Слайд 2

Introduction

Aim of the lecture: explore how (pre-game) communication

and information manipulation may alter the outcome of the

game.

“Cheap talk”: Direct costless communication between players where by players announce which actions they will take.

Signaling/screening: In game of incomplete information, agents may manipulate information by taking certain actions.

Слайд 3

Communication: Perfectly aligned interests

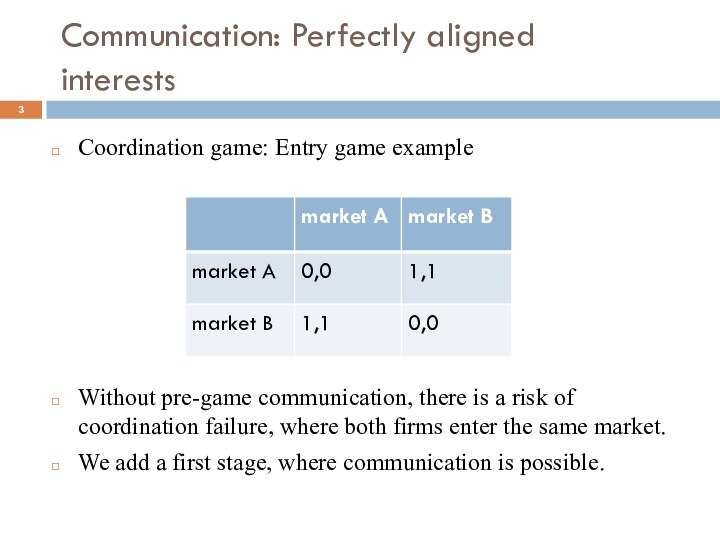

Coordination game: Entry game example

Without

pre-game communication, there is a risk of coordination failure,

where both firms enter the same market.

We add a first stage, where communication is possible.

Слайд 4

Communication: Perfectly aligned interests

Suppose Firm 1 can announce

at no cost its choice of action before Firm

2 gets to choose. The announcement is nonbinding, “cheap talk.”

“I will enter market A”

If Firm 2 believes Firm 1, it will choose B.

By sending a truthful message, Firm 1 can prevent coordination failure.

Firm 1 will be truthful, and Firm 2 has no reason not to believe Firm 1.

Coordination can be easily achieved. Pre-game communication benefits both players.

Слайд 5

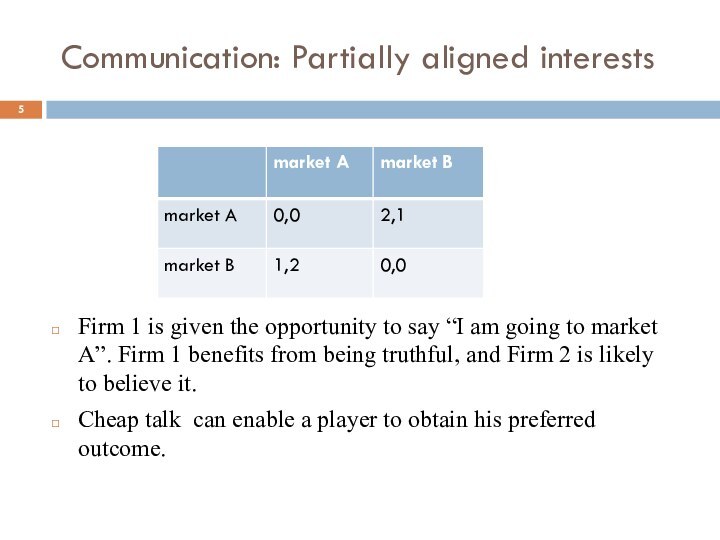

Communication: Partially aligned interests

Firm 1 is given the

opportunity to say “I am going to market A”.

Firm 1 benefits from being truthful, and Firm 2 is likely to believe it.

Cheap talk can enable a player to obtain his preferred outcome.

Слайд 6

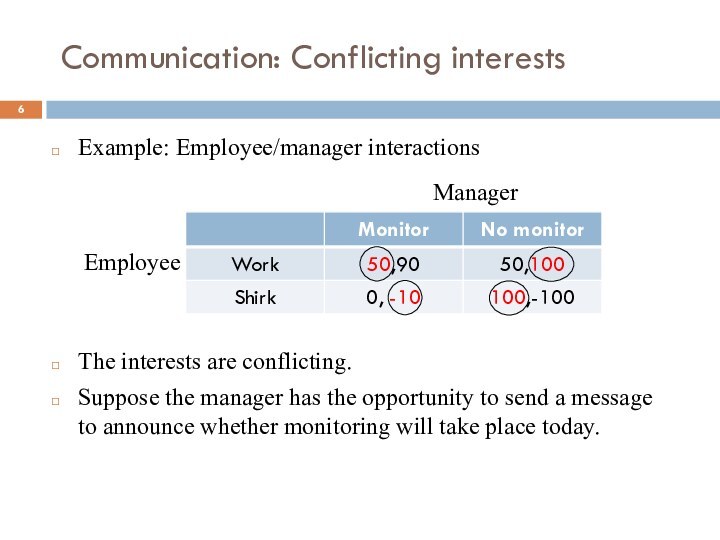

Communication: Conflicting interests

Example: Employee/manager interactions

The interests are conflicting.

Suppose

the manager has the opportunity to send a message

to announce whether monitoring will take place today.

Manager

Employee

Слайд 7

Communication: Conflicting interests

If the manager says “I will

monitor today”, then the employee will choose “Work” if

he believes the manager.

But then, the manager has no incentive to actually monitor, and is better off doing the opposite of what the signal said. The signal is not truthful.

But if the manager always does the opposite of what he says, the employee will choose to shirk. Knowing this, the manager will monitor…etc.

The employee should just disregard the signal. When players have conflicting interests, pre-game communication is uninformative. (babbling equilibrium)

Слайд 8

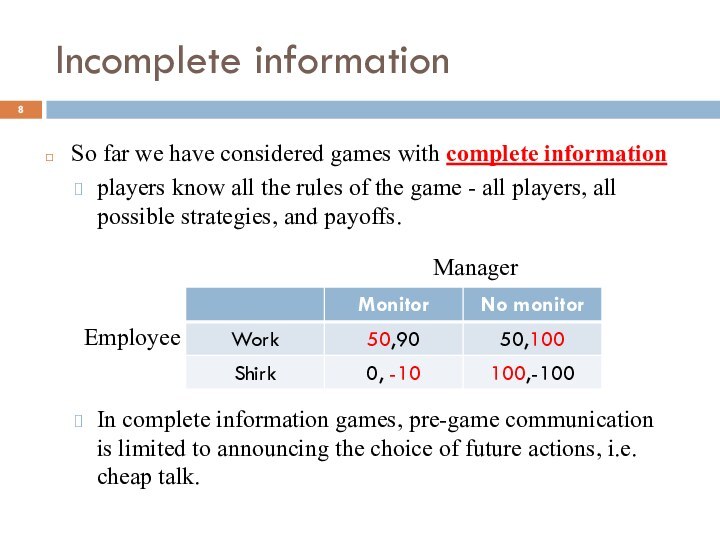

Incomplete information

So far we have considered games with

complete information

players know all the rules of the

game - all players, all possible strategies, and payoffs.

In complete information games, pre-game communication is limited to announcing the choice of future actions, i.e. cheap talk.

Manager

Employee

Слайд 9

Incomplete information

In incomplete information games, players may not

have some information about the other players, e.g. about

their type and payoffs.

Producers may not know each others’ costs functions.

An entrant may not know how costly if would be for the incumbent to fight a new entrant.

In a bargaining games, parties may not know each other’s degree of impatience and outside option.

Players know more about themselves than about other players.

Слайд 10

Incomplete information

Possessing superior information is often an advantage,

and allows greater flexibility to adjust to the other

player’s profile

Bargaining game: The optimal offer depends on the other player’s degree of impatience and outside option.

Entry game: the entrant may want to know how tough the incumbent is; the incumbent may want to know how committed the entrant is.

Слайд 11

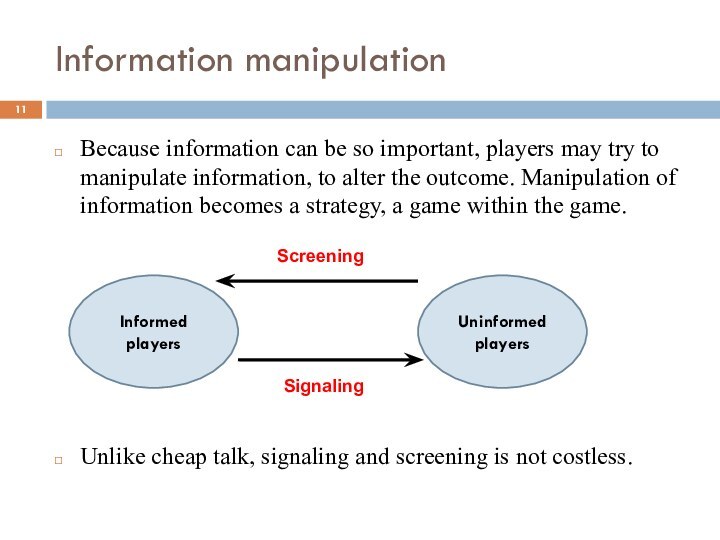

Information manipulation

Because information can be so important, players

may try to manipulate information, to alter the outcome.

Manipulation of information becomes a strategy, a game within the game.

Unlike cheap talk, signaling and screening is not costless.

Informed players

Uninformed players

Screening

Signaling

Слайд 12

Signaling: The better-informed attempts to signal something about

his type.

Reveal information truthfully, e.g. reveal that you are

patient in a bargaining game.

Reveal misleading information, e.g. hide the fact that you are impatient.

Screening: The less-informed player tries to elicit information and filter truth from falsehood

Employer wants to find out how hard-working its employees are.

Consumers wish to learn if a seller is trustable or not.

Signaling/screening

Слайд 13

Adverse selection and signaling:

the lemon problem

Market for

second-hand cars:

Two types of cars.

Good cars: valued at

$12,500 by the seller

Bad cars: valued at $3,000 by the seller

The potential buyer is willing to pay:

$16,000 for a good car

$6,000 for a bad car (the lemon)

Depending on bargaining power of the two players, the price of the good car will between $12,500 and $16,000. The price of the bad car between $3,000 and $6,000.

Слайд 14

The lemon problem: Asymmetric information

Information is asymmetric: Sellers

know the value of the car, but buyers don’t.

Sellers

of good car would like to indicate that their cars are good, but so do sellers of bad cars. Direct communication is not credible, and buyers remain uninformed.

When quality is unobservable, there can only be one price p for both types of cars.

Слайд 15

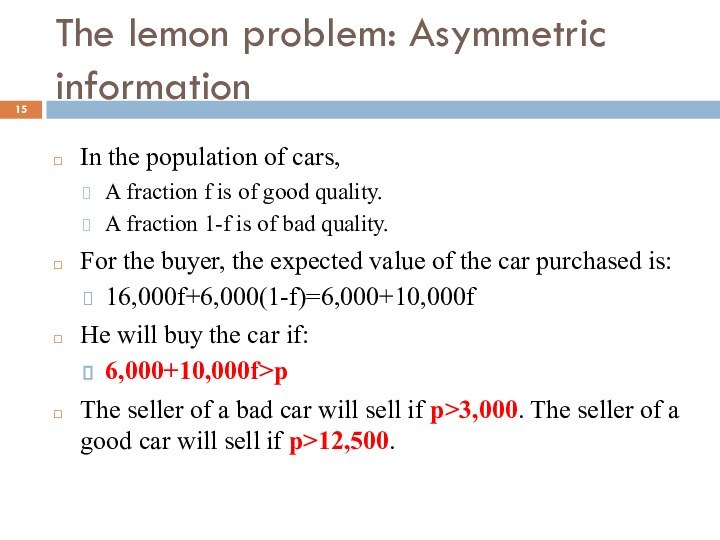

The lemon problem: Asymmetric information

In the population of

cars,

A fraction f is of good quality.

A fraction 1-f

is of bad quality.

For the buyer, the expected value of the car purchased is:

16,000f+6,000(1-f)=6,000+10,000f

He will buy the car if:

6,000+10,000f>p

The seller of a bad car will sell if p>3,000. The seller of a good car will sell if p>12,500.

Слайд 16

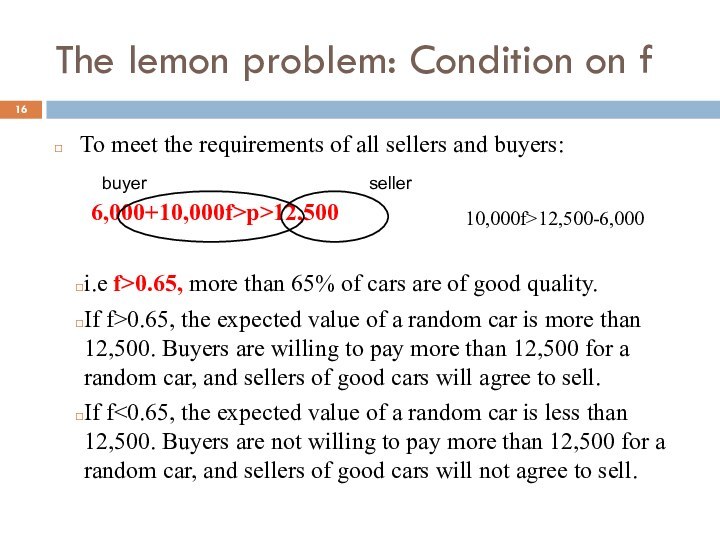

The lemon problem: Condition on f

To meet the

requirements of all sellers and buyers:

6,000+10,000f>p>12,500

i.e f>0.65, more than

65% of cars are of good quality.

If f>0.65, the expected value of a random car is more than 12,500. Buyers are willing to pay more than 12,500 for a random car, and sellers of good cars will agree to sell.

If f<0.65, the expected value of a random car is less than 12,500. Buyers are not willing to pay more than 12,500 for a random car, and sellers of good cars will not agree to sell.

buyer

seller

10,000f>12,500-6,000

Слайд 17

The lemon problem: adverse selection

When f

an adverse selection problem. Sellers of good cars will

drop out, and only low quality cars will remain on the market.

Potential buyers will recognize this, and pay at most 6,000. Bad cars drive the good cars out.

More generally, because of asymmetric information, producers of high quality products may not expect proper profit, so will not participate in the market.

Слайд 18

Solving adverse selection: warranties

Adverse selection originates from information

asymmetry. Cheap talk is not going to work. Sellers

of high quality cars may signal high quality using warranties.

If the product is faulty of damaged, the seller will replace it.

Suppose that buyers perceive any car with a warranty to be of good quality, and any car without a warranty to be of bad quality.

Suppose that:

For sellers of good cars, the cost of offering warranties is $0. Good cars never fail.

For sellers of bad cars, the cost of offering warranties is $11,000. Low quality cars are more likely to fail.

Слайд 19

Solving adverse selection: warranties

Sellers of good cars will

choose to offer a warranty:

Costs $0.

With warranty they can

sell the car for $16,000, without warranty they can sell it for $6,000.

Sellers of bad cars will choose not to offer a warranty:

Costs $11,000.

With warranty they can sell the car for $16,000, without warranty they can sell it for $6,000. (difference of $10,000)

Слайд 20

Solving adverse selection: warranties

Sellers of good cars can

use warranties to credibly signal the quality of the

car. ? Signaling

Signaling works because good quality producers provide warranties which low quality producers cannot imitate.

Warranties act as a “separating mechanism”. Whether warranty is offered depends on the quality of the car.

Слайд 21

Solving adverse selection: advertising

Sellers of high-quality products advertise

to signal the quality of their products.

For advertising

to be worthwhile, consumers must buy the product repeatedly.

Low-quality sellers do not find it worthwhile to advertise

High-quality sellers find it worthwhile to advertise

It is not the advertising message itself that is effective in convincing consumers. Rather, the simple fact of advertising signals that the product must be of high quality.

Слайд 22

Solving adverse selection:

value of the brand

Over the

long-term, high-quality sellers may be able to acquire a

strong reputation and increase the value of their brand.

Once reputation has been established, adverse selection is less of an issue, and the signaling motive for warranties and advertising may be less important.

Over the long-term, the brand itself may act as a signal.

Слайд 23

Signaling in the labor market:

Spence education model

What credible

signal can be used to convince

employers that

you are highly skilled and they should

hire you?

Spence argues that attending university, and taking tough courses can be used to signal skills.

Consider an employer and two types of potential workers (students):

Able (A), Challenged (C).

Employers are willing to pay $160k for A type and $60k for a C type. The student’s type is not observable to the employer.

Слайд 24

Spence education model

Setting

What each player tries to achieve:

Employer:

find out students’ types.

Able students want to separate themselves

from the challenged.

Challenged students want to mimic able students.

Cheap talk is not credible, all students will claim to be able.

Able students may use signaling strategies

Слайд 25

Spence education model

Setting

Key assumption: Able students are

more

willing to take difficult courses

than challenged students

For

A-type: cost of each tough course is $3,000 (low risk of failing the course)

For C-type: cost of each tough course is $15,000

Слайд 26

Spence education model

Hiring policy

Consider the following employer’s policy:

Any student taking more than n tough courses is

paid $160,000.

Any student taking less than n tough courses is paid $60,000.

Assumption of the employer:

Any student taking at least n tough courses is assumed to be type A.

Any student taking less than n tough courses is assumed to be type C.

Can this assumption be justified?

Слайд 27

Spence education model

Hiring policy

A-type will try to take

many tough courses to signal their ability, but so

will C-type. However, taking courses is more costly for C-type.

The employer assumption that only A-type will select to take n course may be correct if it is too costly for C-type to take n tough courses.

Слайд 28

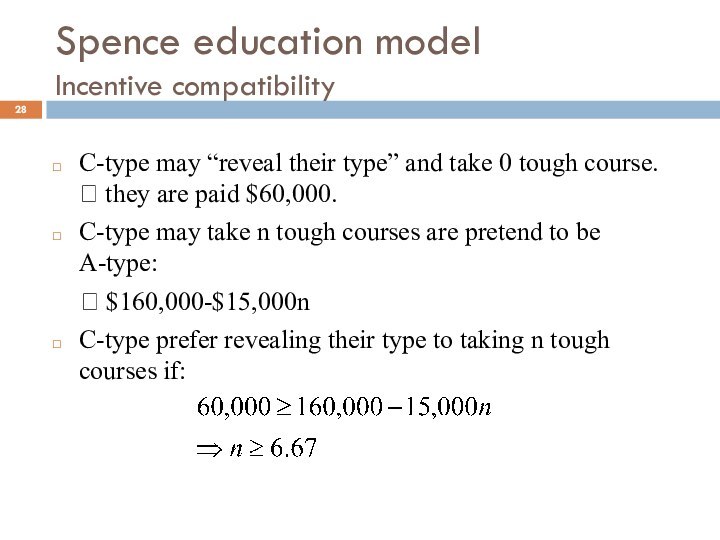

Spence education model

Incentive compatibility

C-type may “reveal their type”

and take 0 tough course. ? they are paid

$60,000.

C-type may take n tough courses are pretend to be A-type:

? $160,000-$15,000n

C-type prefer revealing their type to taking n tough courses if:

Слайд 29

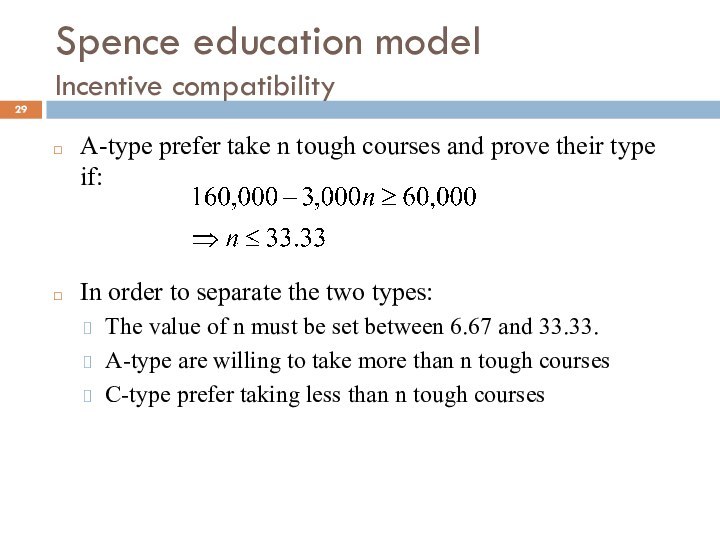

Spence education model

Incentive compatibility

A-type prefer take n tough

courses and prove their type if:

In order to separate

the two types:

The value of n must be set between 6.67 and 33.33.

A-type are willing to take more than n tough courses

C-type prefer taking less than n tough courses

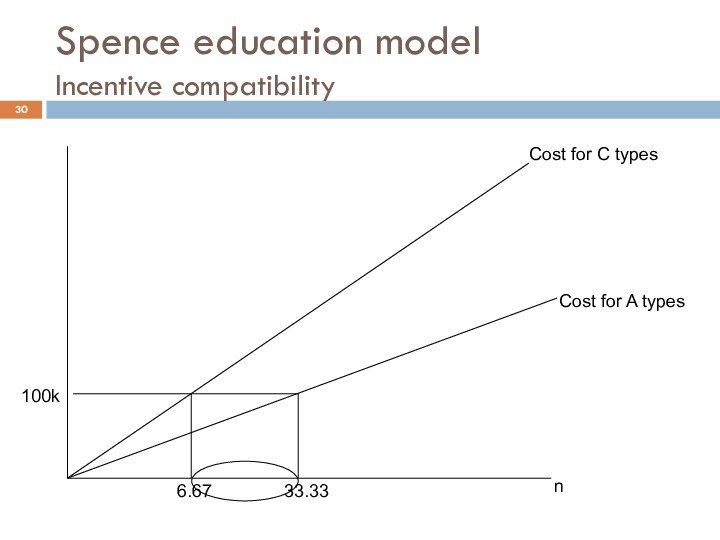

Слайд 30

Spence education model

Incentive compatibility

100k

Cost for A types

Cost for

C types

6.67

33.33

n

Слайд 31

Spence education model

Payoffs

Employers can set n=7.

A types choose

n=7

C types choose n=0

Intuition:

A-type can signal they type

and separate themselves from C-type because the cost of tough courses is low to them.

C-type reveal their true types, because this is better than taking too many tough courses.

Payoff for A= 160,000-7*3,000= $139,000

Payoff for C= $60,000

Слайд 32

Spence education model

Implications

A positive relationship between years of

education and wages does not necessarily show that education

improve skills.

Instead, education can act as a screening device used to identify the ability of job candidates.

Go to university to signal your ability, go to the best universities to send an even stronger signal on your ability.