- Главная

- Разное

- Бизнес и предпринимательство

- Образование

- Развлечения

- Государство

- Спорт

- Графика

- Культурология

- Еда и кулинария

- Лингвистика

- Религиоведение

- Черчение

- Физкультура

- ИЗО

- Психология

- Социология

- Английский язык

- Астрономия

- Алгебра

- Биология

- География

- Геометрия

- Детские презентации

- Информатика

- История

- Литература

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Музыка

- МХК

- Немецкий язык

- ОБЖ

- Обществознание

- Окружающий мир

- Педагогика

- Русский язык

- Технология

- Физика

- Философия

- Химия

- Шаблоны, картинки для презентаций

- Экология

- Экономика

- Юриспруденция

Что такое findslide.org?

FindSlide.org - это сайт презентаций, докладов, шаблонов в формате PowerPoint.

Обратная связь

Email: Нажмите что бы посмотреть

Презентация на тему New zealand

Содержание

- 2. Historical development. A distinct New Zealand

- 3. Pronunciation VowelsShort front vowelsIn New Zealand English

- 4. Like Australian and South African English, the

- 5. Conditioned mergers The vowels /ɪə/ as in near and /eə/ as in square are increasingly

- 6. Rhythm Rhythm has been important in determining

- 7. Usage New Zealanders will often reply to

- 8. Скачать презентацию

- 9. Похожие презентации

Historical development. A distinct New Zealand variant of the English language has been in existence since at least 1912, when Frank Arthur Swinnerton described it as a "carefully modulated murmur," though its history probably goes back further

Слайд 3

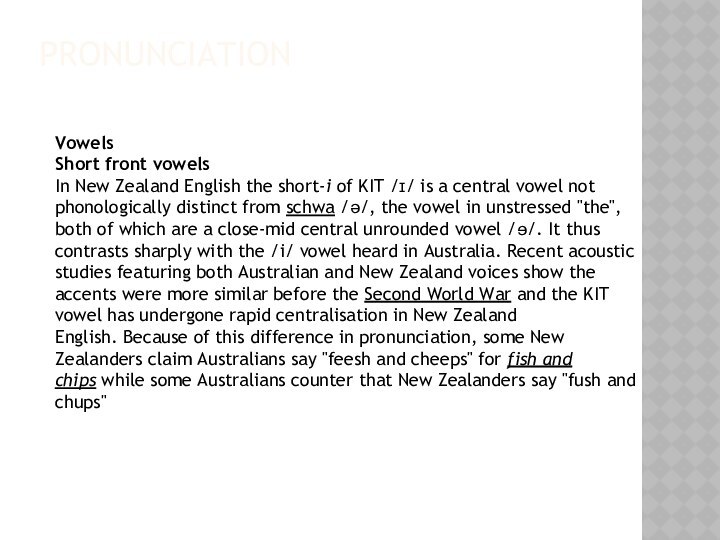

Pronunciation

Vowels

Short front vowels

In New Zealand English the short-i of

KIT /ɪ/ is a central vowel not phonologically distinct from schwa /ə/, the

vowel in unstressed "the", both of which are a close-mid central unrounded vowel /ɘ/. It thus contrasts sharply with the /i/ vowel heard in Australia. Recent acoustic studies featuring both Australian and New Zealand voices show the accents were more similar before the Second World War and the KIT vowel has undergone rapid centralisation in New Zealand English. Because of this difference in pronunciation, some New Zealanders claim Australians say "feesh and cheeps" for fish and chips while some Australians counter that New Zealanders say "fush and chups"Слайд 4 Like Australian and South African English, the short-e /ɛ/ of

YES has moved to become a close-mid vowel /e/, although

the New Zealand /e/ is moving closer to /ɪ/. This was played for laughs in the American TV series Flight of the Conchords, where the character Bret's name was often pronounced as "Brit," leading to confusion.The short-a /æ/ of TRAP is approximately /ɛ/, which sounds like the short-e of YES to other English speakers. The sentence "She is actually married to a happy man" said by a New Zealander is heard by other English speakers as "She is ectually merried to a heppy men." The only other English-speaking country that has a similar alteration of pronunciation for this vowel sound is South Africa but recently an increasing number of younger generations in New Zealand do not have this certain pronunciation. Thus many New Zealanders travelling abroad are often initially mistaken for South Africans, based on this vowel pronunciation alone. It is also the main reason why New Zealanders can be hard to understand to other English speakers, especially Americans and non-native English-speaking Europeans and Asians.

Слайд 5

Conditioned mergers

The vowels /ɪə/ as in near and /eə/ as in square are increasingly being merged,

so that here rhymes with there; and bear and beer, and rarely and really are homophones. This is

the "most obvious vowel change taking place" in New Zealand English. There is some debate as to the quality of the merged vowel, but the consensus appears to be that it is towards a close variant, [iə].Before /l/, the vowels /iː/:/ɪə/ (as in reel vs real), as well as /ɒ/:/oʊ/ (doll vs dole), and sometimes /ʊ/:/uː/ (pull vs pool), /ɛ/:/æ/ (Ellen as Alan) and /ʊ/:/ɪ/ (full vs fill) may be merged

Слайд 6

Rhythm

Rhythm has been important in determining the existence

of the dialect of Maori English. Bauer for instance,

observed in 1995 that Maori English is more syllable-timed—the rhythm units are syllables—than other forms of NZE, though NZE in general is more syllable-timed. Maori school children were found by Benton to use a full vowel rather than a reduced vowel, creating what he described as “a jerky rhythm.” Essentially, “the unstressed syllables are not skipped over as is normal in English Speech” .On “home gardens,” for example, the children would place the primary stress on secondarily stressed syllables. One possible explanation for this can be found by examining Te Reo Maori, which has been acknowledged as a mora-timed language, a mora being a unit of time similar to a short syllable. Consequently, it “might be expected to exhibit a timing pattern that is more like syllable—than stress-timing, with less variation in syllable length.

Слайд 7

Usage

New Zealanders will often reply to a question

with a statement spoken with a rising intonation at the end.

This often has the effect of making their statement sound like another question. There is enough awareness of this that it is seen in exaggerated form in comedy parody of New Zealanders. This rising intonation can also be heard at the end of statements, which are not in response to a question but to which the speaker wishes to add emphasis. High rising terminals are also heard in Australia and are more common.In informal speech, some New Zealanders use the third person feminine she in place of the third person neuter it as the subject of a sentence, especially when the subject is the first word of the sentence. The most common use of this is in the phrase "She'll be right" meaning either "It will be okay" or "It is close enough to what is required". This is similar to Australian English.