvery language allows different kinds of variations: geographical;territorial;stylistic and others.

![Variants of the English Language Phonetic peculiarities of Indian English, rhotic [r] is pronounced in all positions;](/img/tmb/15/1480265/c747654a850c29401e216241abab3429-720x.jpg)

Слайд 2

1. The Main Variants of the English Language

Every

language allows different kinds of variations:

Слайд 3 For historical and economic reasons the English language

has spread over vast territories. It is the national

language of:England proper,

the USA,

Australia,

New Zealand,

some provinces of Canada.

It is the official language in:

Wales,

Scotland,

in Gibraltar,

on the island of Malta.

Слайд 4

Standard English

may be defined as that form of

English which is current and literary, substantially uniform and

recognized as acceptable wherever English is spoken or understood. Standard English is the variety most widely accepted and understood either within an English-speaking country or throughout the entire English-speaking world.

Слайд 5

Variants of English

are regional variants possessing a

literary norm. There are distinguished variants existing on the

territory of the United Kingdom:British English,

Scottish English,

Irish English,

Variants existing outside the British Isles:

American English,

Canadian English,

New Zealand English,

South African English,

Indian English.

British English is referred to the written Standard English and the pronunciation known as Received Pronunciation (RP).

Слайд 6

2. Variants of English in the United Kingdom

Scottish

English has a long tradition as a separate written

and spoken variety. Pronunciation, grammar and lexis differ from other varieties of English existing on the territory of the British Isles. It can be explained by its historical development.The identity of Scottish English reflects an institutionalized social structure, as it is most noticeable in the realm of law, local government, religion, and education.

Слайд 7

Lexical peculiarities of Scottish English

Some semantic fields

are structured differently in Scottish English and in British

English, e.g. the term minor in British English is used to denote a person below the age of 18 years, while Scottish law distinguishes between pupils (to age 12 for girls and 14 for boys) and minors (older children up to 18);Слайд 8 Some words used in Scottish English have equivalents

in British English, e.g. (ScE) extortion – (BrE) blackmail;

The distinctiveness of Scottish English derived from the influence of other languages, especially Gaelic, Norwegian, and French., e.g., Gaelic borrowings include:

cairn – ‘a pile of stones that marks the top of a mountain or some other special place’;

sporran – ‘a small furry bag that hangs in front of a man’s kilt as part of traditional Scottish dress’

Слайд 9 Many words which have the same form, but

different meanings in Scottish English and British English, e.g.

the word gate in Scottish English means ‘road’;Some Scottish words and expressions are used and understood across virtually the whole country, e.g.

dinnae (don’t),

wee (‘small’),

kirk (‘church’),

lassie (‘girl’).

Слайд 10

Irish English

subsumes all the Englishes of the Ireland.

The two main politico-linguistic divisions are Southern and Northern,

within and across which further varieties are Anglo-Irish, Hiberno-English [haɪ'bɜːnəu-], Ulster Scots, and the usage of the two capitals, Dublin and Belfast.

Слайд 11

The Irish English vocabulary is characterized by:

the

presence of words with the same form as in

British English but different meanings in Irish English, e.g.backward – ‘shy’;

to doubt – ‘to believe strongly’;

bold – ‘naughty’;

Слайд 12 the use of most regionally marked words by

older, often rural people, e.g.

biddable ‘obedient’; покорный

feasant –

‘affable’; приветливыйthe presence of nouns taken from Irish which often relate either to food or the supernatural, e.g. banshee – ‘fairy woman’ from bean sidhe;

Слайд 13 the Gaelic influence on meanings of some words,

e.g. to destroy and drenched. These words have the

semantic ranges of their Gaelic equivalents mill ‘to injure, spoil’ and báite ‘drenched, drowned, very wet’;the presence of words typical only of Irish English (the so-called Irishisms), e.g. begorrah – ‘by God’;

Слайд 14 the layer of words shared with Scottish English,

e.g.:

ava – ‘at all’;

greet – ‘cry, weep’;

brae

– ‘hill, steep slope’. Besides distinctive features in lexis Irish English has grammatical, phonetical and spelling peculiarities of its own, e.g.:

the use of ‘does be/ do be’ construction in the following phrase: ‘They do be talking on their mobiles a lot’;

the plural form of you is distinguished from the singular, normally by using the otherwise archaic English word ye to denote plurality, e.g. ‘Did ye all go to see it?’

Слайд 15

Variants of English outside the British Isles:

American English,

Canadian English,

Australian English,

New Zealand English,

South African

English, Indian English, etc.

Слайд 16

American English

is the variety of the English

language spoken in the USA. The first wave of

English-speaking immigrants was settled in North America in the 17th century. There were also people who spoke Dutch, French, German, Spanish, Swedish, and Finnish languages.Whole groups of words which belong to American vocabulary exclusively and constitute its specific features are called Americanisms.

Слайд 17

a) Historical Americanisms:

fall – ‘autumn’;

to guess

– ‘to think’;

sick – ‘ill, unwell’.

In American

usage these words still retain their old meanings whereas in British English their meanings have changed or fell out of use.

Слайд 18

b) Proper Americanisms

were not discovered in British

vocabulary: redbud багряник– ‘an American tree having small budlike

pink flowers’;blue-grass – ‘a sort of grass peculiar to North America’.

Слайд 19

c) Specifically American borrowings

reflect the historical contacts

of the Americans with other nations on the American

continent:ranch, sombrero (Spanish borrowings),

Toboggan, caribou канадский олень (Indian borrowings).

Слайд 21

Canadian English

is the variety of the English

language used in Canada and close to American English.

Specifically Canadian words are called Canadianisms, e.g.:parkade – ‘parking garage’;

chesterfield – ‘a sofa, couch’;

to fathom out – ‘to explain’,

to table a document – ‘to present it’, whereas in American English it means ‘to withdraw it from consideration’.

Слайд 22

Australian English

is similar to British English, but

also borrows from American English, e.g. truck is used

instead of lorry. The exposure to the different spellings of British and American English leads to a certain amount of spelling confusion, e.g. behaviour as opposed to behavior.Uniquely Australian terms:

outback – remote regional areas;

walkabout – a long journey of certain length;

bush – native forested areas.

Слайд 23 Australian English has a unique set of diminutives

formed by adding –o or –ie to the ends

of words:arvo (afternoon),

servo (service station),

barbie (barbecue),

bikkie (biscuit).

A very common feature of traditional Australian English is rhyming slang based on Cockney rhyming slang and imported by migrants from London in the 19th century, e.g.:

Captain Cook rhymes with look, so to have a captain cook, or to have a captain, means to have a look.

Слайд 24

New Zealand English

is the variety of the

English language spoken in New Zealand and close to

Australian English in pronunciation.The only deference between New Zealand and British spelling is in the ending –ise or –ize.

New Zealanders use the –ise ending exclusively, whereas Britons use either ending, and some British dictionaries prefer the –ize ending.

Слайд 25 Many local words in New Zealand English were

borrowed from the ‘Maori population to describe the local

flora, fauna, and the natural environment, e.g.the names of birds (kiwi, tui );

the names of fish (shellfish,, hoki);

the names of native trees (kauri, rimu) and many others.

Words that are unique to New Zealand English or shared with Australian English, e.g.

bach – ‘a small holiday home, often with only one or two rooms and of simple construction’;

footpath – ‘pavement’;

togs – ‘swimming costume’.

Слайд 26

New Zealand idioms

It is in idioms, in different

metaphoric phrases that New Zealand English has made most

progress or divergence. Often they reflect significant differences in culture., e.g.:up the Puhoi without a paddle –‘to be in difficulties without an obvious solution’;

sticky beak – ‘someone unduly curious about people’s affairs’.

The latter idiom in Australia is quite pejorative whereas in New Zealand it is used with more affection and usually as a tease.

Слайд 27

South African English

is the variety of the

English language used in South Africa and surrounding counties

(Namibia, Zimbabwe). It is a mother tongue only for 40 % of the white inhabitants and a tiny minority of black inhabitants of the region. South African English bears some resemblance in pronunciation to a mix of Australian and British English.Слайд 28 In South African English there are words that

do not exist in British and American English, usually

derived from African languages, e.g.bra, bru – ‘male friend’,

dorp – ‘a small rural town or village’,

sat – ‘dead, passed away’.

In South African English:

boy – ‘a black man’ (derogative),

township – ‘urban area for black, coloured or Indian South Africans under apartheid’, расовая изоляция

book of life – ‘national identity document’.

Слайд 29

Indian English

is the variety of the English

language spoken in India. The language that Indians are

taught in schools is essentially British English and in particular, spellings follow British conventions. Many phrases that the British may consider antique are still popular in India.Official letters include phrases like

please do the needful,

you will be intimated shortly,

your obedient servant.

Indian English mixes in various words from Indian languages, e.g. bandh or hartal for strikes, challen for a monetary receipt or a traffic ticket.

Слайд 30 Despite the fact that British English is

an official language of Government in India, there are

words used only in Indian English are:crore – ‘ten millions’;

scheduled tribe – ‘a socially/economically backward Indian tribe, given special privileges by the government’,

mohalla – ‘an area of a town or village, a community’.

Слайд 31

Phonetic peculiarities of Indian English,

rhotic [r] is

pronounced in all positions;

the distinction between [v] and

[w] is generally neutralized to [w];in such words as old and low the vowel is generally [ɔ], etc.

A variety in syntax:

one used rather than the indefinite article: He gave me one book, yes;

no as question tags: He is coming, yes?

Present Perfect rather than Past Simple:

I have bought the book yesterday, etc.

Слайд 32

Some Peculiarities of British English and American English

The

American variant of the English language differs from British

English in pronunciation, some minor features of grammar, spelling standards and vocabulary.The American spelling is in some respects simpler than its British counterpart, in other respects just different.

Слайд 34

Lexical differences:

Cases where different words are used

for the same denotatum:

sweets (Br) – candy (Am);

reception

clerk (Br) – desk clerk (Am); Cases where some words are used in both variants but are much commoner in one of them: shop (br) – store (am);

Слайд 35 Cases where one (or more) lexico-semantic variant(s) is

(are) specific to either British or American English. Both

variants of English have the word faculty. But only in Am. E. it denotes ‘all the teachers and other professional workers of a university or college’. In Br.E. it means ‘teaching staff’.Cases where the same words have different semantic structure in Br. And Am. E.: homely in Br.E. means ‘home-loving’ in Am.E. “unattractive in appearance’.

Слайд 36 Cases where there are no equivalent words in

one of the variants, e.g. drive-in in Am.E. denotes

‘a cinema or restaurant that one can visit without leaving one’s car’.Cases where the connotational aspect of meaning comes to the fore. The word politician in Br.E. means ‘a person who is professionally involved in politics’, whereas in Am.E. the word is derogatory as it means ‘a person who acts in a manipulative way, typically to gain advancement within an organization’.

Слайд 37

3) Derivational and morphological peculiarities:

Such affixes as –ee,

-ster, -super are more frequent in Am.E.:

draftee –

‘a young man about to be enlisted”, roadster – ‘motor-car for long journeys by road’,

super-market – ‘a very large shop that sells food and other products for the home’.

Слайд 38 Am.E. sometimes favours words that are morphologically more

complex: transportation – transport (br). In some cases the

formation of words by means of affixes is more preferable in Am.E. while the in Br.E. the form is back-formation: burglarize (Am) – burgle (from burglar) (Br).

Слайд 39

Social Variation of the English Language

Social language variation

deals with different identities a person acquires participating in

social structure. Social language variation provides an answer to the question ‘Who are you?’People belong to different social groups and perform different social roles. A person might be identified as ‘a woman’, ‘ parent,’ ‘a doctor’, ‘a political activist’, etc. Any of these identities can have consequences for the kind of language people use.

Слайд 40 The language is the chief signal of both

permanent and transparent aspects of a person’s social identity.

Certain aspects of social variation seem to be particular linguistic consequence. Age, sex, and socioeconomic class have been repeatedly shown to be of importance when it comes to explaining the way sounds, grammatical constructions, and vocabulary vary.

Adopting a social role invariably involves a choice of appropriate linguistic forms.

Слайд 41

Gender Issues

Sexism – discrimination against one sex, typically

men against women. There is now a widespread awareness

of the way in which language displays social attitudes towards men and women. The criticism have been mainly directed at the bases built into English vocabulary and grammar which reflect a traditionally male-oriented view of the world that reinforces the low status of women in society. Thus, gender issues have become part of the problem of political correctness.Слайд 42 In vocabulary, attention has been focused on the

replacement of ‘male’ words with a generic meaning by

neutral items, e.g.:chairman becomes chair or chairperson,

salesman – sales assistant.

In certain cases, such as job descriptions, the use of sexually neutral language has become a legal requirement.

The vocabulary of marital status has also been affected – notably in the introduction of Ms as a neutral alternative to Miss or Mrs.

Слайд 43 Gender issues have gained a serious scientific ground

and development in Britain, the USA and in European

countries.The problem connected with the interaction of language and gender – defined as a sociocultural category – is concerned with answers to the following questions:

Why do gender ideologies appear?

Why are particular gender notions practiced through language?

How are gender ideologies constituted / constructed in language?, and

In what way do they shape discourse communities?

Слайд 44

Critical discourse analysis

Is the approaches to the investigation

of gender in modern linguistics.

It examines:

the interaction

between language and social structures, how social structures are constituted by linguistic interaction.

It aims:

to provide accounts of the production, internal structure, and overall organization of texts,

to investigate the sociopolitical and cultural presuppositions and implications of discourse.

Слайд 45

Cultural practice theory

The second approach centers its attention

on:

the constitution of cultural meanings,

the significance of individual

experience as a force in this process. The approach examines members’ everyday lived experiences as a whole to demonstrate how they constitute gender ideologies.

It reveals:

the categories ‘men’ and ‘women’ by examining what people do to shape these cultural categories,

how individuals form cultural meanings and use them on the basis of their own gender practices and everyday activities.

Слайд 46

Lingua Genderrology

is an independent branch in linguistic science

that has given rise to a number of scientifically

well-grounded works in such fields of the English language as phonetics, grammar, lexis, phraseology.In Russia among the most significant investigations based on the material of different languages, works are carried out by the members of the laboratory of Gender Studies of Moscow State Linguistic University.

Слайд 47

Occupational varieties

The term occupational dialect is associated with

a particular way of earning a living.

All occupations

are linguistically distinctive to some degree. The more specialized the occupation, and the more senior or professional the post, the more technical the language is likely to be. Occupational varieties of the English language:

Religious English,

Legal English,

News Media English,

Advertising English.

They provide the clearest cases of differences and peculiarities in phonology, grammar, vocabulary, and patterns of discourse.

Слайд 48

Religious English

is a variety in which all

aspects of structure are implicated:

Phonological identity is in such

genres as spoken prayers, sermons проповедь, chants песнопение, including the unusual case of unison speech. Graphological identity is found in liturgical leaflets, biblical texts, and many other religious publications.

Grammatical identity - in invocations, prayers, blessings, and other ritual forms, both public and private.

Lexical identity pervades formal articles of faith and scriptural texts, with the lexicon of doctrine informing the whole of religious expression.

Distinctive discourse identity - in such domains as liturgical services, preaching, and rites of passage (e.g. wedding, funerals).

Слайд 49

Legal English

Is in common with Religious English

as it shares with religion a respect for ritual

land tradition. When English eventually became the official language of the law in Britain (17th century), a vast amount of earlier vocabulary had already become fixed in legal usage.The reliance on Latin phrasing: mens rea вина

French borrowings: lien – was supplemented by ceremonial phrasing (signed, sealed, and delivered), conventional terminology (alibi, negotiate instrument), and other features which have been handed down to form present-day legal language.

Слайд 50

Legal English has several subvarieties

the language of legal

documents, such as contracts, deeds, insurance policies, wills;

the

language of works of legal reference, with their complex apparatus of footnotes and indexing; the language of case law, made up of the spoken or written decisions which judges make about individual cases.

Слайд 51

News Media English

is a variety that includes newspaper

language, radio language, and television language.

News reports are characterized

by the use of: the so-called ‘preferred’ forms of expressions,

lack of stylistic idiosyncrasy,

their consistence of style over long periods of time.

Слайд 52

Distinctive features of news reporting:

The headline is critical,

summarizing and drawing attention to the story (telegraphic style);

The

first (‘lead’) paragraph both summarizes and begins to tell the story (the usual source of the headline);The original source of the story is given, either in byline or built into the text (A senior White House official said…);

The participants are categorized, their names usually being preceded by a general term (champ, prisoner, official) and adjectives (handsome French singer Jean Bruni…);

Explicit time and place locators are given (In Paris yesterday…), facts and figures (68 people were killed in a bomb blast…), and direct or indirect quotations (Pm ‘bungles’, says expert; Expert says PM bungled).

Слайд 53

Advertising English

can be observed in commercial advertising. It

uses:

deviant graphology (Beanz Meanz Heinz),

strong sound effects,

such as rhythm, alliteration, and rhyme. Commercial advertising provides fertile soil for adjective inflections, e.g. The result: smoother, firmer skin; The tastiest fish; The latest in gas cooking.

Advertisements rely a great deal on imperative sentences (Learn a language on location, stay with a welcoming local family, make friends with other visitors from around the world).

Слайд 54 Lexically, this variety of English tends to use

words which are:

vivid (new, bright),

concrete (soft, washable),

positive (safe, extra),

unreserved (best, perfect).

Advertising English is characterized by the use of:

highly figurative expressions, e.g. taste the sunshine in K-Y peaches (canned fresh).

word-play and is characterized by a wide use of slogans, e.g. Electrolux brings luxury to life; Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach.